The Mormons in Missouri

1831–1838

Joseph Smith (1805-1844) published the Book of Mormon in 1830, while he was living in Palmyra, New York. As he shared his revelation, and converts began to increase, Smith sent a small group of people to Missouri to prepare a place for the Mormons (as they were commonly known) to gather because Smith believed that there he and his followers would found the New Jerusalem and Christ would return to earth. The first Mormon arrivals began building a community in Jackson County, near present-day Independence.

Photo by W. B. Carson of a portrait of Joseph Smith by an unknown artist (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

As the number of Mormons in Jackson County increased, so did tensions with other settlers in the area. Some of this had to do with religious differences – to traditional Christians Mormons appeared an odd, if not heretical, cult – but much of it had to do with the fact that Mormons tended to vote as a bloc. As their numbers increased, they could exert political power through the ballot box – or such was the fear of the other settlers. The group cohesion of the Mormons was also thought to give them unfair economic advantages. Another factor leading to anti-Mormon sentiment were Mormon efforts to convert native Americans in the area, whom the Book of Mormon claimed were descendants of the lost tribe of Israelites. Finally, most Mormons had come from areas where abolitionism was strong and carried these sympathies to Missouri, which had strong pro-slavery advocates in its population. (In fact, although African-Americans were members of the Mormon church, the church was not actively abolitionist.)

These social tensions escalated to phsyical conflict, and eventually mob action that drove the Mormons out of Jackson County and into Clay County, the adjacent county to the north, in 1833. Yet conflict continued in Clay County. In an effort to devise a settlement, the state legislature passed a law in 1836 creating Caldwell County, to the northeast of Clay County, as a place for Mormon settlement. The Mormons established the town of Far West in Caldwell County as their principal location. Joseph Smith moved to Far West in 1838, after fleeing financial problems and church strife in Kirtland, Ohio, where the he had moved after leaving Palmyra.

The establishment of Caldwell County and Far West did not address the causes of the antagonism between the Mormons and other settlers in Missouri. Nor did Mormons feel that it had fully compensated them for the land and other property they had lost when they were forced out of Jackson County. As more Mormons arrived in Missouri, they settled in counties adjacent to Caldwell. The tensions and conflicts returned. Feeling beleaguered, the Mormons spoke openly of self-defense and organized to provide it. On July 4, 1838, Sidney Rigdon, one of Smith’s lieutenants and often his spokesman, who had come to Missouri with Smith, gave a speech in which he threatened “a war of extermination” between the Mormons and those who attacked them. This speech and Mormon efforts at self-defense made the Missourians more fearful of the growing Mormon presence.

In 1838, the conflicts erupted into what is often called the “Mormon War,” a series of mob actions and skirmishes that took place from August through the end of the year. The “war” began at an election site in August, when a mob prevented Mormons from voting. Action and counter-action by Mormons and groups of vigilantes resulted in several “battles,” but mostly in sieges of Mormon towns and burning of Mormon homesteads. In October, the Governor of Missouri, Lilburn Boggs, issued an order declaring the Mormons in defiance of the law and, perhaps in response to Rigdon’s speech, that “the Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary for the public peace.” Under the pressure of attacks, Mormons fled to Far West, where the fighting culminated in the siege of the city. Eventually, Smith decided to surrender and to accept that the Mormons would have to leave Missouri. They were given a few months in which to do so. Much of their property was destroyed or taken as compensation for the costs of suppressing what the state of Missouri considered their rebellion.

Smith and his followers left Missouri for Illinois in the spring of 1839.

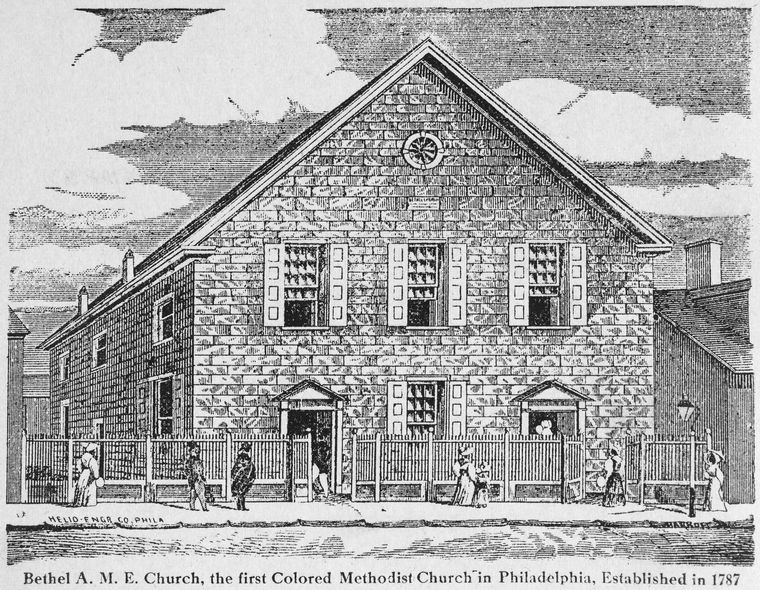

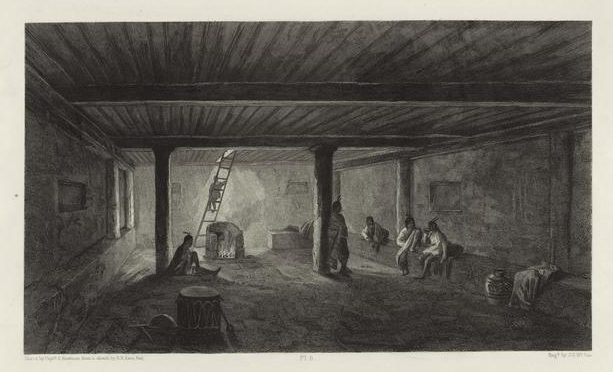

The print shop where Newell Whiney worked

It is worth considering the Mormon experience in light of Lincoln’s Address to the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield, Illinois, in which Lincoln spoke of the “mobocratic” spirit at large in the country and the danger that posed to American democracy. Lincoln gave the speech in January 1838, a few months before the events that drove the Mormons from Missouri.

The press Whiney used

Given the fighting and destruction, little remains of the Mormon presence in Missouri. In the recent past the Mormon church, now headquartered in Salt Lake City, has established a visitor’s center in Independence near the site where Smith believed that the Lord would return. The visitor center includes some dioramas depicting how Mormons lived during the 1830s in Missouri. The pictures at the right show the re-created print shop where Newell Whitney, a prominent early Mormon, worked.

In nearby Liberty, Missouri, the church has another Visitor Center at the site of the Liberty jail, where Smith and some of his companions were held following his surrender at Far West. The group escaped or were allowed to escape in April 1839, when they headed to Illinois, where other Mormons had moved.

The Community of Christ Temple in Independence, Missouri

Across the street from the Visitor Center is a temple of the Community of Christ, with a distinctive spiraling roof. The Community of Christ is a Mormon church separate from the Church of Latter Day Saints now headquartered in Salt Lake City. (Smith adopted the name Church of Latter Day Saints in 1838.) The split originated in disagreements about who was Smith’s legitimate successor, although the Community of Christ has over the decades developed doctrines that distinguish it from other Mormon churches. The Community of Christ also owns the temple in Kirtland, Ohio.