Mother Bethel A. M. E. Church

July 29, 1794

Mother Bethel, one of the first African-American churches in the United States, was dedicated July 29, 1794, by Methodist Bishop Francis Asbury. In 1816, it became the site of the new African Methodist Episcopal Church denomination.

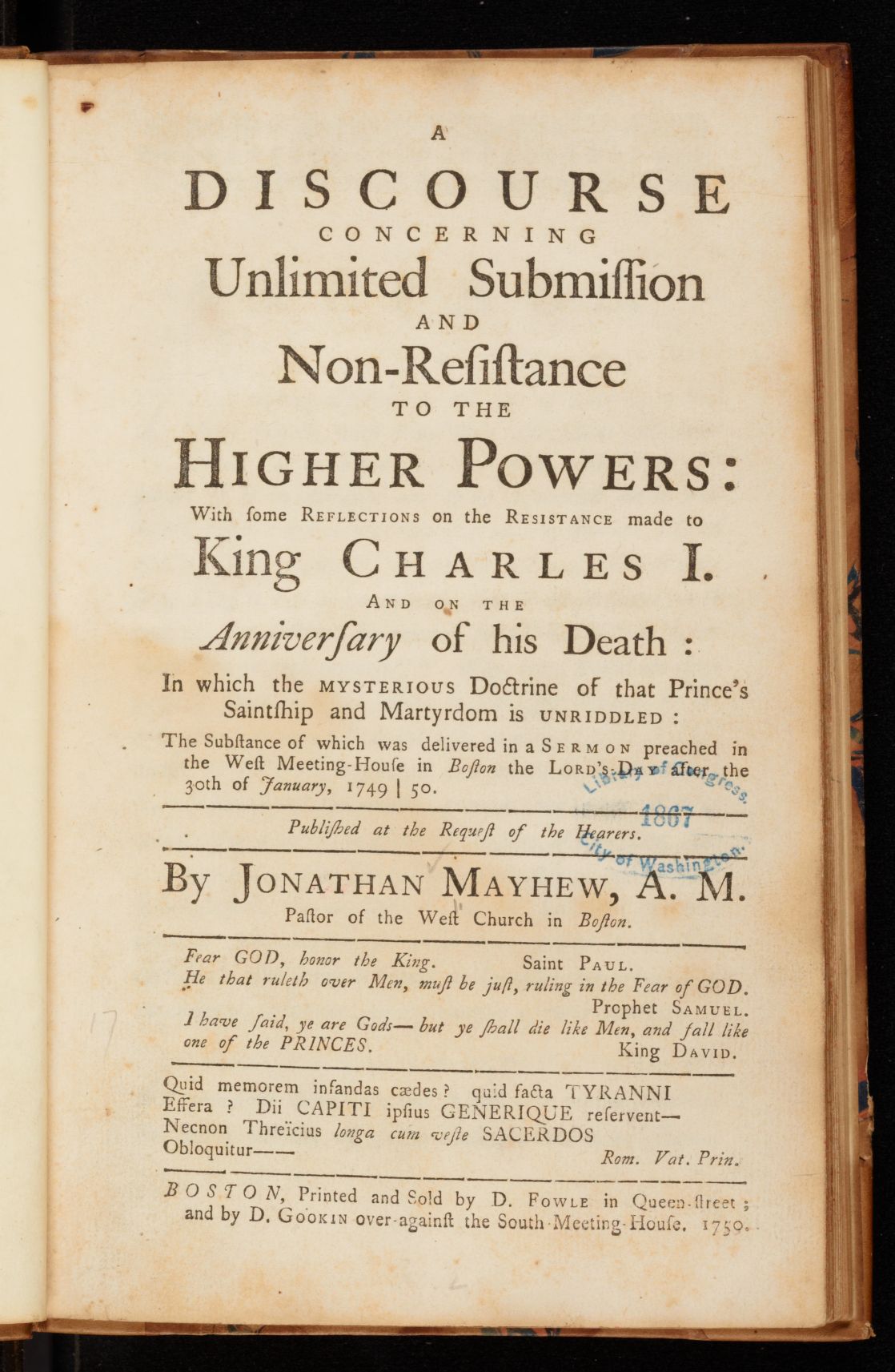

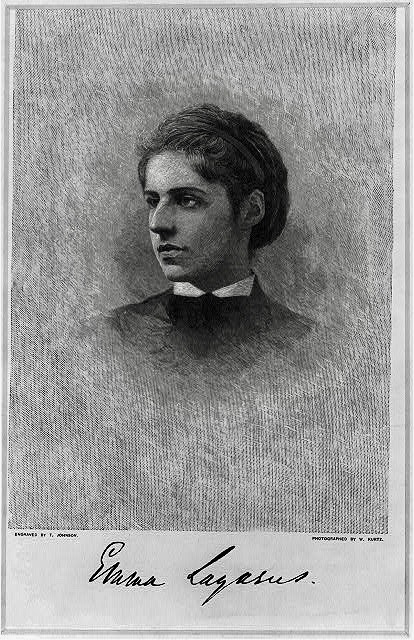

The Revd. Richard Allen, Bishop of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church in the U. States. Stipple engraving by John Boyd, after the oil painting by Rembrandt Peale (Philadelphia, 1823). Courtesy of the Library Company, https://librarycompany.org/.

Born into slavery in 1760, Richard Allen was converted by the preaching of an itinerant Methodist minister as a young man. He quickly became known for his eloquent and powerful ability to convey gospel truths in both word and deed. He also exhibited a strategic sense that served him well throughout a life dedicated to racial equality and racial reconciliation.

After their conversion, Allen and his brother resolved to serve the man who enslaved them more faithfully than ever, so as to prevent the white community from concluding that sharing the gospel message with the enslaved would make them rebellious. Yet at the same time, he resolved to use the help of Methodist evangelists to achieve his own freedom. He asked the man who held him in slavery to permit traveling preachers to speak in his home to his family and servants. The owner was eventually convinced of the peril to his own soul if he continued holding slaves. He allowed Allen to do extra work in order to purchase his freedom. By cutting wood after dark for neighboring farms, Allen bought his freedom in less than four years.

Allen then became an itinerant on the Methodist circuit, traveling in the upper South and the mid-Atlantic regions. He preached to both white and black congregations, taking on odd jobs to earn enough to pay his own way when hospitality in a town was lacking. In 1786, Allen settled in Philadelphia, after being invited to preach to the black members of the congregation at St. George’s Methodist Church in Philadelphia. Although the Methodist denomination wanted to evangelize among African Americans, many Methodists did not welcome racially integrated services. They asked Allen to preach at 5 am. He soon attracted a growing group of black congregants who wished to worship at the more conveniently scheduled services whites attended. Church leaders seated them in the balcony. Sometime in the early 1790s, Allen and his colleague in ministry, Absalom Jones, challenged the segregation, moving to pews on the main floor. After a trustee of the church tried to evict them during prayer, Jones and Allen led black members in a dramatic walk-out, never to return. Then Allen set about building a church where African Americans could worship together without supervision from Methodist authorities.

He received help from physician and social reformer Benjamin Rush, among others, in raising the money necessary. He bought a plot of land on Sixth and Lombard Streets in Philadelphia. Building took several years; but in November 1794, the new church was dedicated. Francis Asbury, the presiding Bishop of the Methodist Church in America, who had encouraged Allen since his days of itinerant preaching, gave the dedicatory sermon. Allen named the new congregation the African Methodist Episcopal Church, soon calling it the “Bethel AME Church”–a temple welcoming all. Asbury returned to the Bethel church in 1799 to formally ordain Allen as a minister.

In the summer of 1793, before the church building was complete, yellow fever broke out in Philadelphia. Rush, mistakenly believing that African Americans carried an immunity to the disease, appealed to Allen and Jones to organize a team of black volunteers to nurse those who fell ill. Jones and Allen agreed, hoping to demonstrate dedication to public welfare in what was then the nation’s capital city. Volunteers visited the sick in their homes, performed the bleeding therapy Rush prescribed, sat with the dying, and buried the dead, requesting only minimal payment. Allen himself fell ill during this time; both he and Jones incurred expenses that were never repaid them, since the epidemic was costly to the community as a whole.

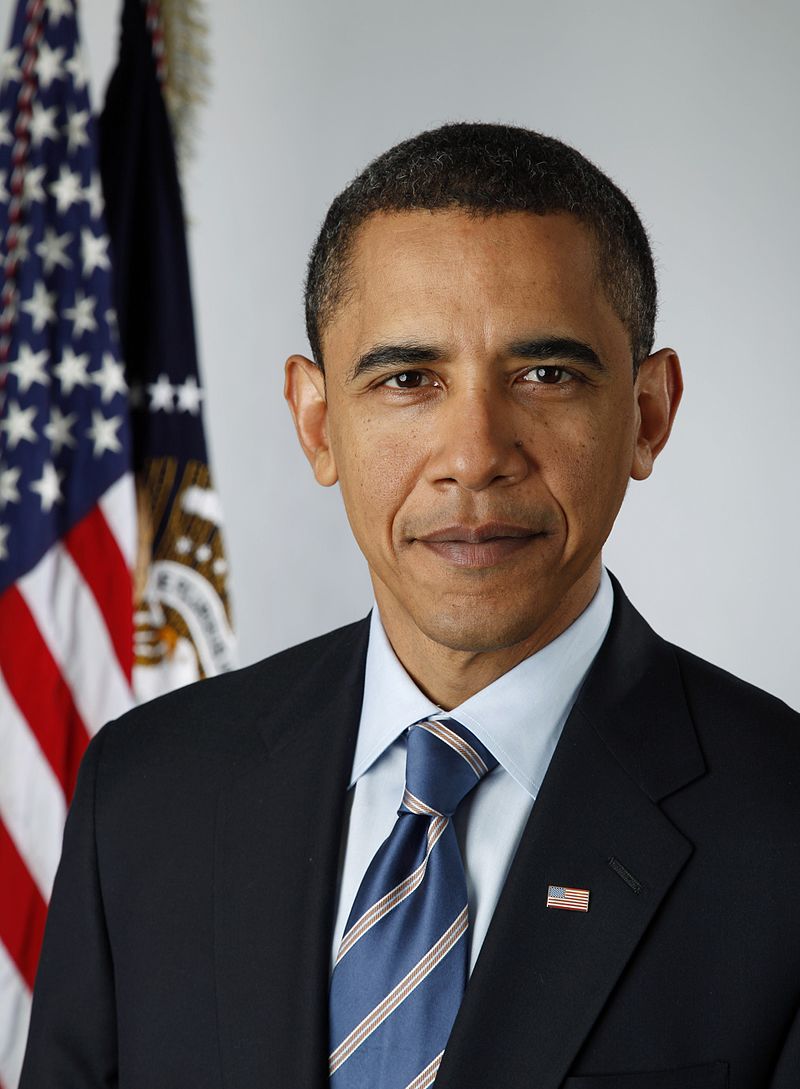

Detail of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Lithograph by W. L. Breton (Philadelphia, 1829). Courtesy of the Library Company, https://librarycompany.org/.

Allen secured corporate status for Bethel Church through an application to the state of Pennsylvania in 1796. But this process required him to accept the technical authority of the Methodist Church over his congregation. It took 20 more years of legal wrangling to establish the congregation’s independent ownership of their church property. Finally, in 1816, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Mother Bethel congregation. Allen and other African Americans who had founded black Methodist congregations in the mid-Atlantic region then officially organized the African Methodist Episcopal denomination, with Allen becoming its first Bishop.

Original Bethel A.M.E. Building, as pictured in the 1910 Philadelphia Colored Directory. Courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-9d9d-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Throughout his life, Allen preached a gospel of freedom and equality, urging Americans to recognize that their shared Christianity mattered more than the different shades of their skin. He was vehemently opposed to all proposals for African Colonization. Although he initially discouraged women from preaching to mixed audiences of men and women, he was always a strong advocate for the spiritual equality of women. After hearing Jarena Lee preach extemporaneously in 1819, however, he changed his mind and supported her ministry as an itinerant preacher of the gospel along the eastern seaboard.

“Mother” Bethel A.M.E. Church, as it is now known, is the oldest church property in the United States to have been continuously owned by African Americans. A National Historic Landmark, it remains a vibrant center of worship in Philadelphia.

Citation

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES

INVENTORY – NOMINATION FORM, available online https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NHLS/72001166_text

Richard S. Newman, Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers. New York University Press, 2008.