Carmel Mission Basilica

1771-Present

Carmel Mission Basilica. Photo by Carol Highsmith, from the Jon B. Lovelace Collection of California Photographs, Library of Congress.

The Franciscan mission in Carmel, California largely failed to make Catholic converts of the native population, but it did help to shape the European settlement of California, selecting the sites that would later become cities, introducing an agricultural and ranching economy, and imprinting the state with aspects of Roman Catholic culture that later migrants from Latin America would find familiar and welcoming.

Establishment of the California Missions

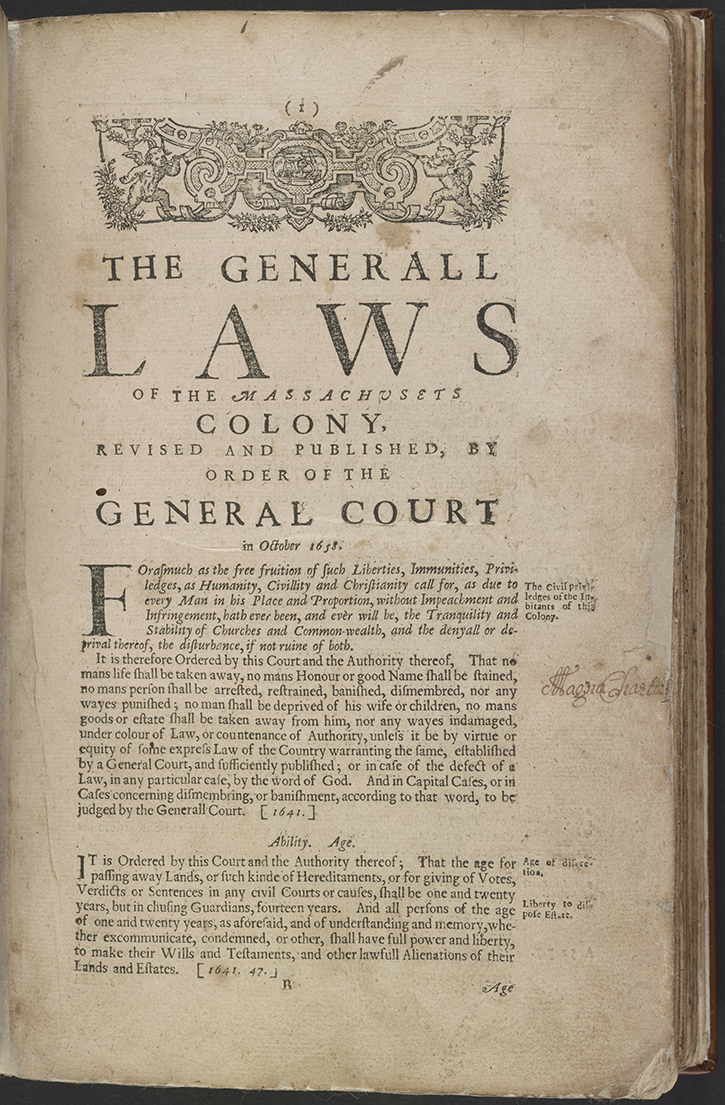

Beginning in 1542, explorers commissioned by the Spanish crown sailed from present-day Mexico up the California coast, searching for harbors and establishing a foothold so as to claim the Pacific coast of North America for Spain. Serious colonization efforts did not begin until the late 17th century, however, when Jesuit priests began organizing missions along the coast. In 1767, the Spanish king expelled the Jesuit order from all his provinces and directed the Franciscans (who had encouraged questions about the Jesuits) to establish missions in their place.

Mission San Diego De Alcala in 1904. This was the first mission established in Alta California by the Franciscans.

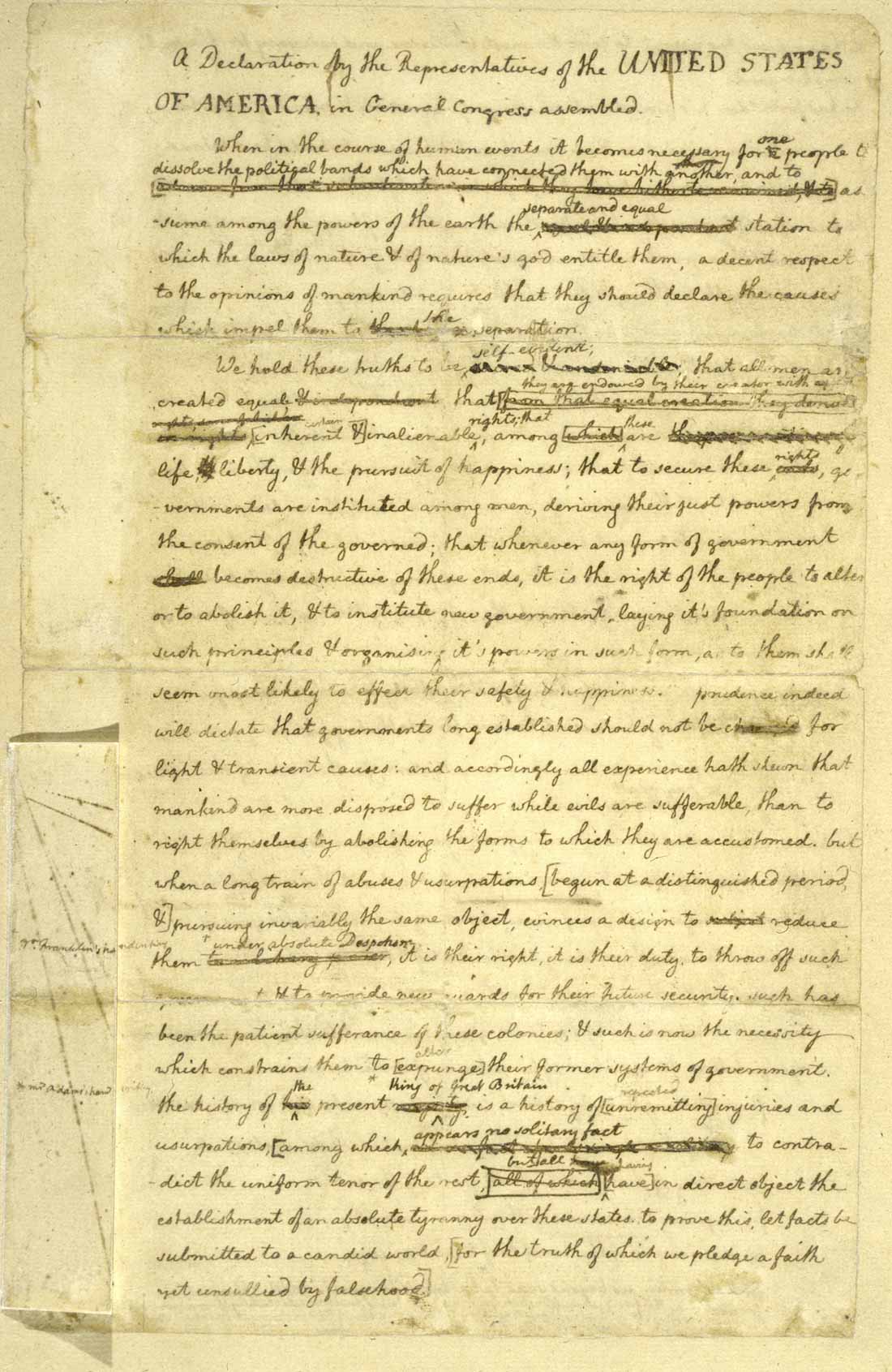

Father Junipero Serra was appointed to head this effort. He and other priests founded the first mission at present-day San Diego in 1769. They founded the second near the already-existing Presidio, or fort, on Monterey Bay in 1770, a year later moving the mission a few miles south to a site near the mouth of the Carmel River, since Serra deemed this location more suitable for farming. He also wanted to separate the mission community from the rough soldiers at the presidio, who threatened the women among the Native Americans Serra was converting to Christianity and organizing as a labor force for the mission settlement. Yet with the nearby Presidio becoming the capitol of Alta California, the Carmel mission became Serra’s headquarters, from which he and his successors supervised the establishment of 19 more missions on the California coast. They also blazed an overland north-south trail between the mission outposts, El Camino Real, that ran close to the route followed by Highway 101 today.

Impact on the Native American Population

Native Americans working at the Spanish Missions

Since those claiming Alta California for Spain were military men and priests—they did not bring ordinary Spanish settlers with them—the mission system depended on Native American labor. Under Franciscan leadership, native tribes were conscripted to live at the mission sites and generally kept against their will. They grew crops to feed the mission population, tended sheep and cattle, and eventually built handsome adobe structures housing sanctuaries, gardens and living spaces. The intent was to make true converts who would intermarry with the Spanish soldiers and later settlers, helping them build a new world culture modeled on that of Spain. Some natives did embrace the new faith, and some contributed their own artistry to the building effort; in recent years Native American wall paintings have been found underneath layers of plaster inside some mission buildings. But the regimented labor the priests required was largely foreign to Native American customs. John Steinbeck satirically depicted the relations between the Spanish and the natives—Ohlone and Esselen tribes in the Monterey region—in the opening chapter of his 1933 short story collection Pastures of Heaven, set in Carmel Valley:

When the Carmelo Mission of Alta California was being built . . . a group of twenty converted Indians abandoned religion during a night, and in the morning were gone from their huts. Besides being a bad precedent, this minor schism crippled the work in the clay pits where the adobe bricks were being molded.

After a short council of the religious and civil authorities, a Spanish corporal with a squad of horsemen set out to restore these erring children to the bosom of Mother Church. . . . It was a week before the soldiery found them, but they were discovered at last practicing abominations in the bottom of a ferny canyon in which a stream flowed; that is, the twenty heretics were fast asleep in attitudes of abandon. . . .[1]

Photo by C.W.J. Johnson of Mission San Carlos Borromea (the Carmel Mission) in about 1870. From the Historic American Buildings Survey, Ed Grabhorn’s Collection, Library of Congress.

It should also be noted that the mission system in Alta California reflected the land ownership system that developed in the southern Iberian peninsula after the Spanish reconquest in 1492 of territory that for several centuries had been under North African Muslim rule. The officers who fought in the reconquest were given titles to large estates, becoming feudal landlords, and their non-inheriting younger sons, becoming soldiers, would sail for the Americas in hopes of becoming landowners there. The servitude that the Spanish intended to impose on the Native Americans did not differ greatly from that of the Spanish peasantry. The effects on the Native Americans were more dire, however, because they were not inured to the hard labor habitual among the peasants and had no immunity to the Eurasian diseases that the Spanish brought with them.

Decline of the Mission System

Alta California became a part of the newly independent nation of Mexico in 1821, and in 1834 the Mexican republic secularized the California missions. In theory, secularization meant that the mission lands would be divided between the church and the native population. But much of it was distributed in land grants to the Mexican elite, and that portion the Native Americans received soon fell into the hands of speculators. Since the priests were unable to maintain the remaining mission property without native labor, they abandoned it and buildings such as the Carmel Mission fell into ruin.

Sanctuary of the Carmel Mission photographed in the 1860s, before its restoration, Historic American Buildings Survey From California State Library Sacramento, rephotographed in the 1940s, Library of Congress.

Legacy and Historical Remembrance

After California became the 31st state in the union in 1850, the Federal Land Commission reviewed the mission properties and set in motion acts of Congress and court actions that by the end of the 1860s had returned most to the Catholic Church. The Carmel Mission was returned to Franciscan control in 1863 and some restoration work began then. Most of the restoration work did not begin until the 1930s, at a time when the mission was put under control of the local diocese.

Supervised by Harry Downie, the restoration eventually recreated much of the original the Carmel Mission interior and exterior architecture. The mission was designated a minor basilica by Pope John XXIII in 1960. Junipero Serra’s canonization by Pope Francis in 2015 occasioned a Papal visit attended by both celebration and controversy, given increasing historical awareness of the hardships inflicted on the native population during the mission-building effort.

Sanctuary of the Carmel Mission today

[1] Pastures of Heaven, ed. James Nagel (Penguin Books, 1995), p. 3.