Taos, New Mexico

1680

The Pueblo Revolt

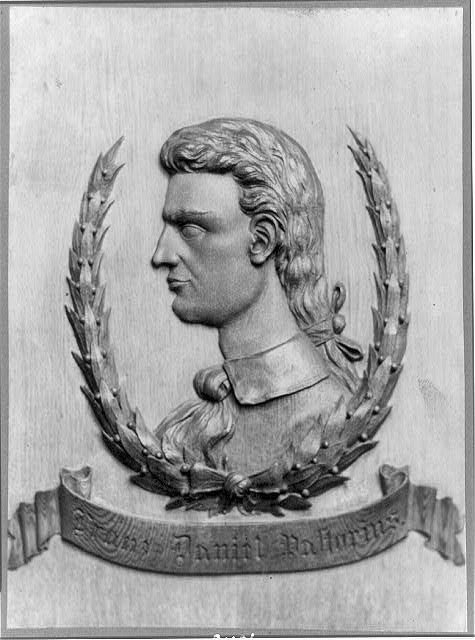

1893 | Charles Barbant. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed September 19, 2016. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-1be3-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2005 | Cliff Fragua. Architect of the Capitol. Note the knotted cords in Po’Pay’s hands.

On August 11, 1680, after eighty years of Spanish domination, the settled native population of the Southwest (known collectively as the Pueblo, after their distinctive style of architecture) revolted. The Pueblo had been in conflict with the Spanish colonial population for nearly a century, partly due to the encomienda, a system that allowed Spanish colonists to exact tribute from the native population in the form of labor or material goods in exchange for the supposed benefit of religious instruction. Not surprisingly, the Pueblo people resented being forced to ‘pay’ for the privilege of being being converted to Catholicism, especially when Spanish missionaries used the coercive power of the colonial administration to suppress the native religion by imposing harsh penalties on those found practicing or preaching according to the old traditions and the destruction of native religious paraphernalia.

In 1675, Spanish authorities arrested forty-seven Pueblo priests on charges of sorcery and subjected them to a variety of punishments including imprisonment, forced labor, public flogging, and even execution.

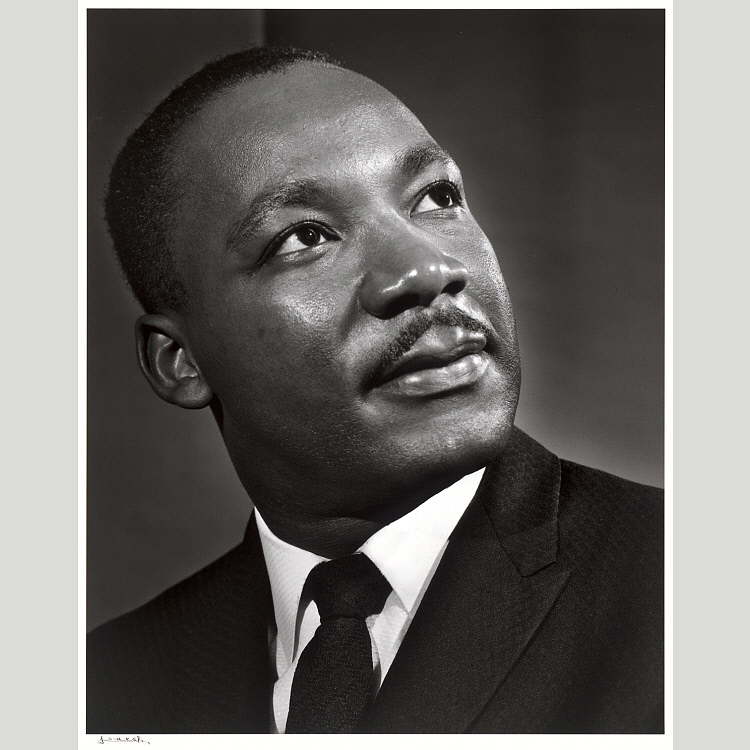

1898-1931. The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed September 19, 2016. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-3536-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

After his release from prison, one of these native religious leaders, Po’Pay, retreated to the Taos Pueblo where he received a vision that convinced him it was possible to coordinate the widely disparate Pueblo settlements for a combined attack against the Spanish. Oral tradition tells us that Po’Pay sent runners with knotted chords to each of the Pueblos in New Mexico with instructions that the community leaders were to untie one knot every day. When the knots were all undone, they would know that the day of the attack had come.

Following the revolt, Po’Pay toured the various Pueblo communities calling for a revival of traditional lifeways and religious practices. Po’Pay urged the Pueblo people to destroy all material evidence of the Spanish presence, including buildings, church records, religious statues, vestments. At the same time, he also encouraged them to construct new buildings in the traditional styles, including large public ‘dual-plazas’ with each plaza associated with one of the moities or kinship groups of the community. The dualism of traditional Pueblo society was linked to their religious worldview, which emphasized opposites and balance in nature.

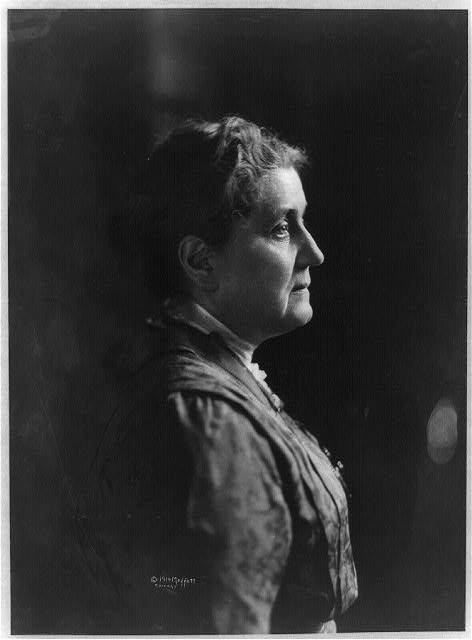

1854 | Seth Eastman. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed September 19, 2016. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-1bef-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

During the twelve years the Pueblos maintained their independence, they were able to reinstate many of the traditional religious practices that had been suppressed by the Spanish. Perhaps most significantly, they reopened the kivas (underground chambers) used for religious worship of their ancestors. Po’pay and his followers were so successful in their nativist revival that even after the Spanish returned to New Mexico in 1692, the Pueblo people retained a significant degree of self rule. Thus, the Pueblo communities were able to continue their religious practices virtually without interruption. Many of these festivals and ceremonies are still observed today.

Citation

Matthew Liebmann, Revolt: An Archaeological History of Pueblo Resistance and Revitalization in 17th Century New Mexico (University of Arizona Press, 2012).

Matthew Liebmann, “The Other American Revolution: Archaeology and the Pueblo Revolt of 1680,” lecture given at the Peabody Museum, Harvard University, 7 February 2013.