Salt Lake City, Utah

According to tradition, shortly after the Mormons were forced to flee Nauvoo, IL, Brigham Young experienced a vision of the territory where the religious community would be able to settle in peace.

“This is the place”: Experiments in Religious Freedom

Mormon pioneers about to enter Salt Lake Valley, July 24, 1847 . Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-113102.

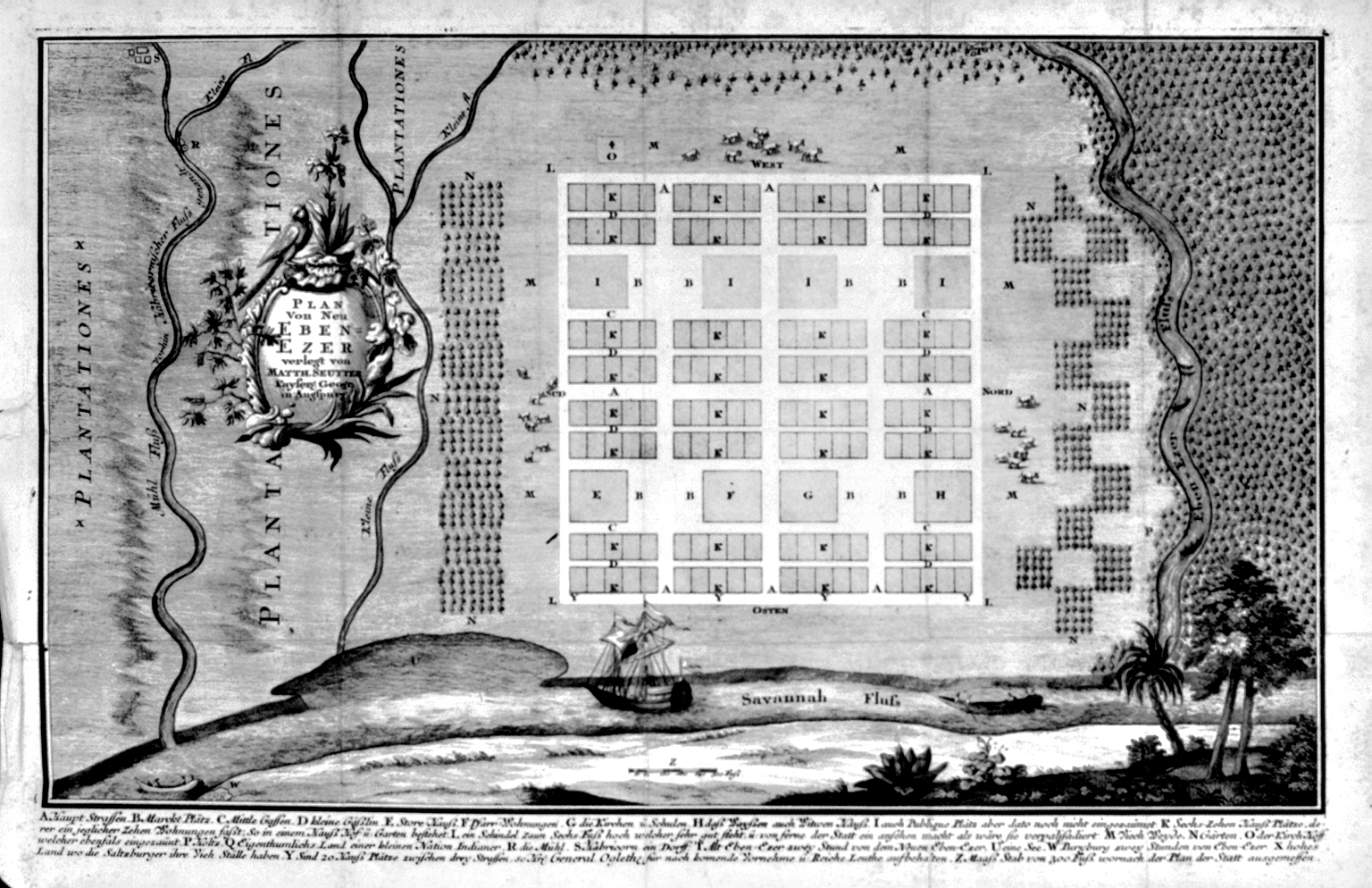

After traveling west for months, the pioneers reached the Salt Lake Valley on July 24, 1846, at which point Young is reported to have said, “This is the place.” Young and his followers took advantage of the uncertain status of the territory (it was part of the disputed land in the Mexican-American War) to organize their own government. Initially, the settlers relied upon their religious leadership to distribute homesteads and provide other basic civil services. In 1849, this informal government was replaced by a popularly adopted constitution forming the “provisional” state of Deseret. The name comes from the word for “honeybee” in the Book of Mormon, and was meant to signify the settlers’ commitment to the virtues of industry and community building. [You can read the constitution online: Laws and ordinances of the State of Deseret (Utah) (1851; reprint edition, 1919).]

Headed by Young (who was still serving as head of the LDS), the constitution of the state of Deseret was broadly modeled on the United States Constitution–unsurprising, given that the church’s Doctrine and Covenants teach that the Constitution was divinely inspired. Among the most notable features of the Deseret constitution was a very strongly worded statement on religious freedom:

All men have a natural and inalienable right to worship God according to the dictates of their own consciences; and the general assembly shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or to disturb any person in his religious worship or sentiments, and all persons demeaning themselves peacably, as good members of this State, shall be equally under the protection of the laws; and no subordination or preference of any one sect or denomination to another shall ever be established by law; nor shall any religious test be ever required for any office of trust under this constitution. [Article II, Section 3, Constitution of the State of Deseret; emphasis added]

The inclusion of protections for “religious worship” and religious “sentiments” was undoubtedly a response to the persecution Mormons had experienced in the more established parts of the country. Young and the other members of the LDS hierarchy were convinced that they had been unconstitutionally denied the free exercise of their religion not necessarily as a result of government action but rather, as a result of the government’s refusal to act to stop the often violent discrimination against the group by other citizens. Given the opportunity to devise their own statutes, Mormon leaders were careful to clarify their understanding that religious freedom required the positive protection of the state on the behalf of law-abiding religious individuals, and not merely that the state refrain from interference with religious activities.

Although the Constitution of the State of Deseret contained no formal language connecting the civil government to the Mormon faith, in practice, the territorial government was virtually indistinguishable from that of the LDS. Young served as the head of both church and state, and the members of the legislature were all high-level leaders of the religious organization as well. Even after the land became an organized territory of the United States (with its name changed to Utah) in 1850, there was relatively little change in actual governance: not only was Young the first territorial governor, but the first act of the Utah Territorial Legislature in October 1851 was to ratify the existing laws of the state of Deseret.

The Polygamy Question

Although polygamy was not required under Mormon teachings, in the absence of a federal law on the question, Young and the rest of the LDS leadership believed they were within their constitutional right of free religious exercise to endorse the practice of plural marriage within the Utah Territory. Public sentiment from the rest of the United States was decidedly negative: the Republican Party Platform of 1856 stated “it is both the right and the imperative duty of Congress to prohibit in the Territories those twin relics of barbarism — Polygamy, and Slavery.” Even after Congress passed the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act in 1862, LDS leaders continued to argue that plural marriage was a matter of religious freedom.

“A Mormon “Saint” and wives.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1878. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-b2e0-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Active conflict between the Mormon hierarchy and the federal government over the church’s continuing advocacy of polygamy was temporarily avoided by the Civil War but resumed in the 1870s. The issue was sensationalized when Ann Eliza Young, who described herself as Brigham Young’s nineteenth wife, filed for divorce on the grounds of neglect, cruelty, and desertion. After the divorce was finalized, Mrs. Young began a nation-wide speaking tour (including testifying before the United States Congress) in which she described “the degrading slavery in which the women of Utah [were] kept.”

During the same period that Mrs. Young was speaking against the church’s practice of plural marriage, her ex-husband was working with other LDS leaders to construct a test case challenging the constitutionality of the Morrill Act. George Reynolds, a minor administrator in the church, allowed himself to be charged as a bigamist. His defense argued that because Reynold’s multiple marriages were motivated by his religious faith, they should be regarded as constitutionally protected religious exercise. In the 1879 case Reynolds v. United States, the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the Morrill Act, stating: “Laws are made for the government of actions, and while they cannot interfere with mere religious belief and opinion, they may with practices.” Nevertheless, the church continued to openly teach plural marriage until 1887, when (under the Edmunds-Tucker Act), the U. S. Attorney General began legal proceedings to seize church property.

Faced with the legal dismantling of the church as an institution, LDS president Wilford Woodruff issued a statement ending plural marriage. Known as the Woodruff Manifesto, the statement framed the reversal of the church’s position as a matter of choosing the lesser of two evils:

The question is this: Which is the wisest course for the Latter-day Saints to pursue—to continue to attempt to practice plural marriage, with the laws of the nation against it and the opposition of sixty millions of people, and at the cost of the confiscation and loss of all the Temples, and the stopping of all the ordinances therein, both for the living and the dead, and the imprisonment of the First Presidency and Twelve and the heads of families in the Church, and the confiscation of personal property of the people (all of which of themselves would stop the practice); or, after doing and suffering what we have through our adherence to this principle to cease the practice and submit to the law, and through doing so leave the Prophets, Apostles and fathers at home, so that they can instruct the people and attend to the duties of the Church, and also leave the Temples in the hands of the Saints, so that they can attend to the ordinances of the Gospel, both for the living and the dead? [Official Declaration 1, Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]

As a result of this public repudiation of the doctrine (Joseph Smith’s “original plural marriage revelation is still included in the canon of Latter-day Saint scripture”[1]), in 1894 Congress invited the territorial legislature to apply for statehood. The Enabling Act specified the terms a prospective state constitution would have to meet in order to gain acceptance by the Senate. After specifying that the form of the government of the state had “not to be repugnant to the Constitution of the United States and the principles of the Declaration of Independence,” the Act declared:

First. That perfect toleration of religious sentiment shall be secured, and that no inhabitant of said State shall ever be molested in person or property on account of his or her mode of religious worship;Provided, That polygamous or plural marriages are forever prohibited. [Section Three of the Enabling Act of 1894]

The Utah Constitutional Convention agreed to abide by the specifications of the Enabling Act and on January 4, 1896, Utah became the 45th state. Yet despite the legal and religious statements rejecting future plural marriages, the issue continued to plague Utah’s political participation in the Union due to complications arising from existing plural marriages, and questions about the application of Woodruff’s Manifesto to Mormons living outside of the United States.

Although officially no new plural marriages were solemnized by the LDS within the United States after the Woodruff Manifesto, some church leaders continued to unofficially sanction the practice of plural cohabitation. Others believed that the tenor of Woodruff’s statement left open the possibility of performing plural marriages outside of the political jurisdiction of the United States and they encouraged Mormons who felt called to such marriages to emigrate to Mexico or Canada. Finally, even among those who believed Woodruff’s Manifesto had truly forbidden all future plural marriages, decency and compassion seemed to require the church continue to recognize those plural marriages already existing in 1890.

The Seating Controversies of B. H. Roberts and Reed Smoot

The religious and legal status of such ongoing plural marriages were the source of political controversy in the case of congressional candidate B. H. Roberts. Although he won election to the House of Representatives in 1898, Roberts was denied his seat in Congress on the grounds that his continued participation in multiple marriages made him a felon (under the Edmunds-Tucker Act).

The real objection to Smoot. by Udo J. Keppler. Puck Magazine: 1904 April 27. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-25844.

The issue died down for a time after the Roberts hearings, since no other members of the Utah Congressional Delegation were themselves polygamists. The election of Reed Smoot–a member of the highest governing body of the LDS Church–to the Senate in 1903 reinvigorated the controversy, however. Although Smoot was personally monogamous, it was alleged that his position as an Apostle in the LDS made him legally responsible for the church’s ongoing sanction of plural marriages in existence prior to the Woodruff Manifesto. The Smoot case became a sort of unofficial investigation into the LDS, as his position on the governing body of the church raised the question of his personal culpability for the church’s practices and doctrines that seemed antithetical to American laws and customs. In a victory for religious freedom, Smoot’s personal beliefs were deemed irrelevant to his fitness for office and he was eventually allowed to take his seat (and, indeed, he would serve in the Senate for thirty years).

During the course of the three-year hearings on the question of whether or not Smoot should be seated, it became clear that a limited number of new plural marriages had been solemnized by the LDS Church, albeit not in the territory of the United States.

In light of these revelations, on April 6, 1904, acting in his capacity as president of the LDS church, Joseph F. Smith issued a “Second Manifesto” on the question of polygamy. Smith’s statement clarified that the church’s rejection of plural marriage was binding upon all Mormons, regardless of their geographic location or the tolerance of such a practice by the civil authorities in their particular jurisdiction. Although a few polygamists whose marriages pre-dated the 1890 Woodruff Manifesto would remain in positions of church leadership through the first quarter of the twentieth century, the Second Manifesto marked the official end of the practice of plural marriage.

Sen. Reed Smoot, right & Heber J. Grant, Pres. of Mormon Church, left. [between 1918 and 1920]. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-npcc-00716. Grant was the last president of the LDS Church to have practiced plural marriage, although only one of his wives was still living by the time he became president of the church in 1918.

And I hereby announce that all such marriages are prohibited, and if any officer or member of the Church shall assume to solemnize or enter into any such marriage, he will be deemed in transgression against the Church, and will be liable to be dealt with according to the rules and regulations thereof and excommunicated therefrom. [“Official Statement by President Joseph F. Smith,” Deseret Evening News, Apr. 6, 1904, 1.]

Notes

[1] Richard Lyman Bushman, Mormonism: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 89.