Settlements and the Church’s Duty

Ellen Gates Starr

August 15, 1896

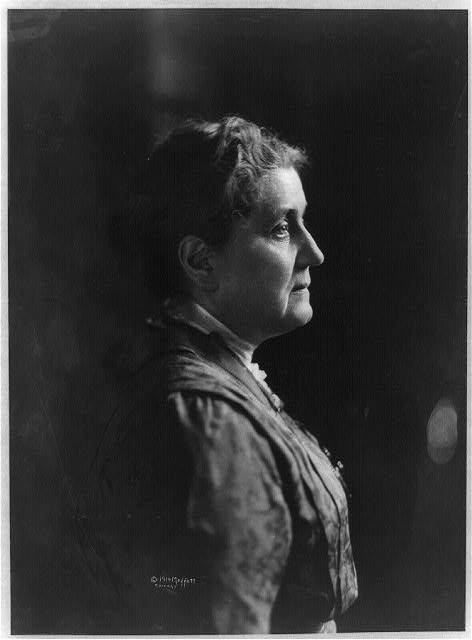

Ellen Gates Starr (1859-1940), co-founder of Hull House, was much more overtly religious than her better-known colleague Jane Addams. In this piece Starr is surprisingly already looking with jaded eyes at its success, concerned that what was meant to be a palliative measure along the road to social integration and equality for the laboring classes has become instead an end in itself.

Introduction

Although she was at this time in her life a member of the American Episcopal Church, Starr clearly meant her message for the Christian community in its broadest sense since it was originally published in pamphlet form by the non-denominational Boston-based Church Social Union. The aims of this reform organization offer some insight into Starr’s message:

The purpose of The Church Social Union is (1) To claim for the Christian law the ultimate authority to rule social practice; (2) to study in common how to apply the moral truths and principles of Christianity to the social and economic difficulties of the present time; (3) to present Christ in practical life as the living Master and King, the enemy of wrong and selfishness, the power of righteousness and love. This purpose it would fulfill (1) by the publication, every month, of practical papers upon present social wrongs and remedies; (2) by the preaching of sermons enforcing the application of the life of Christ to the industrial and social life of man; (3) by the formation of reading clubs for the patient study of economic principles and of local conditions; and (4) by the increase in its members of the spirit of brotherliness and of the sense of personal responsibility.

“The Church Social Union,” The Churchman, May 22, 1897, 16.

Although her essay is practical in parts, its overall tone suggests that Starr was primarily attempting to fulfill the final goal of the organization, to “increase in its members of the spirit of brotherliness and of the sense of personal responsibility.” Without ignoring the genuine differences between persons of varying ethnic, education, and class backgrounds, she urges her readers to remember the more essential unity and equality of mankind–particularly stressing the bonds between believers in Christ regardless of education, wealth, or other markers of status.

These themes also reverberate in the essay in the sections on beauty and authenticity. Starr’s identity as an artist and member of the international Crafts Movement intersected with her religious understanding of beauty not as something subjective, but as a reflection of the highest reality, the mind and presence of God. Starr disdained the superficial and inauthentic. In the end, she calls upon the Church to engage in the work of social reform as an act of friendship modeled upon the example of Christ who left the perfection of heaven to become not only the saviour but the Friend of humanity.

Settlements and the Church’s Duty

… Some of the first residents in settlements are beginning to feel a great distaste for speaking and writing about them. The increasing demand for descriptions and explanations of “Settlement methods” promotes a fear that they are becoming “popular” as permanent institutions. Nothing, to the mind of some of us, could be more undesirable than that settlements should tend to perpetuate themselves. Their best and ultimately only useful function is to further a state of society which shall have no need of them. Should the tendency increase to regard a “Settlement,” with what it now implies of chasms to be bridged in our social life, as something in itself ideal and worthy to be perpetuated—another “institution” to be regarded more than the living soul—there will soon need be an organized “movement” to scourge, chasten and regenerate, if not to exterminate, “Settlements.”

What is coming to be known as “the settlement movement” had its origin, in America certainly, in a very real impulse to eliminate, by disregarding them, the unreal and artificial barriers of class and station (differences which exist only because people have chosen separateness instead of union) and to seek to work together for mutual good, as one community, on the basis that the real good for the individual and of society must be at one. The impulse was toward recognizing and acting upon the eternal and fundamental identities and likeness in men, and toward doing away with separations by minimizing them as far as is possible without affectation. The capacity to do this depends largely on power of vision. What we see determines us. Our Lord saw in several fishermen and a tax-collector His disciples, men to whom he could entrust His truth. Cimabue saw in a little lad keeping sheep the artist of Italy, just as Samuel saw in the same sight the true king of Israel.[1] There were all sorts of other things there to be seen, differences and barriers to minds which could not see the main thing. Some minds cannot see a friend and equal or superior in a man or woman whose speech or manners or apparel differs widely from their own. Samuel and Cimabue could….

One of the beliefs at the root of the impulse which expressed itself in the Settlement movement was the belief that the Holy Ghost is not conditioned by stations in life. We are taught this by the Annunciation and Incarnation, but we have often forgotten it.[2] Indeed, in practice, it is seldom remembered, even in the Christian Church.

It is difficult to proceed upon a simple basis of actuality, so long have artificial distinctions been the foundation of our working hypothesis. People on either side [of] the artificially erected barrier are trammeled by it unless they chance to be of large insight or of a genuineness and directness of character which verities impress rather than semblances, essentials more than accidentals. These can, indeed, establish themselves on an actual basis of relationship without pretense.

But also with good grains tares may grow up. On the one hand sentimentality—the affectation of an equality which does not exist—is in danger of gaining ground in settlements. On the other hand there is the tendency toward a mechanical institutionalism, a danger which increases as settlements grow larger, more numerous, more an accepted fact, and as the “Settlement idea” becomes a cult instead of a simple living of life and doing of duty where it is most needed and can be most effectual.

There can be no real friendship where there is any pretense at all. Things which are different must be acknowledged as different with recognition of their due and relative measure of importance, and of their causes and the means of changing them. It is useless to pretend, because we have at length grasped the idea that community of understanding with “working people” is a thing to be desired, that it is in all or most cases wholly possible. It is as useless to affect that education, custom or training can make no difference in the possibility of real intercourse and communion as to insist that there is a difference ordained from the foundations of the world which no effort or education can remove. The thing to be determined is what in education is a universal value, and how, with their help, to secure that for all who are now deprived of it. For we must work for it together. To work with people and not for them is an essential note of the settlement motif.

The second danger, the Charybdis to the Scylla of sentimentality, arises from our business-like way of setting about the making to order of something which has grown. This has largely been the method in this country with regard to the arts and to repositories of scholarship and learning; and it seems about to become a process of reduplicating settlements. We look upon some real and living thing—a growth—and bestow our approval upon it and exclaim: “Let us have one. How much does it cost? How many people does it reach? What are your methods? What results do you see?” These are the precise questions which are daily asked. One often fancies himself approached by an enquiring mind with the demand, “What methods do you apply in the Christian life, and what results do you see in the people you meet?” Alas, it is not wholly a question of methods. The letter killeth. The life-giving spirit reckoneth not results upon requirements.

For generations we have left the “unprivileged classes” to degenerate mentally and morally as well as physically by giving them too little use of their lungs, their muscles, their minds, too little wholesome and normal exercise for their emotions. Without concern of the fortunate and well-to-do they have breathed bad air, seen and heard ugliness wherever they looked, been deprived of all but the meanest reading besides being left no time or life for it. Suddenly they are offered “model tenements,” the privileges of library, concert, and picture gallery.[3] And bitter are the complaints if “those people” do not “appreciate” their advantages. It is strange that in an age which prides itself more than all else upon its science, that demands so unscientific should be so common. The tendency of every action to repeat itself, the accumulation of inheritance, are set aside: the slavery, cowardice, apathy, dullness, hopelessness, narrowness of life, and fear of starvation which have pursued father and children to the third and fourth generations and far beyond—all are forgotten; and we demand that the last and present generation shall arise at once to full, manly stature, stand upon its feet and open its eyes to the beauty (such as it is) of some one small spot furnished it of our bounty. How unreasonable an expectation, how unscientific, is this. Life cannot be thus redeemed in spots, in any fullness of redemption. We cannot hope, in the midst of ugliness, for any transcendent beauty. Beauty is born of beauty and grows by beauty. We shall have love of beauty and passion for purity among people who open their eyes upon it and are nurtured in its midst. Art is not to be taught to a people whose days are passed in sordidly making, for a livelihood, the ugliest and most useless things, merely by giving them the opportunity of drawing, by gaslight, once or twice a week. We shall have art again when life is artistic. Art must come back to life through the channel of its daily occupations. All life must be redeemed. If society is an organism, no part of it can be thoroughly saved without the whole. Let us not fancy that our little spasmodic efforts at reconstructing life in some particular corner are going to avail much unless they are founded upon principles which, if applied, would reconstruct life for us all.

Those principles are indeed included in Christian ethics, but they have not been applied to any extent in the practical teaching of the Church as regards the problems of modern life. For the serious teaching, with religious zeal, of the fundamental Christian doctrine of brotherhood we must look nowadays to the Labor Movement; and if we would make our efforts toward social regeneration most effective we must join them to that movement, imperfect as it is, and beset with dissensions within and without.

In all efforts to help wage-earners it ought to be kept in mind that the sense of justice, not the “philanthropic” temper, is becoming and requisite. What people like to call “charity” is far more popular than the cardinal virtue of justice. The all-including Christian Love, it is to be feared, does not often underlie our “charitable” acts. We ought, however, to understand that one cannot do “A charity” where he is in debt, until he has first canceled the debt; and the debt of society to wage-earners is so large that there is no possibility of charity in any assistance towards life or its ends which society can yet grant to them, as a class. It is painful to observe how few feel the responsibility of this just debt.

Supposing the residents of a settlement to feel the debt and to be animated by the healthy passion for justice instead of the morbid one for “doing good” in its cant and common sense, there are several ways in which they may serve the Labor Movement in its early, trade union stage. Wage earners need to meet together, to associate outside of their workplaces that they may cultivate an espirit de corps and overcome, as far as may be, the disintegrating force of differences of language, religion, and tradition: that a fraternal spirit, confidence in each other, an understanding of their own needs, may be developed among them, and may overcome, in part, short-sightedness and lack of fortitude, selfish self-interest and fear of want which often drives men to betray their cause. It is a great help simply to offer a place of meeting which will not draw on the slender funds in the treasury of a new and feeble union, even although no sage advice be added, nor anything except kindly human interest. If any of the residents chance to speak several languages they can be sometimes serviceable, supposing them to have the tact and understanding of the situation, as interpreters and in making the social connection between the various groups. They may also be able to help direct the attention of wage-earners to local improvements in their conditions which could be made by persistent and systematic demand; and they may perhaps even help them to see possibilities in legislation for the benefit of their class—the greatest help they could give.

If what has been finely called the “instinct for mutualness” could be extended widely enough it would redeem the world. It is the distinctive note of the capacity to be civilized, social, religious. I have nowhere seen more genuine manifestations of it than in trade unions. During the garment-workers’ strike of ’96 in Chicago, hundreds of Jewish tailors sat huddled together day after day, hungry, uncomfortable, with a dreary prospect of days and weeks of suffering, to win or fail together, no one willing to be saved alone. There was among them an understanding, in many cases intellectual, in others imbibed and instinctive, of their need of each other. They failed. Even the magnificent street-railway strike in Milwaukee which followed soon after, could not wholly win, though the sense of justice and mutual helpfulness impelled citizens to go afoot willingly for weeks, a sight for which we ought to have thanked God.

At its best the trades union is inadequate. It is too narrow of scope. Supposing a perfect trades union (which would be an exercise of the pure imagination) it would not meet even its own necessities in time of great stress. A perfect union would mean one including in its membership all the workers in the trade, one in which there was complete harmony and absolute loyalty to the principle of mutual support and mutual endurance. Such a compact body would have much power in working for the improvement of its conditions of life, but it would be helpless against a more inclusive organization, against all organized labor. So far, wage-earners have little else than their unions to depend upon. Ultimately they must rely on legislation, which they will have chiefly to secure for themselves. In order to secure it there must be a social movement wider than the trades union movement. It is still too much the rule that each union is satisfied of doing well, if it cares for itself. The instinct for mutualness must transcend the line of trade; workers must see that this is their own salvation, as well as feel that their brothers’ salvation is their concern.

To some of us in the settlements which are in near relation to trades unions this truth becomes clear, and it therefore becomes part of our duty to proclaim it. But how many of us, wherever we live, feel deeply that there can be no conflict between the real good of society and of the individual? What we have chosen to regard as society’s good, the gospel of competition and all its fruits, is, indeed, often in conflict with the individual, mortal to him. If he remains true he is not infrequently sacrificed utterly. Even if he does not stay quite at the level of the hero, the opportunities of the unionist for unpicturesque martyrdom are ample.

If settlements can help people to see a little more clearly and justly the truth about these things, it will avail more than many years of sending little knots of children for country outings, or teaching them to hoard pennies, or mold clay—admirable as these objects are; because when all workingmen shall be able to feed, clothe, and educate their children, and shall not need infant assistance to eke out the family support, all this of the pennies and the day in the country will not need to trouble us. Wage-earners will be able to look to these matters themselves, and will assuredly much prefer to do so.

The church’s activity in furthering the Labor Movement has been, in this country, very slight. With few exceptions, very slight, also, has been her manifested sympathy with settlements in their broader aims, though some of them are the home of loyal children of the Church….

Simple-minded, sincere people go placidly on with toilsome effort, sewing garments and distributing food for a mere handful whom undercut wages and other “business methods” have made destitute, thankful for a good, large donation to their charities from some rich parishioner who has practiced the methods successfully and can afford the luxury of benevolence out of his profits. This is blindness on the one part, juggling with Christian charity on the other. If the church at this time excludes from its functions setting hand to the mending of such a state of things, we, as Christians, must reinforce secular justice, mercy, and truth.

The work of clothing the naked and feeding the hungry in body, mind, and soul cannot be altogether suspended while the emancipation of labor from bondage goes on. Churches must engage in it to some extent and under some circumstances, and settlements must. The mere bodily ministration, however, should be but a passing expression of sympathy and brotherhood which can never be satisfied except in doing away with the necessity for expression of such kind. While there is need of it, our sympathy might well be doubted were it withheld.

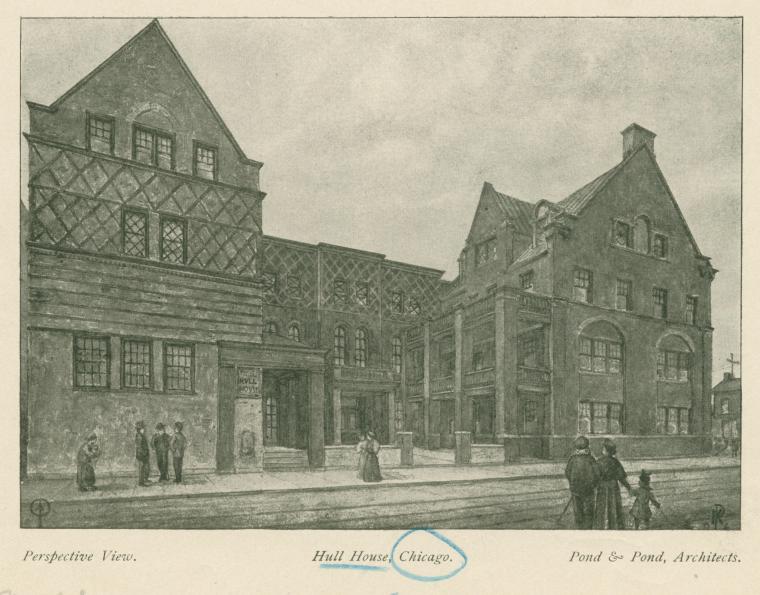

Aside from the function of fusing by the warmth of real social intercourse and friendliness the divergent and estranged parts of a city, which is the chief characteristic [of] settlement function, most of the American settlements, whether wisely or not, have done a good proportion of nursing the sick and relieving the destitute. But it has not been thought wise in most of them to allow personal ministration to the sick and needy, individual care of children, or even practical experiments in education to absorb all our resources of time, energy, and space. Whenever a widely effective measure toward industrial reform is in question some residents have held that such measure ought to be of first importance, since all educational and philanthropic ends, and we believe, all moral ends, will be subserved by it. For example, much effort and time on the part of several residents of Hull-House was devoted to the passage of factory law in Illinois. The removal to schools of thousands of children from factories where premature breadwinning under every unwholesome condition is dwarfing them in body and mind, and the replacing of their labor by that of men, now idle, with consequent necessary increase of wage, would assuredly be a better and wider service than merely training a few individual children in the hours they can spare from their toil. But it takes a certain mental perspective to include such work in our Lord’s command, “feed my lambs.”[4]

The doing of such work requires, also, especial fitness for it and much knowledge of the conditions; and I would not have it supposed that the settlement has no place in its life for the energies of those whose bent is in the other directions. The social side of our life underlies everything we do. Even our connection with the labor movement began and continues largely in social relations, some of which have been very close and dear. Through social relations—human intercourse—all the life of a settlement house is more or less closely united, at least in spirit. As the functions of a settlement house become more differentiated it is not always possible for any one resident to follow all the details of another’s work, and we may perhaps go our various ways, which may be roughly grouped under the heads of educational, philanthropic, civil and purely social pursuits.

Each of us has his own personal friends, and here, as elsewhere, the best of our life is in our friendships, and of them the least can be said. Here the deepest side of life can be touched, and it is here that the influence of a religious atmosphere would be most felt. The weak side of the settlement is unquestionably in the absence of that religious atmosphere. Were the strong and genuine social life of the settlement wholly pervaded by the spirit of faith, these friendships might bear rich fruit of spiritual life. Because it is not so pervaded, shall we, as Christians, leave the field to the apostles of pure ethics?

Such movements as characterize the settlements of wider aim are going forward, if not with the church’s help and blessing, without it, to her and their inevitable loss. Those of us who are jealous of the churches’ honor would fain save her from the accusation that she alone of the powers of righteousness holds her hand—that she alone is not represented in this country, in the movement toward a wider social justice. Of the Church of England that cannot be said. There the part of the Church which is alive is in the front line of social reform.

The Christian vocation demands everything that we can possibly be called upon by our personal or social conscience to do. It is the church’s right to claim no less, though she does not do so. Should we not claim it all for our Lord and Master, remembering, as a motive to humility “in the foolishness of preaching” the example of Chaucer’s pilgrim parson: “Christe’s lore and his apostles twelve, he taught, but first he followed it himselve.”

Notes

[1] Cimabue (c. 1240-1302) was a Florentine painter and designer of mosaics who is generally regarded as the last of the Italo-Byzantine. According to tradition, while traveling through the Florentine countryside, Cimabue came across a young shepard boy amusing himself by drawing pictures of his sheep on the rocks in the field. Cimabue was so impressed by the boy’s skill, he purportedly invited him to become his apprentice at once, thus launching the career of the early renaissance artist Gioto.

Samuel was the last of the Hebrew judges and the first of the Old Testament prophets. According to the Bible, although Samuel at first hoped that his own sons would rise to positions of leadership over the people of Israel, they proved to be unworthy of such an honor. Instead, God used Samuel to identify the kings he had chosen for the people, first Saul, and then, when Saul proved unfaithful, the shepherd-boy David. See 1 Samuel 16:11-13. Return

[2] Here Starr refers to the revelation of the virgin birth to Mary by the angel Gabriel; see Luke 1:26-38 (the annunciation) and the Christian doctrine that Jesus as the second person of the trinity was co-existent with the Father from the beginning and that in the form of a human baby “the Word become flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth.” (the incarnation; see John 1:14). In Christian doctrine, both are examples of the idea that “God is no respecter of persons” (Acts 10:34) and that He often chooses to work through the poor, powerless or otherwise lowly members of society. Return

[3] Designs for so-called “model tenements” were popular projects of urban reformers: Catherine Beecher and her sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe presented one in their book Principles of Domestic Science (1870), and Felix Adler, head of the Ethical Culture Society, began building some in 1885. The other examples of programs Starr mentions were offered at Hull House. Return

[4] The allusion is to the biblical account of Jesus’ reinstatement of Peter after the resurrection; while breakfasting with the disciples, He asks Peter three times (to parallel Peter’s three denials of Christ during his trial) “Do you love me?” Three times Peter replies “yes, Lord,” and three times Jesus commands him “then feed my sheep.” (See John 21:15-20.) Christian commentators have generally understood the thrice-repeated command symbolically, as a reference to Peter’s calling as an apostle to teach and preach the gospel. Ironically, Starr’s interpretation, although unusual, is more literal. Return

Citation

Publications of the Church Social Union No. 28 (15 August 1896): 3-16.