Pale Horse, Pale Rider

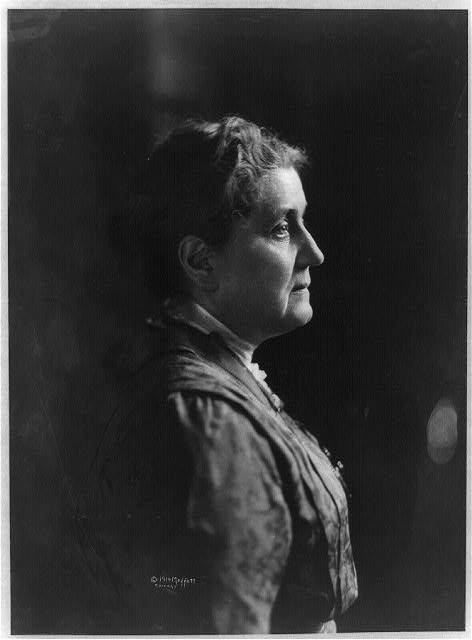

Katharine Anne Porter (1890-1980)

1939

Among fiction about Americans’ experience in World War I, Katherine Anne Porter’s novella “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” stands out for its finely drawn characters—young people bearing the burden of a conflict begun by their elders—and its lyrical depiction of the war’s cost.

A love story set on the American home front, “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” casts elegiac light on the religious and patriotic aspirations many young Americans brought to the war. Given that Porter published the story in 1939, when another war loomed, perhaps it also sounds a warning.

Katharine Anne Porter, between 1944 and 1953. Painting by Marcella Comès Winslow. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; partial gift of John Winslow and Mary Winslow Poole

The main character, Miranda [1], works as a reporter for a city newspaper. When she and a soldier on leave fall in love, she senses the war will deny them a future together. Instead of answering this foreboding with scenes of battle, the story brings the battle home, in the guise of the devastating influenza epidemic of 1918.

Porter herself, working as a reporter for the Rocky Mountain News, had contracted the Spanish flu in 1918 and spent months recovering. The novella seems to portray Porter’s younger self: a woman who projects self-sufficiency yet feels vulnerable in a world that glorifies shallow patriotism, worships profit, and promises security only in private human relationships. Adam, the soldier Miranda loves, embodies the manly virtues that pro-war voices had declared the conflict would call for from young men, including a determined American optimism. Adam views with generosity the efforts others–even those declared ineligible for the draft–make to rise to the challenge of war. Miranda, however, musters only pluck and determination as she silently objects to those who sentimentalize the war (young ladies in a social club who bring candies and cigarettes to horribly wounded soldiers) and those who try to profit from it (Liberty Bond salesmen).

Taking the title of the story from a hard-to-trace traditional Negro spiritual that itself uses a symbol of death drawn from the book of Revelation, Porter implicitly compares her generation’s experience with that of a people whose aspirations American society repeatedly frustrated. One might compare Miranda’s wary reserve in the midst of war propaganda to the wariness of African Americans in a hostile Jim Crow world. Instead of shared faith and purpose, war has put “fear and suspicion” into her fellow citizens’ eyes,

. . . as if they had pulled down the shutters over their minds and hearts and were peering out at you, ready to leap if you make one gesture or say one word they do not understand instantly.

The story’s climax offers a beautiful vision of the afterlife in which the necessary exhortations of civic life are forgotten and one’s private connections with family and friends are transcendent.

Notes

[1] Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. [Return]

Citation

Albert Pinkham Ryder, The Race Track (Death on a Pale Horse), oil on canvas, c. 1896-1908. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.