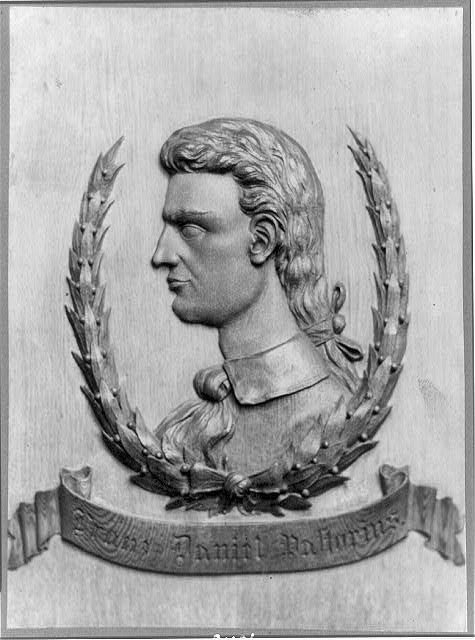

Lonely Dissenter: Jane Addams’ “Personal Reactions in Time of War”

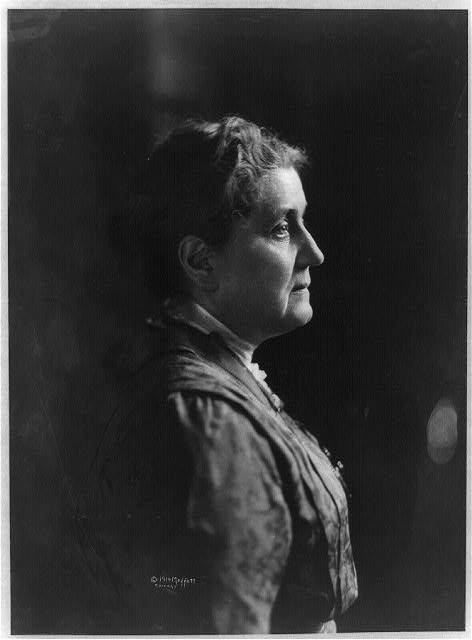

Jane Addams

1922

In her essay “Personal Reactions In Time of War,” Jane Addams describes her experience as an opponent of World War I while pro-war activists were framing the war as a holy crusade to protect democracy.

In her essay “Personal Reactions In Time of War,” Jane Addams describes her experience as an opponent of World War I during a time of growing pro-war sentiment in the US, fed by government and media propagandists. By 1922, when Adams wrote the book from which the essay is drawn (Peace and Bread in Time of War), disillusionment had succeeded enthusiasm for America’s entry into the European conflict. The war had been promoted to those who enlisted as both a test of personal manliness and a holy crusade to protect democracy. Yet it did not fulfill these expectations. A new kind of warfare, characterized by constant shelling along a nearly immovable front line, did not offer clear opportunities for individual heroism. Most often, it pitted relatively helpless human beings against impersonal machines of destruction: mortars, artillery, flamethrowers, and poison gas. More important, instead of completely disabling German aggression against self-determining, democratic nations, the war ended in an armistice between the exhausted foes. Nevertheless, the changing American view of the war did not bring Addams back into harmony with public opinion.

Isolationism vs. Internationalism

Americans reacted to their experience in World War I by re-embracing their customary isolationism. Hence, when the League of Nations convened for the first time on January 10, 1920 (one hundred years ago this month) the United States was not among the founding members. Although President Woodrow Wilson had campaigned hard in favor of it, Republican Senators had persuaded their colleagues that membership in the league would deprive Americans of control over their own foreign policy; it would draw the US into each new European conflict.

Peace Delegates on NOORDAM, the oceanliner that carried American delegates across the Atlantic — Mrs. P. Lawrence, Jane Addams, Anna Molloy, Bain News Service, 1915. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-18848.

Addams herself, during the war, had dared to hope that international efforts to mediate the conflict might end it. She served as president of the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace, a group formed in 1915 and headquartered in Amsterdam, which called for neutral parties to engage in immediate and continuous mediation between the belligerents. Addressing the group—whose members included women from both warring sides—Addams said that “profound and spiritual” forces had brought them together. Women, she said, understood that “there are universal emotions which have nothing to do with natural frontiers.”

Adams then began traveling to various meetings, some with foreign and prime ministers of the warring nations, testing the possibility that an international mediation group might propose a workable peace plan. She joined other groups pushing for peace, including the predominantly Quaker group Fellowship of Reconciliation, while also helping Herbert Hoover and the Commission for Relief in Belgium in his efforts to gather food to send to European civilians suffering wartime shortages. After the armistice, she led the ICWPP in a Second Congress in May 1919 in Zurich, while the Paris Peace Conference convened. They endorsed the proposal for a League of Nations.

Addams Reacts to Misrepresentations of Her Pacifism

Addams at her writing desk, ca 1912. Library of Congress, LC-USZ61-144.

Throughout her antiwar activism, Addams was criticized in the pro-war American press—with increasing viciousness as a decision to enter the war neared. Moreover, her anti-war views put her at odds with prior allies who thought that “militarism might be used for advanced social ends.” If war brought the nationalization of the coal industry or railroads, it might also bring more enlightened labor practices in these sectors. Addams objected “that social advance depends as much upon the process through which it is secured as upon the result itself.” Functions managed by government during wartime could easily return to private hands afterwards. Permanent social reforms would occur, she thought, only through democratic processes—that is, when voters were persuaded to favor reforms.

Advocates for war accused Addams of lacking both respect for the soldiers’ courage and understanding of national defense needs. Progressive allies urged her to preserve her effectiveness by abandoning an unpopular view. Pressured from both sides, Addams experienced depression and self-doubt, followed by righteous indignation. Neither mood was natural to her.

Trading the Mediator’s Role for that of the Prophet

Press Correspondents with Lillian Wald and Jane Addams, Harris & Ewing, 1916. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-hec-07331.

Working among the immigrant community in Chicago, Addams had been keenly attentive not only to their needs, but also to their customs and ethical expectations. At the same time, she had inquired into the practical difficulties faced by city administrators and studied the political motives that made them resistant to reform. Her responsiveness to those she worked among kept her from arrogantly insisting on her own point of view. It allowed her to advance innovative, win-win solutions to social problems.

World War I thrust Addams into a lonely spotlight, since her usual method of inquiry and negotiation met only implacable opposition. This essay explains how she slowly came to accept the failure of her efforts, while understanding that her highest calling was faithfulness to the truth as she understood it.