Flannery O’Connor’s Mystery and Manners: Manifesto of a Christian Writer in an Era of Unbelief

Flannery O'Connor

1969

Flannery O’Connor’s prose collection Mystery and Manners appeared fifty years ago, offering the posthumous manifesto of a Catholic writer in a mostly unbelieving society. In the Southern Bible Belt, O’Connor found the vestiges of a long faith tradition—and the material she needed to depict human lives as salvation histories.

Often described—and misread—as an elaborator of the “Southern Gothic,”[1] Flannery O’Connor saw herself writing within a long faith tradition that, in the century prior, had been eclipsed by a reliance on science to alleviate human suffering. The essays in the collection Mystery and Manners, many of them composites drawn from published work and talks to academic, literary, and Catholic audiences,[2] describe her uncomfortable relationship with readers who wanted a literature that would affirm their optimism about post-war American progress.

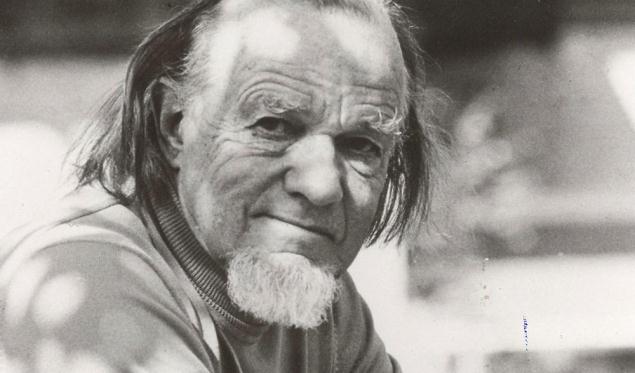

Flannery O’Connor, photographed by Joseph Reshower, 1961 (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; acquired through a partial gift by John Daniel Reaves).

But the essays also show her fundamental disagreement with other similarly admired, yet not popularly read, authors of her era. These writers also described a discontent that science could not relieve. But its source lay in a loss of faith that scientific advance had caused. O’Connor retained a Christian understanding of humanity’s fundamental predicament.

Catholic Writer in the Protestant South

A deeply committed Catholic, O’Connor spent most of her life among Protestants of the Southern “Bible Belt.” She grew up in Savannah, Georgia and spent the last third of her life on a farm in Milledgeville, Georgia, capital of the state during the antebellum and Civil War period. One might assume her religious minority status and liberal social outlook led to a detachment from, and eventual sardonic portraiture of, her neighbors. Even if true, O’Connor devoted serious, respectful attention to her fellow Southerners’ speech and actions. Their “manners” supplied the concrete, realistic particulars she used to make fiction. Their religious convictions pointed to the “mystery” that most concerned her.

Old Governor’s Mansion, Clark & Green Streets, Milledgeville, Baldwin County, GA, photographed by Branan Sanders, March 1934 (Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, HABS GA,5-MILG,1–2).

With the failed cause of the Confederacy looming over their present efforts, Southerners lacked the optimistic “innocence” that still colored much of American culture. “In the South we have, in however attenuated a form, a vision of Moses’ face as he pulverized our idols,” O’Connor writes in “The Regional Writer” (59). Like Moses’s obstinate Israelites, she implies, most white Southerners were still unable to comprehend God’s disapproval of their cause. Their latent insecurity made them more open to mystery.

Slave Cabin, Milledgeville, Baldwin County, Georgia, photographed by Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1944 (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-csas-00984).

Mystery and Manners makes clear that, however pointed—and hilarious—her satires of Southern characters, O’Connor saw them occupying the same urgent space she did, between birth into sin and potential salvation in Christ. What she meant to satirize was neither religious delusion in the rural poor nor even especially the foolish pride of the impoverished gentry. It was the way sin distorts all human self-understanding.

Locating Hope in Modern Life

In the selection “On Her Own Work,” O’Connor explains her purpose through an extended discussion of her famous story, “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” She tells of meeting a professor who taught the story at a Southern college. He said he could not convince his students that the grandmother in the story is a hypocrite who receives her comeuppance at the hands of a mass murderer, the desperate unbeliever who calls himself “The Misfit.” O’Connor informed the professor that his students knew better. “They all had grandmothers or great aunts just like her at home, and they knew, from personal experience, that the old lady lacked comprehension, but that she had a good heart” (p. 110).

Like many of her stories, “A Good Man is Hard to Find” culminates in catastrophe, seemingly denying us the comic conclusion we expect from Christian fiction. Yet we will read the story as tragic or absurd only if we fail to understand it as a salvation history. Just before the story ends, the grandmother reaches out to The Misfit in a sudden awareness that she is “joined to him by ties of kinship which have their roots deep in the mystery she has been merely prattling about so far.” Admitting that the grandmother’s gesture puzzles many readers, O’Connor notes that,

Our age not only does not have a very sharp eye for the almost imperceptible intrusions of grace, it no longer has much feeling for the nature of the violences which precede and follow them. . . . I suppose the reasons for the use of so much violence in modern fiction will differ with each writer who uses it, but in my own stories I have found that violence is strangely capable of returning my characters to reality and preparing them to accept their moment of grace (p. 112).

Cover of Mystery and Manners, By Flannery O’Connor; selected and edited by Sally and Robert Fitzgerald (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1969).

To the popular complaint “that the modern novelist has no hope and the picture he paints of the world is unbearable,” O’Connor replies sharply: “People without hope not only don’t write novels, but what is more to the point, they don’t read them. They don’t take long looks at anything, because they lack the courage” (p. 78).

Believing Writer in an Unbelieving Society

One might object that O’Connor’s profession of hope fails to account for the novels of writers like Albert Camus. O’Connor indirectly admits as much. She divides her contemporaries into three kinds of authors, with three different “spiritual” orientations. One type, typified by Steinbeck, “recognizes spirit in himself but fails to recognize a being outside himself whom he can adore as Creator and Lord; consequently” man himself “has become his own ultimate concern.” Another type “recognizes a divine being not himself” but, disbelieving that human beings can know this divinity, “wanders about, caught in a maze of guilt he can’t identify, trying to reach a God he can’t approach, a God powerless to approach him.” A third type “can neither believe nor contain himself in unbelief” and therefore “searches desperately . . . for the lost God” (159).

O’Connor puts Camus, Kafka and Hemingway in the last category. She credits them with pushing Christian authors “to examine our own religious notions, to sound them for genuineness, to purify them in the heat of our unbelieving neighbor’s anguish.” But ultimately the Christian writer returns to exploring “the central religious experience,” that is, “the experience of an encounter” that imparts life-changing knowledge (p. 160).

To pursue this calling, O’Connor had to overcome her audience’s biases. She faced the “sociological” bias that sees her characters as regional types; the “clinical bias . . . that sees everything strange as a case study in the abnormal” and what she calls an enthusiasm, too often amounting to condescension, for “compassion”:

I don’t wish to defame the word. There is a better sense in which it can be used but seldom is—the sense of being in travail with and for creation in its subjection to vanity. This . . . implies a recognition of sin; this is a suffering-with . . . which blunts no edges and makes no excuses. . . . Our age doesn’t go for it (164–166).

O’Connor saw herself writing in the wilderness, awaiting a time when “we have again that happy combination of believing artist and believing society.” Concluding her essay “Novelist and Believer,” she confesses that in her own time, she perhaps cannot hope to “reflect the image at the heart of things.” She might only reflect “our broken condition and, through it, the face of the devil we are possessed by.” Although she calls this “a modest achievement,” she understood that this work, too, was “necessary” (168).

[1] a mode of fiction ascribed to many Southern authors of the 19th and 20th centuries. It features abnormal or “grotesque” characters with strange preoccupations who transgress behavior norms.

[2] Mystery and Manners, selected and edited by Sally and Robert Fitzgerald (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1969). The Fitzgeralds were close friends who had shared their Connecticut home with O’Connor while she wrote her first novel, Wise Blood. After seeing to the publication of these essays, five years after O’Connor died of lupus at age 39, Sally would go on to collect and edit the author’s letters.