The Cane Ridge Revival

Cane Ridge, KY

August 1801

Cane Ridge was the scene of the first great Western Camp Meeting Revival

The Cane Ridge Revival established the camp meeting revival – an event of several days during which participants camped at the meeting site because of the distance they had traveled to get there – as a significant element of American Christianity. The personal history of the revival’s leader, Barton W. Stone, allows us to see other important elements of American religious and secular experience in the first half of the 19th century.

A remaining stand of cane (bamboo) behind the Cane Ridge meeting house

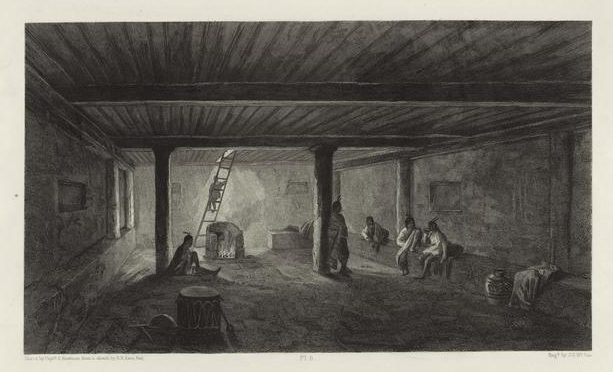

In 1790, a Presbyterian minister took his congregation west from North Carolina to what was then still part of Virginia, near what is today Paris, Kentucky, in the north central part of the state near Lexington. Daniel Boone had suggested to the minister that the congregation settle in the area, near the cane breaks on a ridge among rolling forested hills. The congregation built a simple log church or meetinghouse in 1791 on what became known as Cane Ridge.

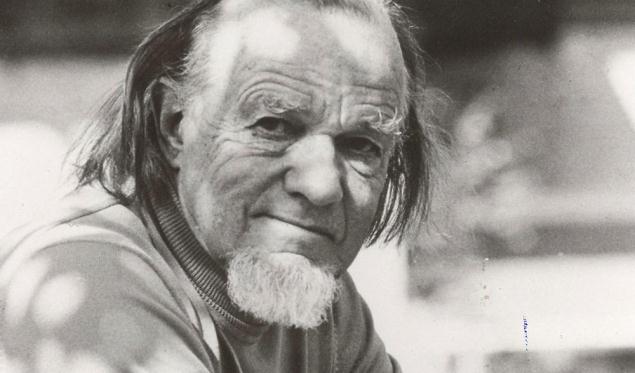

Barton W. Stone, 1772-1844

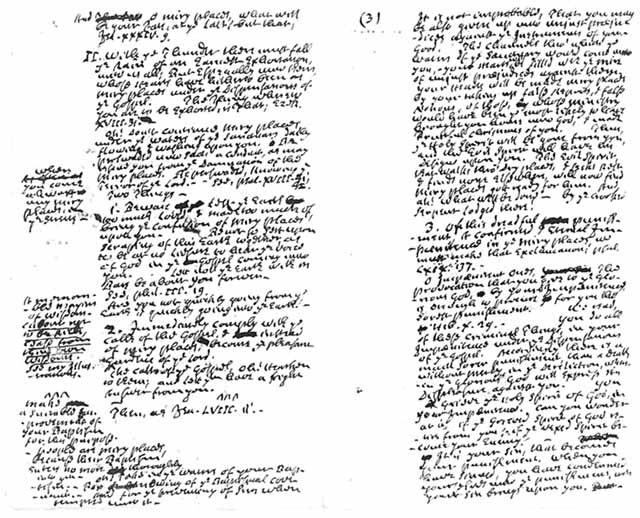

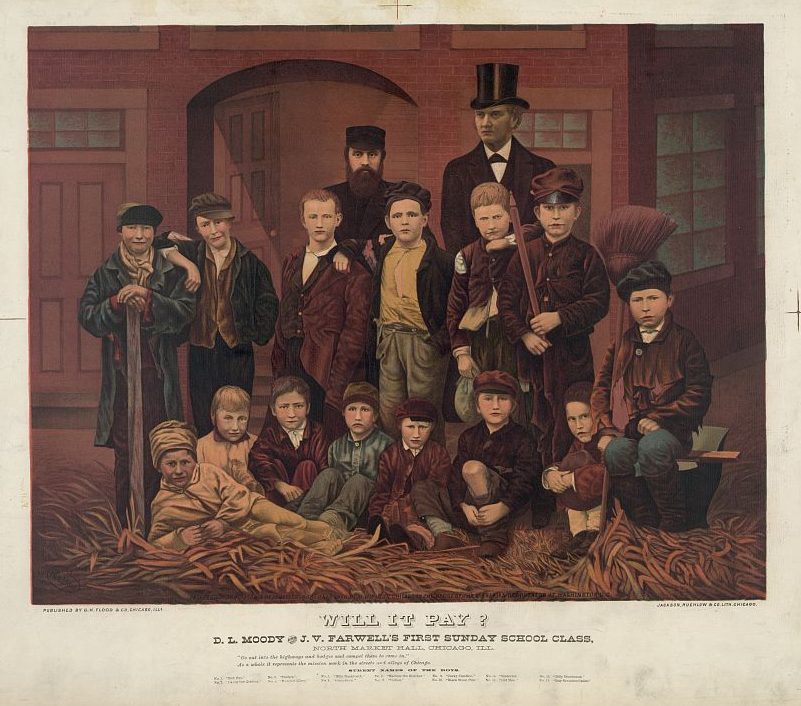

In 1798, Barton W. Stone (1772-1844) was ordained as the minister of the meeting house on the ridge. Stone, born in Maryland, moved with his family as a young boy to North Carolina. He had decided to become a minister while a student at a “log college” in Greensboro, North Carolina, after hearing James McGready (1758?-1817) preach. A Scots-Irish Presbyterian evangelist who had come to Carolina from Pennsylvania, McGready later moved to Kentucky, as did Stone, another Scots-Irishman. Stone attended a revival that McGready held in the summer of 1800 in Logan County, Kentucky, about 180 miles southwest of Cane Ridge. Impressed with what he experienced, Stone decided that he would conduct a revival of his own at his meetinghouse the next year.

Stone conducted a few preparatory revivals and then announced one for August 6. At the appointed time, a number of other Presbyterian ministers arrived, along with Baptist and Methodist preachers. So did large numbers of people, a crowd variously estimated at ten to twenty-five thousand, an extraordinary number, given that nearby Lexington, then Kentucky’s largest city, had a population of two thousand.

Pulpit of the Cane Ridge Meeting House

Historian Sidney Ahlstrom describes the scene:

“the milling crowds of hardened frontier farmers, tobacco chewing, tough spoken, notoriously profane, famous for their alcoholic thirst; their scarcely demure wives and large broods of children; the rough clearing, the rows of wagons and crude improvised tents with horses staked out behind; the gesticulating speaker on a rude platform, or perhaps simply a preacher holding forth from a fallen tree. At night, when the forest’s edge was limned by the flickering light of many campfires, the effect of apparent miracles would be heightened. For men and women accustomed to retiring and rising with the birds, these turbulent nights must have been especially awe-inspiring. And underlying every other conditioning circumstance was the immense loneliness of the frontier farmer’s normal life and the exhilaration of participating in so large a social occasion.”[1]

Under the influence of constant preaching and repeated communion services, the exhilaration of the event produced many conversions, as well as physical signs of ecstasy and transformation. Stone himself described people breaking out in hysterical fits of laughter, convulsed with jerking motions, running uncontrollably about the meeting site, or simply falling down on the spot “with a piercing scream . . . like a log on the floor, earth, or mud, and appear[ing] as dead. . . .”[2]

A view from the pulpit in the original log meeting house

Revivals occurred in other parts of Kentucky in the summer and early fall of 1801, and their example led to revivals in neighboring states over the next few years. Cane Ridge remained the biggest, and unmatched in the unusual physical effects it produced. The meeting, which came to an end only when food ran out, was a significant event, helping make revivals a core element of American Protestantism.

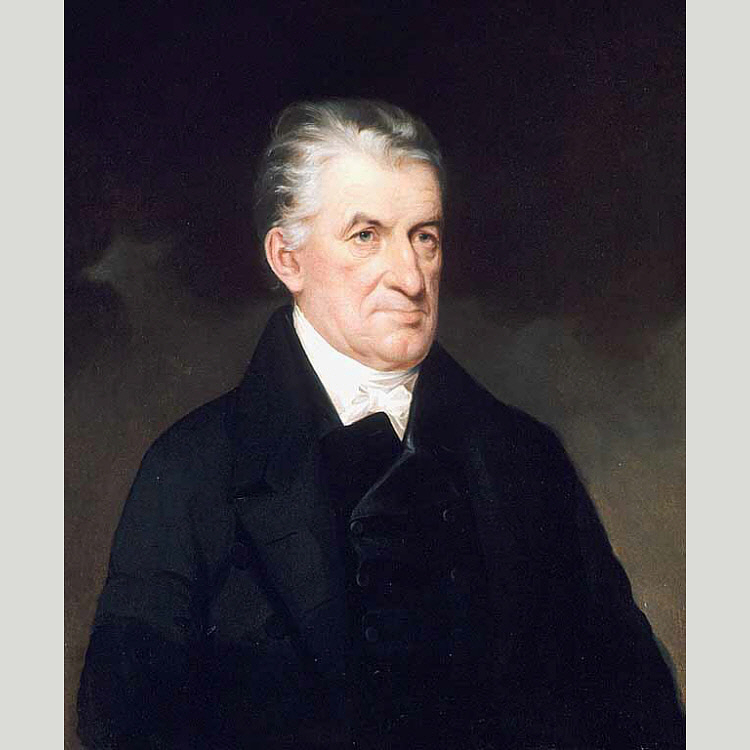

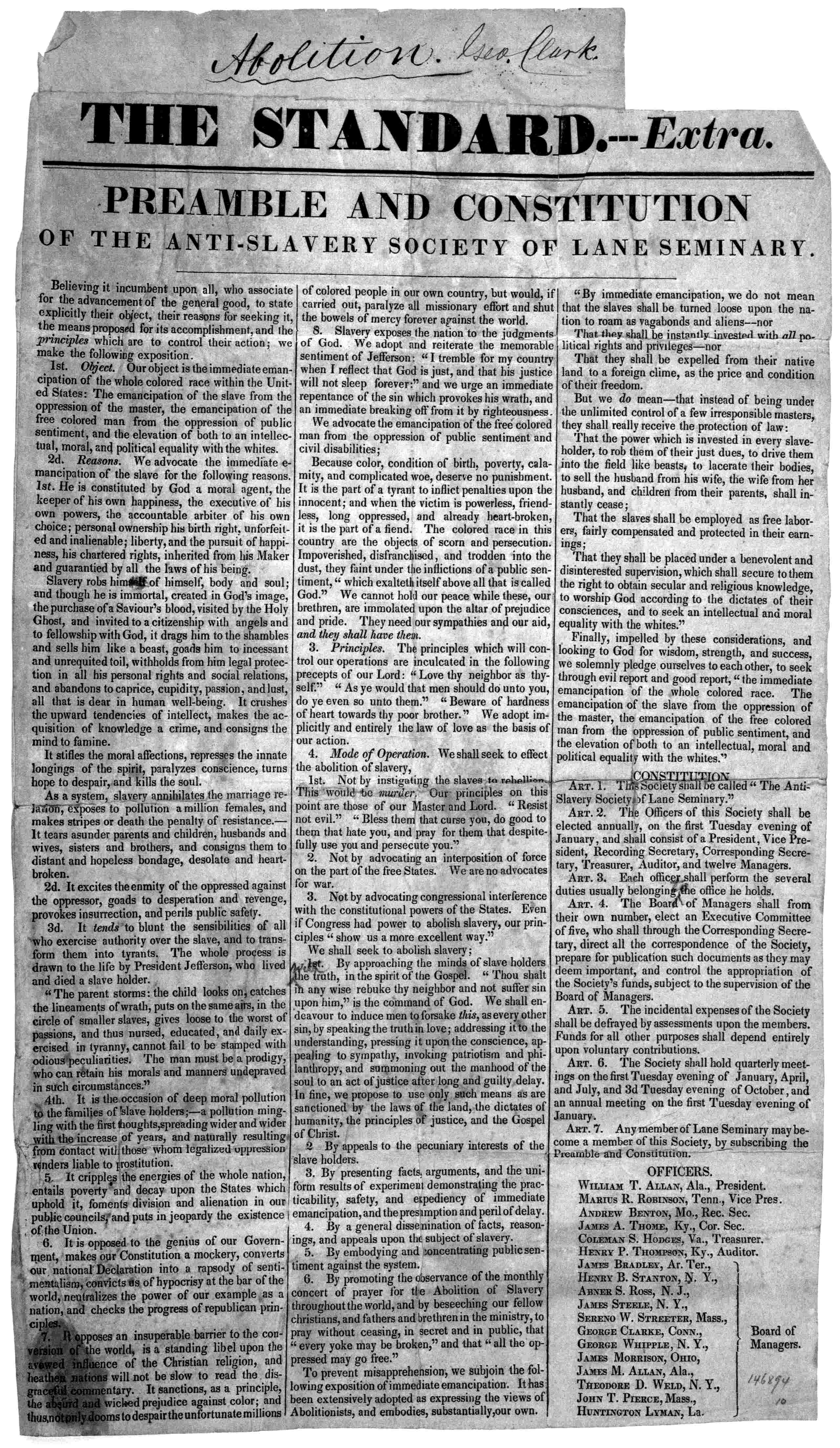

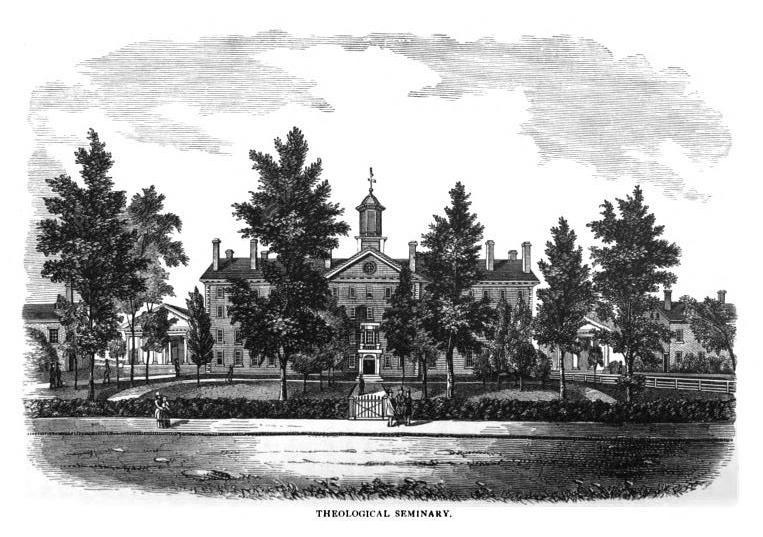

As news of the Kentucky revival and the details about Cane Ridge spread across the United States, it was not met with universal approval. As always in the aftermath of revivals, some questioned both their propriety and effectiveness. Did the conversions last? For his part, Stone came to believe that various aspects of Presbyterian doctrine, derived from the teachings of John Calvin, were in fact not biblically based. Stone questioned the notion of predestination, the requirement of an educated clergy, the idea that human will had no role in salvation, and the requirement for any Church governance beyond the congregation, for example by a Synod or council of churches, as in the Presbyterian Church. Eventually, Stone broke from the Presbyterians and started what he considered a strictly Biblical church movement whose members referred to themselves simply as “Christians.” Later merging with a similar movement started by the father and son team of Thomas (1763-1854) and Alexander (1788-1866) Campbell, also Scots-Irish Presbyterians, the followers of Stone became the denomination known as the Disciples of Christ.

In addition to its role in establishing revivalism and exemplifying the tendency in Protestantism – perhaps especially in American Protestantism – to return to the Bible, the story of Cane Ridge and Barton Stone exhibits the mobility of Americans in the early republic. In particular, the migratory pattern of Scots-Irish from Pennsylvania down the mountains valleys to North Carolina and then west to Kentucky was important in the settlement of the trans-Appalachian west. The Scots-Irish who settled in Kentucky, so vividly described by Ahlstrom, are the ancestors of the “hillbillies” elegized by J.D. Vance.[3] Some of them moved on, as Stone and Abraham Lincoln’s father (of English ancestry) did to Illinois. Others moved on to Ohio, Indiana or points south. Cane Ridge and Barton’s life reveal deep and still powerful currents in American life.

The stone church sheltering the original log meeting house at Cane Ridge

It is worth noting that the Cane Ridge revival occurred five months after Thomas Jefferson’s inauguration. We can only imagine what he might have thought if he had observed his fellow countrymen writhing in ecstatic communion with their God. Somehow, however, Jeffersonian rationalists and Christian revivalists both managed to survive and prosper in their new country.

[1] Sidney Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972), 433.

[2] Quoted in Ahlstrom, A Religious History, 434.

[3] J. D. Vance, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis (New York: Harper, 2016). Compare the remarks of Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 136–141.