A Plea for the West

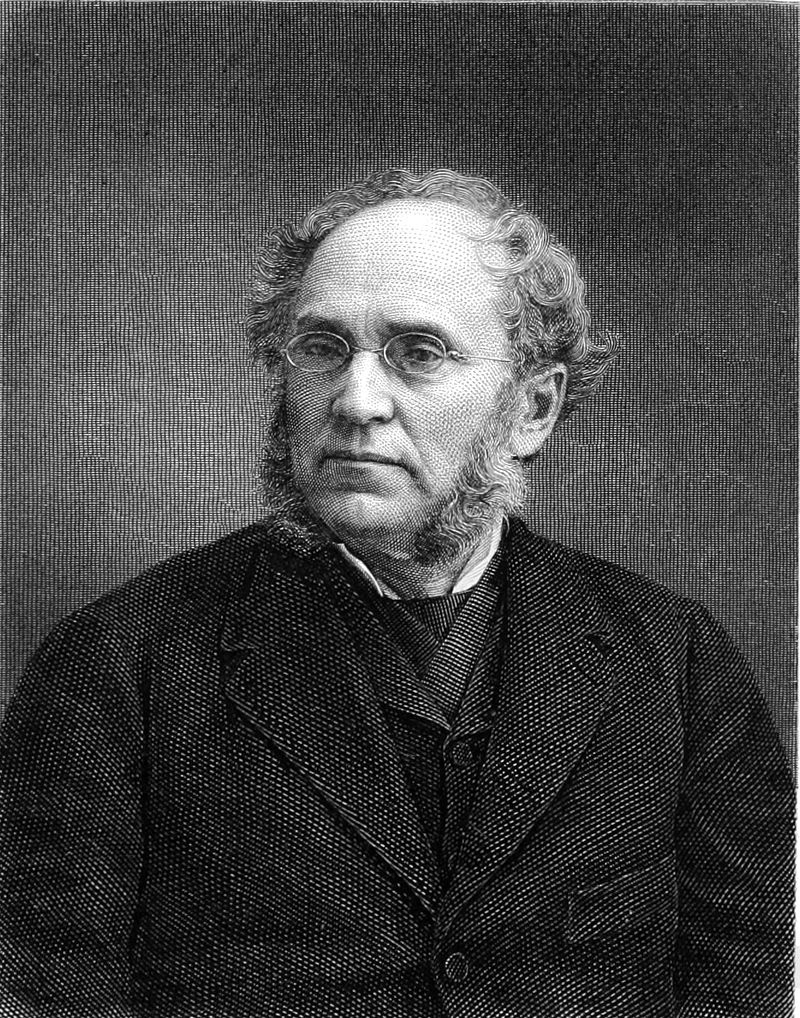

Lyman Beecher

1835

In this short tract, Beecher urged Americans to support protestant educational institutions in order to secure the “religious and political destiny” of the nation, which, he argued, hinged upon the Western spread of a protestant evangelicalism with deeply Calvinist roots.

One of the 25 Core Documents

Go to Study Questions

Introduction

Lyman Beecher (1775-1863), father of Edward Beecher and Henry Ward Beecher, moved from New England (where he had struggled to uphold the traditional Calvinism of the Congregational Church against the encroachments of Unitarianism) to Cincinnati, Ohio in 1832 to assume the presidency of Lane Theological Seminary. Shortly thereafter he published this pamphlet to stir up support for educational institutions (like Lane) that would help spread a protestant evangelicalism to the West. Although many of his contemporaries derided the tenets of the reformed tradition, American liberty, Beecher argued, was deeply rooted in the Calvinist theology of New England with its tradition of principled resistance to arbitrary power. The spread of religion, education, and liberty were interconnected, Beecher asserted—and all were equally threatened by the growing influence of Catholicism in the United States, with its historic associations with monarchical and even despotic regimes.

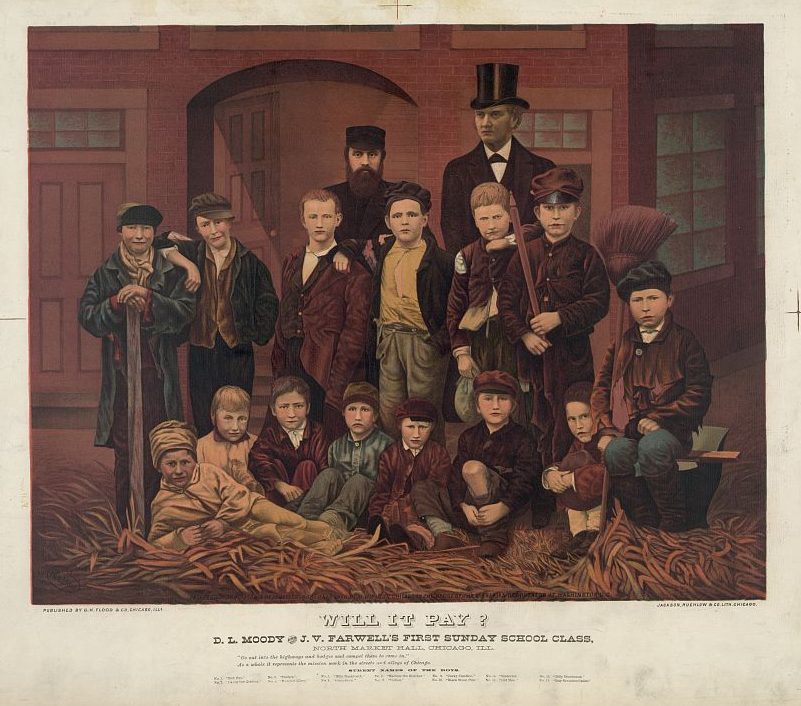

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-03685.

Even in the context of the antebellum nativism in which anti-Catholicism was a seminal feature, Beecher was sensitive to the potential that his arguments would be dismissed as merely intolerant. Yet religious toleration—or what Beecher calls “charity”—does not require turning a blind eye to potential threats, he argues, for the simple reason that truth can always withstand the strongest scrutiny. Beecher’s anti-Catholic rhetoric raises several important questions about the possible limits on religious liberty and the proper course of action for a republican nation to take when faced with a potential incompatibility between the principles undergirding its political order and the teachings of a particular religion.

A Plea for the West

…It is certain that the glorious things spoken of the church and of the world, as affected by her prosperity, cannot come to pass under the existing civil organization of the nations. Such a state of society as is predicted to pervade the earth, cannot exist under an arbitrary despotism, and the predominance of feudal institutions and usages. Of course, it is predicted that revolutions and distress of nations will precede the introduction of the peaceful reign of Jesus Christ on the earth. The mountains shall be cast down, and the valleys shall be exalted and he shall “overturn, and overturn, and overturn, till he whose right it is, shall reign King of nations King of saints.”1

It was the opinion of Edwards2 that the millennium would commence in America. When I first encountered this opinion, I thought it chimerical; but all providential developments since, and all the existing signs of the times, lend corroboration to it. But if it is by the march of revolution and civil liberty, that the way of the Lord is to be prepared, where shall the central energy be found, and from what nation shall the renovating power go forth? What nation is blessed with such experimental knowledge of free institutions, with such facilities and resources of communication, obstructed by so few obstacles, as our own? There is not a nation upon earth which, in fifty years, can by all possible reformation place itself in circumstances so favorable as our own for the free, unembarrassed applications of physical effort and pecuniary and moral power to evangelize the world.

But if this nation is, in the providence of God, destined to lead the way in the moral and political emancipation of the world, it is time she understood her high calling, and were [sic] harnessed for the work. For mighty causes, like floods from distant mountains, are rushing with accumulating power, to their consummation of good or evil, and soon our character and destiny will be stereotyped forever.

It is equally plain that the religious and political destiny of our nation is to be decided in the West. There is the territory, and there soon will be the population, the wealth, and the political power. The Atlantic commerce and manufactures may confer always some peculiar advantages on the East. But the West is destined to be the great central power of the nation, and under heaven, must affect powerfully the cause of free institutions and the liberty of the world. …It is equally clear, that the conflict which is to decide the destiny of the West, will be a conflict of institutions for the education of her sons, for purposes of superstition, or evangelical light; of despotism, or liberty.

…The thing required for the civil and religious prosperity of the West, is universal education, and moral culture, by institutions commensurate to that result – the all-pervading influence of schools, and colleges, and seminaries, and pastors, and churches. When the West is well supplied in this respect, though there may be great relative defects, there will be, as we believe, the stamina and the vitality of a perpetual civil and religious prosperity.

By whom shall the work of rearing the literary and religious institutions of the West be done?

Not by the West alone. The West is able to do this great work for herself, – and would do it, provided the exigencies of her condition allowed to her the requisite time. The subject of education is nowhere more appreciated; and no people in the same time ever performed so great a work as has already been performed in the West. Such an extent of forest never fell before the arm of man in forty years, and gave place, as by enchantment, to such an empire of cities, and towns, and villages, and agriculture, and merchandise, and manufactures, and roads, and rapid navigation, and schools, and colleges, and libraries, and literary enterprise, with such a number of pastors and churches, and such a relative amount of religious influence, as has been produced by the spontaneous effort of the religious denominations of the West. The later peopled states of New-England did by no means come as rapidly to the same state of relative, intellectual and moral culture as many portions of the West have already arrived at, in the short period of forty, thirty, and even twenty years.

But this work of self-supply is not completed, and by no human possibility could have been completed by the West, in her past condition. No people ever did, in the first generation, fell the forest, and construct the roads, and rear the dwellings and public edifices, and provide the competent supply of schools and literary institutions. New-England did not. Her colleges were endowed extensively by foreign munificence, and her churches of the first generation were supplied chiefly from the mother country; and yet the colonists of New-England were few in number, compact in territory, homogeneous in origin, language, manners, and doctrines; and were coerced to unity by common perils and necessities; and could be acted upon by immediate legislation; and could wait also for their institutions to grow with their growth and strengthen with their strength. But the population of the great West is not so, but is assembled from all the states of the Union, and from all the nations of Europe, and is rushing in like the waters of the flood, demanding for its moral preservation the immediate and universal action of those institutions which discipline the mind, and arm the conscience and the heart. And so various are the opinions and habits, and so recent and imperfect is the acquaintance, and so sparse are the settlements of the West, that no homogeneous public sentiment can be formed to legislate immediately into being the requisite institutions. And yet they are all needed immediately, in their utmost perfection and power. A nation is being “born in a day,” and all the nurture of schools and literary institutions is needed, constantly and universally, to rear it up to a glorious and unperverted manhood.

It is no implication of the West, that in a single generation, she has not completed this work. In the circumstances of her condition she could not do it; and had it been done, we should believe that a miraculous, and not a human power had done it.

Who then, shall co-operate with our brethren of the West, for the consummation of this work so auspiciously begun? Shall the South be invoked? The South have difficulties of their own to encounter, and cannot do it; and the middle states have too much of the same work to do, to volunteer their aid abroad.

Whence, then, shall the aid come, but from those portions of the Union where the work of rearing these institutions has been most nearly accomplished, and their blessings most eminently enjoyed. And by whom, but by those who in their infancy were aided; and who, having freely received, are now called upon freely to give, and who, by a hard soil and habits of industry and economy, and by experience are qualified to endure hardness as good soldiers and pioneers in this great work? And be assured that those who go to the West with unostentatious benevolence, to identify themselves with the people and interests of that vast community, will be adopted with a warm heart and an unwavering right hand of fellowship.

…Experience has evinced, that schools and popular education, in their best estate, go not far beyond the suburbs of the city of God. All attempts to legislate prosperous colleges and schools into being without the intervening influence of religious education and moral principle, and habits of intellectual culture which spring up in alliance with evangelical institutions, have failed. Schools wane, invariably, in those towns where the evangelical ministry is neglected, and the Sabbath is profaned, and the tavern supplants the worship of God. Thrift and knowledge in such places go out, while vice and irreligion come in.

But the ministry is a central luminary in each sphere, and soon sends out schools and seminaries as its satellites by the hands of sons and daughters of its own training. A land supplied with able and faithful ministers, will of course be filled with schools, academies, libraries, colleges, and all the apparatus for the perpetuity of republican institutions. It always has been so – it always will be.

But the ministry for the West must be educated at the West. The demands on the East, for herself and for pagan lands, forbid the East ever to supply our wants. Nor is it necessary. For the Spirit of God is with the churches of the West, and pious and talented young men are there in great numbers, willing, desiring, impatient to consecrate themselves to the glorious work. If we possessed the accommodations and the funds, we might easily send out a hundred ministers a year, a thousand ministers in ten years, around each of whom schools would arise, and instructors multiply, and churches spring up, and revivals extend, and all the elements of civil and religious prosperity abound.

[At this point in the pamphlet, Beecher shifts his focus to the changing demographics of the West. He refers repeatedly to the rising number of Catholic immigrants in the region as a threat to its American character, due to their “ignorant” and “corrupting” influence.]…It [Beecher’s concern with Catholic influence] is nothing but a controversy about religion, it is said – a thing which has nothing to do with the liberty and prosperity of nations, and the sooner it is banished from the world the better.

As well might it be insisted that the sun has no influence on the solar system, or the moon on the tides. In all ages, religion, of some kind, has been the former of man’s character and the mainspring of his action. It has done more to fill up the eventful page of history, than all moral causes beside. It has been the great agitator or tranquilizer of nations, the orb of darkness or of light to the world, the fountain of purity or pollution, the mighty power of riveting or bursting the chains of men. Atheists may rage and blaspheme, but they cannot expel religion of some kind from the world. Their epidemic madness, like the volcano, may at times break out, and obscure the sun, and turn the moon into blood, and extend from nation to nation the cup of God’s displeasure, covering the earth with the slain and the fragments of demolished institutions. But it can reconstruct nothing. It must be temporary, or it would empty the earth of its inhabitants. It will be temporary, because so bright are the evidences of a superior power, and so frail and full of sorrow are men, and so guilty and full of fears, that if Christianity does not guide them to the true God and Jesus Christ, superstition will send them to the altars of demons.

But it is a contest, it is said, about religion – and religion and politics have no sort of connection. Let the religionists fight their own battles; only keep the church and state apart, and there is no danger.

It [what will happen in the west as the number of Catholics increases] is a union of church and state, which we fear, and to prevent which we lift up our voice: a union which never existed without corrupting the church and enslaving the people, by making the ministry independent of them and dependent on the state, and to a great extent a sinecure aristocracy of indolence and secular ambition, auxiliary to the throne and inimical to liberty. No treason against our free institutions would be more fatal than a union of church and state; none, when perceived, would bring on itself a more overwhelming public indignation, and which all Protestant denominations would resist with more loathing and abhorrence.

…But in republics the temptation and the facilities of courting an alliance with church power may be as great as in governments of less fluctuation. Amid the competitions of party and the struggles of ambition, it is scarcely possible that the clergy of a large denomination should be able to give a direction to the suffrage of their whole people, and not become for the time being the most favored denomination, and in balanced elections the dominant sect, whose influence in times of discontent may perpetuate power against the unbiased verdict of public opinion. The free circulation of the blood is not more essential to bodily health, than the easy, unobstructed movement of public sentiment in a republic. All combinations to forestall and baffle its movements tend to the destruction of liberty. Its fluctuations are indeed an evil; but the power to arrest its fluctuations and chain it down is despotism; and when it is accomplished by the bribed alliance of ecclesiastical influence in the control of suffrage, it appears in its most hateful and alarming form. It is true, that the discovery might produce a reaction, and sweep away the ecclesiastical intermeddlers. But in political crises, calamities may be inflicted in a day, which ages cannot repair; and who can tell, when the time comes, whether the power will be too strong for the fetters, or the fetters for the power? For none but desperate men will employ such measures for the acquisition of power; and when desperate men have gained power they will not relinquish it without a struggle.

…”But why so much excitement about the Catholic religion? Is not one religion just as good as another?”

There are some who think that Calvinism is not quite as good a religion as some others. I have heard it denounced as a severe, unsocial, self-righteous, uncharitable, exclusive, prosecuting system—“dealing damnation round the land”—compassing sea and land to make proselytes, and forming conspiracies to overturn the liberties of the nation by an unhallowed union of church and state. There have been those, too, who have thought it neither meddlesome nor persecution to investigate the facts in the case, and scan the republican tendencies of the Calvinistic system. Though it has always been on the side of liberty in its struggles against arbitrary power; though, through the Puritans, it breathed into the British constitution its most invaluable principles, and laid the foundations of the republican institutions of our nation, and felled the forests, and fought the colonial battles with Canadian Indians and French Catholics, when often our destiny balanced on a pivot and hung upon a hair; and though it wept, and prayed, and fasted, and fought, and suffered through the revolutionary struggle, when there was almost no other creed but the Calvinistic in the land; still it is the opinion of many, that its well-doings of the past should not invest the system with implicit confidence, or supersede the scrutiny of its republican tendencies. They do not think themselves required to let Calvinists alone; and why should they? We do not ask to be let alone, nor cry persecution when our creed or conduct is analyzed. We are not annoyed by scrutiny; we seek no concealment. We court investigation of our past history, and of all the tendencies of the doctrines and doings of the friends of the Reformation; and why should the Catholic religion be exempted from scrutiny? Has it disclosed more vigorous republican tendencies? Has it done more to enlighten the intellect, to purify the morals, and sanctify the hearts of men, and fit them for self-government? Has it fought more frequently or successfully the battles of liberty against despotism? or done more to enlighten the intellect, purify the morals, and sanctify the heart of the world, and prepare it for universal liberty?

I protest against that unlimited abuse with which it is thought quite proper to round off declamatory periods against the religion of those who fought the battles of the reformation and the battles of the revolution, and that sensitiveness and liberality which would shield from animadversion and spread the mantle of charity over a religion which never prospered but in alliance with despotic governments, has always been and still is the inflexible enemy of liberty of conscience and free inquiry, and at this moment is the main stay of the battle against republican institutions.

A despotic government and despotic religion may not be able to endure free inquiry, but a republic and religious liberty CANNOT EXIST WITHOUT IT. Where force is withdrawn, and millions are associated for self-government, the complex mass of opinions and interests can be reduced to system and order only by the collision and resolution of intellectual and moral forces.

To lay the ban of a fastidious charity on religious free inquiry, would terminate in unthinking apathy and the intellectual stagnation of the dark ages.

…It is an anti-republican charity, then, which would shield the Catholics, or any other religious denomination, from the animadversion of impartial criticism. Denominations, as really as books, are public property, and demand and are benefited by criticism. And if ever the Catholic religion is liberalized and assimilated to our institutions, it must be done, not by a sickly sentimentalism screening it from animadversion, but by subjecting it to the tug of controversy, and turning upon it the searching inspection of the public eye, and compelling it, like all other religions among us, to pass the ordeal of an enlightened public sentiment.

…Catholic powers are determined to take advantage of our halting by thrusting in professional instructors and underbidding us in the cheapness of education – calculating that for a morsel of meat we shall sell our birth-right. Americans, republicans, Christians, can you, will you, for a moment, permit your free institutions, blood bought, to be placed in jeopardy, for want of the requisite intellectual and moral culture?

One thing more only demands attention, and that is the extension of such intellectual culture, and evangelical light to the Catholic population, as will supersede implicit confidence, and enable and incline them to read, and think, and act for themselves. They are not to be regarded as conspirators against our liberties; their system commits its designs and higher movements, like the control of an army, to a few governing minds, while the body of the people may be occupied in their execution, unconscious of their tendency. I am aware of the difficulty of access, but kindness and perseverance can accomplish anything, and wherever the urgency of the necessity shall put in requisition the benevolent energy of this Christian nation – the work under the auspices of heaven will be done.

It is a cheering fact, also, that the nation is waking up – a blind and indiscriminate charity is giving place to sober observation, and a Christian feeling and language towards Catholics is taking the place of that which was petulant, and exceptionable. There is rapidly extending a just estimate of danger. Multitudes who till recently regarded all notices of alarm as without foundation, are now beginning to view the subject correctly, both in respect to the reality of the danger, and the means which are necessary to avert it, and both the religious and the political papers are beginning to lay aside the language of asperity and to speak the words of truth and soberness. Under such auspices we commit the subject to the guardianship of heaven, and the intelligent instrumentality of our beloved country.

Study Questions...

View All

What is the connection between religion, education, and liberty for Beecher? Why does he fear Catholicism, and what does it tell us about the types of religions that he believes will be compatible or incompatible with the American way of life?

Compare...

How is Beecher’s vision of American expansion related to Winthrop’s “city on a hill”? How does it relate to the Northwest Ordinance or Adams’ Speech on Independence Day? In what ways is Beecher’s understanding of religion and liberty similar to or different from that presented by Obama?

Notes

1 A popular quotation linking the prophecy in Ezekiel 21:27 to the second coming of Christ.

2 Jonathan Edwards, New England minister (see document 3), has often been credited with this position, although the nature of Edwards’ millennialism has been the subject of significant scholarly debate. See John F. Wilson, “History, Redemption, and the Millennium,” in Jonathan Edwards and the American Experience, Nathan O. Hatch and Harry S. Stout, eds. (Oxford, 1988), 131-141.