Lane Theological Seminary

Cincinnati, Ohio

1829 - 1932

Lane Theological Seminary was founded by the Presbyterian church during the wave of evangelical revivals known as the Second Great Awakening with the express purpose of educating pastors to serve the growing population of the old Northwest Territory.

View of Lane Theological Seminary from the General Catalogue. 1829-1899.

A Seminary for the West

As America expanded Westward in the early nineteenth century, so too, did her religious institutions. Members of the evangelical wing of the Presbyterian Church decided in the 1820s that establishing a seminary in a western city would make it easier to train and support pastors serving in the developing regions of the nation. The choice of Cincinnati was strategic: as members of the class of 1833 would later explain

[The West] was our expected field; we assembled here, that we might the more accurately learn its character, catch the spirit of the gigantic enterprise, grow up into its genius, appreciate its peculiar wants, and be thus qualified by practical skill, no less than by theological erudition, to wield the weapons of truth. (“Statement of Reasons,” From The Liberator, vol. 5, no. 2, Jan. 10, 1835, pp. [5]-6)

The nation’s most significant inland city, Cincinnati’s location on the Ohio River made it a center of commerce and communication, the pivot point between not only Eastern and Western States, but between North and South as well. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the school quickly became the site of a major rift in American Protestantism over the issue of slavery.

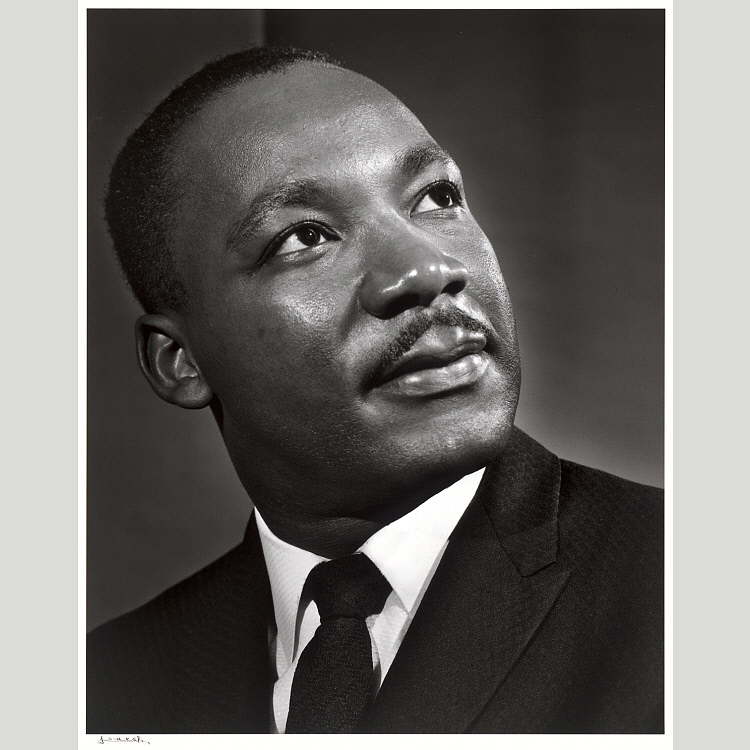

Portrait of Lyman Beecher, between 1855-1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-cwpbh-02529.

The college trustees recruited prominent New England preacher Lyman Beecher to serve as the Seminary’s first president in 1832. Beecher–an evangelical who combined theology with activism–encouraged the students to reflect on the application of Christianity to the serious social and political problems of their time, including slavery. Although some of the students came from Southern families, even they tended to be view the institution of slavery as an evil in need of reform: the question for the Lane student body was not whether slavery should be brought to an end, but how.

Up to this point in the nation’s history, anti-slavery advocates had largely taken one of two positions: gradual emancipation, or colonization. As the nineteenth century wore on, the question of slavery weighed ever more heavily upon the conscience of Americans in the northern and western states, some reformers like William Lloyd Garrison began to demand the immediate end of slavery in the United States. These radical abolitionists spoke with a sense of moral imperative: with fiery rhetoric, they denounced not only the evils of slavery, but also their more moderate counterparts in the anti-slavery movement as little better than co-conspirators with slaveholders.

Abolition Debates of 1834

As members of the evangelical wing of the Presbyterian Church, the students at Lane were eager to consider the ways their faith might be applied to the social and political concerns of their time–chief among them, slavery. The seminarians organized an eighteen-day event to consider two central questions:

“Ought the people of the slaveholding States to abolish Slavery immediately?”

“Are the doctrines, tendencies, and measures of the American Colonization Society, and the influence of its principal supporters, such as render it worthy of the patronage of the Christian public?”

Representatives from the student body who had first-hand experience with slavery spoke for nine evenings on each question. By the end of the debates, it was clear that the majority of the students had not only reached the opinion that colonization was un-Christian, but also that immediate abolition was the only possible position compatible with Christian beliefs. The formed an anti-slavery society with the goal of “the immediate emancipation of the whole colored race within the United States: The emancipation of the slave from the oppression of the master, the emancipation of the free colored man from the oppression of public sentiment, and the elevation of both to an intellectual, moral, and political equality with the whites.” To achieve these ends, the students vowed to use their theological training to help shift public opinion on the issue, as well as to improve the condition of the black population in their midst.

The students not only “published facts, arguments, remonstrances and appeals” they also “threw [them]selves into the neglected mass of colored population in the city of Cincinnati, and that we might lead it up to the light of the sun, established Sabbath day and evening schools, lyceums, a circulating library, &c..” [1] The radicalization of the student body unnerved the local population, and the school’s governing board responded to their complaints by censoring all anti-slavery speech and activity on the grounds that it was unrelated to the scholarly work of the institution. Nearly forty members of the student body left in response to the Board’s actions: these “Lane Rebels” eventually found a home at Oberlin College, where they contributed to its reputation as an institution at the forefront of social and cultural reform.

The Aftermath: Two Visions of Freedom and Religion

In the immediate aftermath of the controversy over the abolition debates, two strikingly different visions of the relationship between religion and freedom emerged. To the students and their supporters, the Board’s actions were a clear infringement upon their natural right to free inquiry. In a lengthy statement published in The Liberator, the Rebels explained their decision to leave the seminary.

Preamble and constitution of the anti-slavery society of Lane Seminary. [c. 1834]. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.24800600/.

We believe free discussion to be the duty of every rational being. It is the acting out of the command ‘prove all things.’ It is inquiry after immutable truth, whether embodied in the word, or hid in the works of God, or branching out through the relations and duties of man. We bound to conduct this search, wherever it may lead, and to adopt the conclusions to which it may bring us. And, whereas, the single object of ascertaining truth is to learn how to act, we are bound to do at once whatever truth dictates to be done. This duty of discussion and action is not conferred by human authority, and we have no licenseto resign it upon entering into any association, literary or political. Free discussion being a duty, is consequently a right, and as such, is inherent and inalienable. It is our right. It was before we entered Lane Seminary: privileges we might and did relinquish; advantages might and did receive. But this right the institution ‘could neither give nor take away.’

… If it be objected that such a system of government is liable to abuse by students, we answer, be it so. Moral agency is abused by every sinner. Liberty is liable to abuse, and so is religion. Heaven was abused by devils, and Paradise was prostituted by Adam. The best principles, as well as the best things, are most liable to abuse. But there is a remedy; the same that God adopted with the fallen angels and our first parent, —Expulsion. We know of no other. Inhibition of free discussion is ruin, not remedy.[2]

Thus, what happened at Lane Seminary is often cited as a landmark in the development of the modern conception of academic freedom–a concept that in its origins, draws explicitly upon a Christian understanding of freedom of conscience and religious exercise.

Meanwhile, Beecher sought to use his position as the head of the seminary to promote his vision of a theologically conservative and moderately reform-minded Protestantism as the key to national peace and prosperity. Ironically, in A Plea for the West, Beecher argued that popular support of mainline protestant educational institutions (like Lane) was the only way order to secure the “religious and political destiny” of the nation. National identity–threatened by radical Protestantism of the sort represented by the Lane Rebels–was equally threatened by the growing influence of Catholicism in the United States, with its historic associations with monarchical and even despotic regimes.