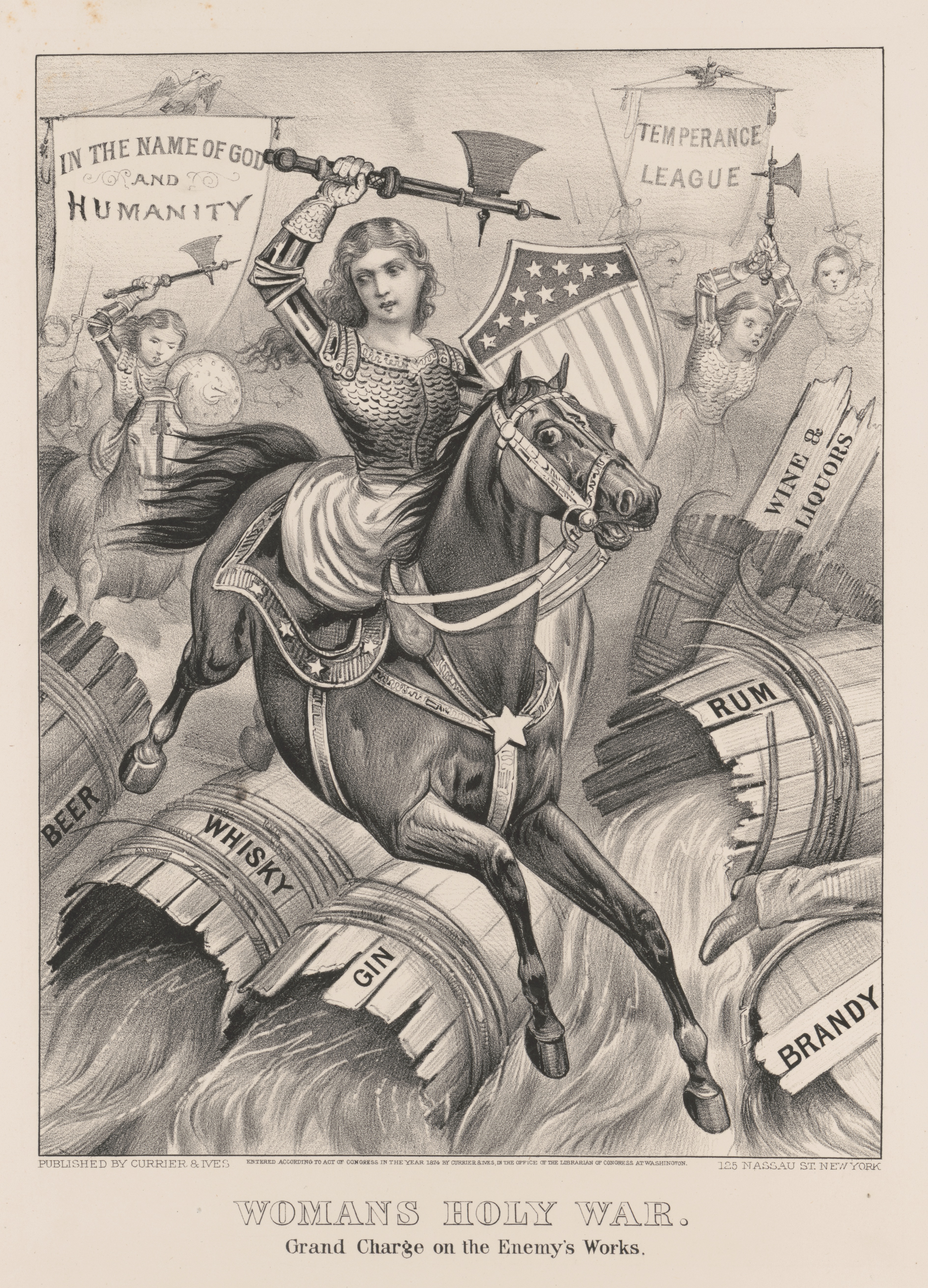

Woman’s Holy War

Currier and Ives

c. 1874

In the late nineteenth century, public opposition to the excessive use of strong drink became increasingly strident, even violent.

Detail

In the center of the image, a beautiful yet fierce young woman smashes through a pile of barrels containing various liquors, splitting them open and spilling their contents wildly. Her steed–whose wide eyes suggest the fevered pitch of the battle in which our heroine is engaged–is dark. This is, perhaps, an allusion to the proverbial “dark horse,” the candidate for office who succeeds despite being seemingly ill-suited to the job. By portraying the women of the temperance league (referenced in the banner, top right) as dark-horsed crusaders, Currier and Ives underscore the improbability of the movement’s success: it was, after all, largely led and supported by women, a class of citizens sans suffrage in the 1870s.

Detail

In equipping our heroine with a shield boldly blazoned with the stars and stripes, however, the artists also suggest that her cause is not only just and holy, but patriotic. She is an American woman (note her resemblance to 19th century portrayals of the feminization of the national identity in the form of Columbia seen here as depicted by Thomas Nast in an 1865 Harper’s Weekly illustration).

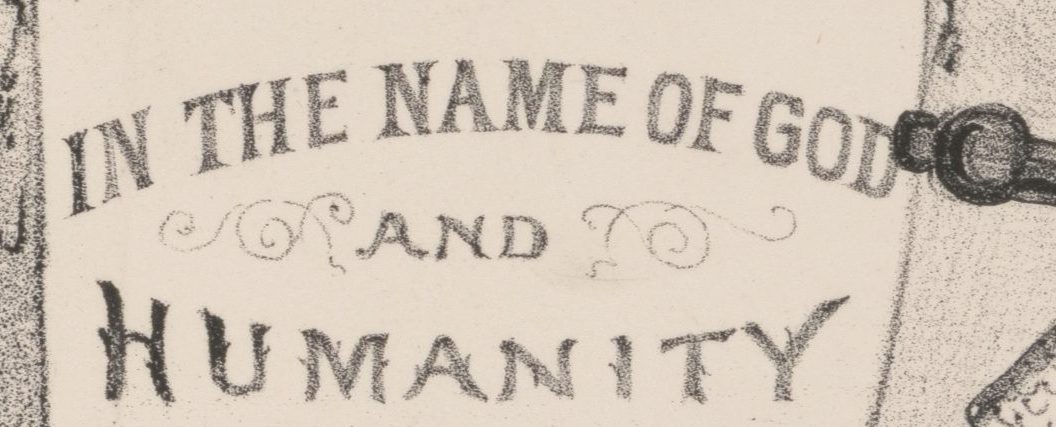

Detail

Her comrades in arms are equally fierce, and whatever they may lack in physical strength, they come to the battle armed with a sense of divine purpose: the banner to the left in the background reads “In the Name of God and Humanity,” reminding the viewer that temperance advocates were often religiously motivated. Excessive consumption of alcohol was linked to a litany of other vices, and temperance advocates argued that eliminating the production and sale of hard liquor would have an immediate positive effect on public morals.

Although the ill effects of intemperate masculinity on wives and children in the form of violence or neglect were frequently reported by temperance reformers, in this image, the emphasis is on the universal and social benefits of temperance — the women march not on their own behalf exclusively, but for their menfolk too, for “humanity” as a whole.

Detail

Finally, note the gentleman’s leg sticking out of the right edge of the foreground; whatever the ladies’ intent in bringing their crusade in his direction, he has fled the scene to parts unknown. This leaves the viewer in doubt that “humanity” are very desirous of the reforms being urged upon them, and suggests that the temperance reformers, although well-intentioned, might in the end, be misguided in their tactics, if not their mission.