Christianity and Slavery: The Moravians of North Carolina

1753-1858

The story of the enslaved people admitted to the fellowship of the Moravian community in Salem, North Carolina, illustrates the contradictions inherent in a Southern culture identifying as Christian and reliant on slave labor.

The use of slave labor in the American South presented—not surprisingly—ethical challenges to those Christians committed to preaching the gospel to all. In his groundbreaking study, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South (Oxford, 1978; updated 2004), Albert J. Raboteau summarized the contradictions inherent in efforts to evangelize slaves:

There was something peculiar about the way African slaves were evangelized in America. Traditionally, “preaching the gospel to all nations” meant that the Christian disciple was sent out with the gospel to the pagans. In America the reverse was the case: the pagan slave was brought to a Christian disciple who was frequently reluctant to instruct him in the gospel. The irony of that situation bore practical implications for the interrelationships between master, missionary, and slave. (p. 120)

The initial reluctance of colonial slaveholders to teach the gospel to those they held as slaves arose from their instinctive feeling that baptizing a slave meant acknowledging his humanity, and would oblige them to free him. For their part, Africans newly arrived in America after the traumatic Middle Passage were seldom interested in adopting the white man’s faith. Still, colonial divines like Cotton Mather thought it incumbent upon slaveholders to bring their slaves into the faith and thereby assure the salvation of their souls.

Gospel Message of Great Awakening Reaches those Enslaved in North America

George Whitefield, mezzotint by John Greenwood (1769) after painting by Nathaniel Hone. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, NPG.75.77.

During the “Great Awakening” which swept the colonies in the 1730s and 1740s (recurring in local revivals during the rest of the 18th century), missionaries who spread the gospel message often found enslaved people receptive. Because evangelists like Whitefield and Wesley presented the gospel in simple, yet emotive language (rather than in the more theologically technical diction of the Anglican liturgy and catechism), enslaved people with limited education could grasp it more easily. Raboteau writes that the would-be converts often expected that baptism would result in a change of their status. After slaveholders began to complain of slaves who balked at work after baptism, evangelists strove to squelch such expectations. Raboteau’s book details the resultant complex process in which African Americans gave the faith their own distinctive style and emphasis—in part by infusing it with cultural attitudes and practices brought from Africa and in part by focusing on a tenet of the faith that marginalized people have always grasped more readily than Christians in more fortunate circumstances: that God, in the person of Jesus Christ, redeemed humanity by suffering as humanity suffers.

The Moravians of Salem, North Carolina

In the context of this overall pattern, the story of the enslaved people admitted to the fellowship of the Moravian community in Salem, North Carolina provides a poignant example. In his study, A Separate Canaan: The Making of an Afro-Moravian World in North Carolina, 1763–1840, Jon J. Sensbach examines the motives of African Americans who sought and were granted membership in the Moravian fellowship. He shows that many of these converts did expect to shed their slave status. The disappointment of these hopes among black Moravians occurred more gradually than in the case of many other slave groups.

Moravians were active evangelists among the enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and among Native Americans, particularly in the area around Bethlehem, PA. This drawing shows a missionary baptizing members of the Munsee-Delaware tribe. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

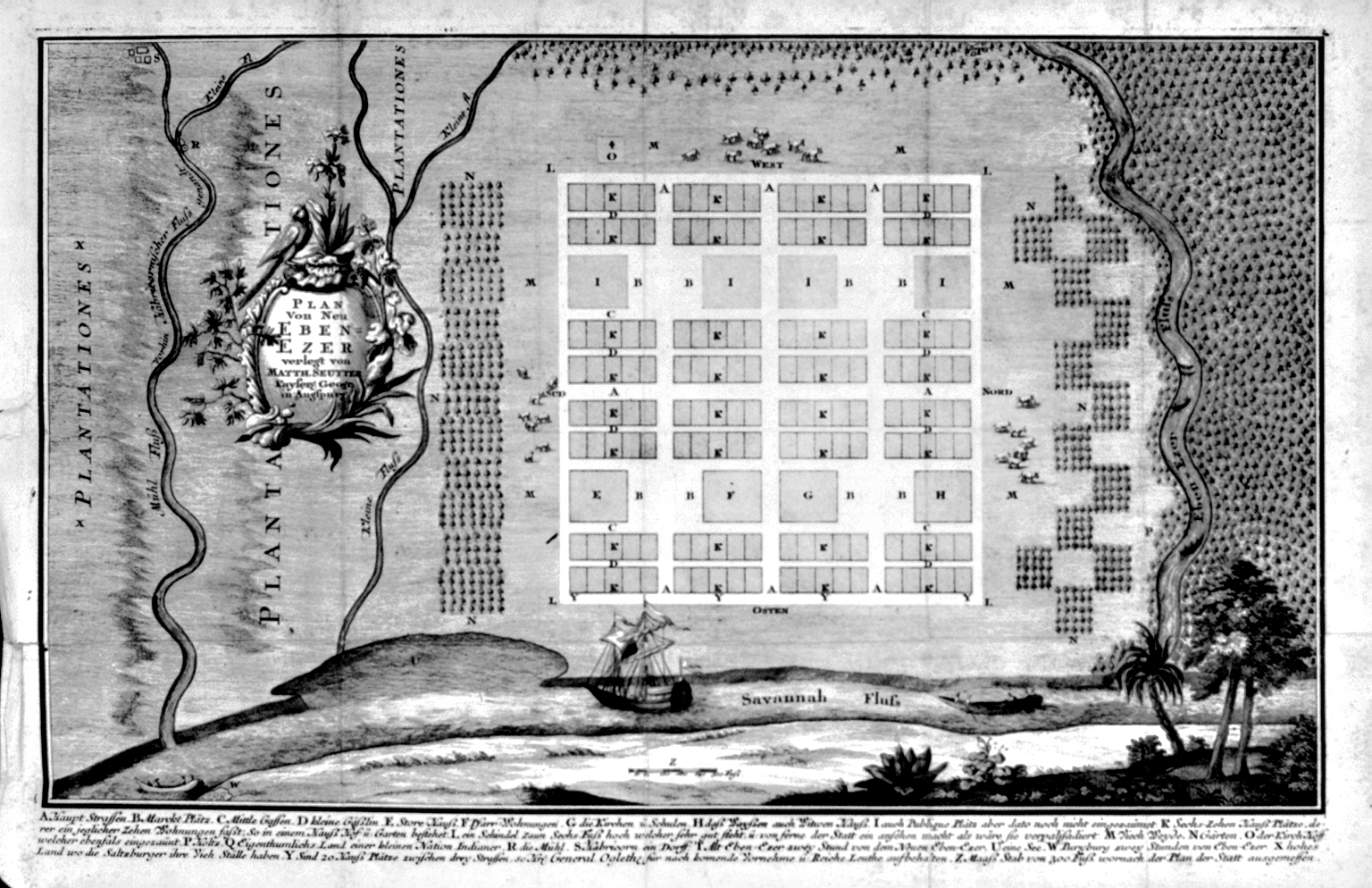

The Moravians, who called themselves the Unity of Brethren, were theologically descended from Jan Hus’s 15th century attempt to reform Bohemian Catholicism yet related in other ways to the pietistic strain in Lutheranism. After settling in Pennsylvania in 1741, they sent small groups to found settlements elsewhere in the British colonies. A group who travelled to North Carolina in 1753 bought a tract of land in the piedmont (in the area of present-day Winston Salem) and started building settlements. They planned for one large “Congregation Town” in the middle of the tract that would be organized in a semi-collective fashion and embody as completely as possible their social ideals.

The “Home” Moravian Church in Salem was organized in 1771. This brick structure, still in use, was consecrated in 1800. Photo By Ellen Tucker.

In this settlement, Salem, the church owned all land, and individuals leased the land for their homes and businesses. Adolescent Moravians were educated in gender-segregated communal homes called choirs, where they shared worship-centered social activities and were assigned and apprenticed to the various crafts and professions the community required. Before transitioning from this apprenticeship into independent family units, their marriages had to be approved by the ruling council of elders. Educated in this communal way, Moravians were conditioned to a uniform moral code and a shared worship practice that emphasized simplicity and the fellowship of all believers. Those admitted to their communion shared a “kiss of peace” signifying their spiritual equality. Still, all were held accountable to the needs of the community and the decisions of the elders.

The Moravians Become Slaveholders

The Moravians adopted the Southern slave culture somewhat reluctantly. They needed a large labor force to execute their ambitious building projects while attending to basic food-production needs. Finding hired white labor both expensive and socially problematic (because the Anglo-Americans they hired did not share their religion and moral ideals), they began hiring the slaves of neighboring settlers. Such labor came at less than half the cost of the hired white labor, and the Moravians at first found the enslave Africans more tractable. When some of those hired began lobbying to be purchased by the Moravians, so that, as they said, they would have the opportunity to come to know Christ, the Moravians saw this as an opportunity to “solve labor shortages while preserving community morals,” Sensbach writes (p. 65). Like all property in the community, the enslaved people would belong to the community as a whole, preventing any single family from enriching themselves through trading in slaves. Enslaved persons who converted to the faith would share the community’s moral views and behavior.

Conflicting Expectations of Black and White Brethren

Anna Maria Samuel was admitted to membership in the Moravian Church in 1793 at the age of eleven. She became part of the Older Girls Choir, moving into the Sisters House on Salem square (Photo of an exhibit in Historic Old Salem).

In the beginning, Moravians did not assign to slaves work that they themselves were unwilling to do, and they sometimes gave positions of significant responsibility to enslaved persons who had skills that white brethren lacked. Yet those who were enslaved often claimed this rough social parity in a way that surprised and angered the Moravians. This resulted in punishments that surprised and angered the enslaved. A enslaved man’s joking familiarity with Moravian youth might rebound on him in a beating. Other aspects of life with the Moravians seemed unfair. The conversion process involved a series of steps that had to be confirmed by the Moravian elders’ use of the Old Testament-based practice of drawing lots to determine God’s will. Because of this, some proselytes’ request to be confirmed to membership would be frustrated for months or years, even though the would-be converts were dutifully undergoing Christian instruction.

Some enslaved people, after being admitted to full communion with the Moravians, felt the injustice of their slave status more keenly and began challenging it, either in attitudes the Moravians thought “ungrateful” or in clandestine behavior, like stealing community property to engage in secret trading. (Moravians were not allowed to engage in any trade with outsiders that had not been planned by the elders for the entire community’s benefit). During the American Revolution, enslaved people heard news of British commander Cornwallis’ promise to emancipate those who fled to his lines. Sensbach argues that instances of runaways during this time were probably motivated by this news.

Despite the Moravian preference for simplicity, instrumental music was an important part of Moravian worship. Anna Maria Samuel’s three brothers–Christian, John, and Jacob–played classical violin for the black congregation.

As the 18thcentury drew to a close, African Americans asking for membership in the Moravian community seem to have had more modest expectations. Life within the community, where they were spiritual if not social equals, might insulate them from some of the harshness of slave life outside. A real need for “spiritual anchoring” in a world where black servants had been separated from their own traditional spiritual practices, and were often separated from family members, also operated. Finally, the core message of Christianity, especially as preached by the Moravians, meant that “masters were as sinful as [slaves] themselves,” Sensbach writes. It also meant that, while “mankind had been granted a blanket pardon . . . Christ loved . . . and had died especially to save . . . the enslaved and dispossessed, not in spite of their disinheritedness, but because of it” (105–106).

Declining Commitment to Biracial Fellowship

Yet even as slave expectations of membership became more modest, the commitment of white Moravians to a biracial spiritual fellowship shrank. Younger generations of Moravians, born and raised in the South, were adopting Southern racist attitudes. They raised objections to sharing the kiss of peace at baptism, sharing benches in worship, and admitting black young people into the adolescent choir groups. By 1822 the hostility of some white Moravians was so pronounced that the elders of Salem decided to create a separate worship space for black Moravians. The black congregation would be led by a white minister whose role was, in large part, to preach a version of the faith that emphasized obedience to one’s assigned station in life.

In 1823 a log church was built for the African American community in the Salem area. Today a reconstruction of this church, housing an informative exhibit about slave life in Salem, stands on the original site in Historic Old Salem. Photo by Ellen Tucker.

This development in Salem coincided with the clandestine establishment of African American Methodist and Baptist congregations elsewhere in the South. The African Moravian Church in Salem was one of the first African American congregations to operate openly. As such, it provided a source of community support for its small membership, even despite the white minister who supervised services.

During the first year of the Civil War, a new brick church was built for the black congregation. After the Civil War, its members, now freedmen, helped to organize one of the first schools for African American children in North Carolina. In 1914, the church took the name St. Philips. Membership gradually shrank as congregants were drawn toward churches in the larger African American community with a more vibrant worship style. The church held its last service at this location in 1952. (Photo by Ellen Tucker shows Mr. Bill Cook, a volunteer guide at the St. Philip’s Heritage Center and African American History Museum, whose insights enriched this essay.)

Meanwhile, the communalist spirit of Salem was waning, and white Moravians were rebelling against the rule of elders and the bars to individual property acquisition—including personal ownership of slaves. Between 1856 and 1858, the town officials abolished the lease system, subdivided lots in the town, and began selling them off.

Inside the new brick church (today part of the African American History exhibit at Old Salem), several hundred African Americans gathered on May 21, 1865, to hear a Union cavalry chaplain announce their emancipation.