Ely Parker Reflects on Efforts to Christianize the Indians

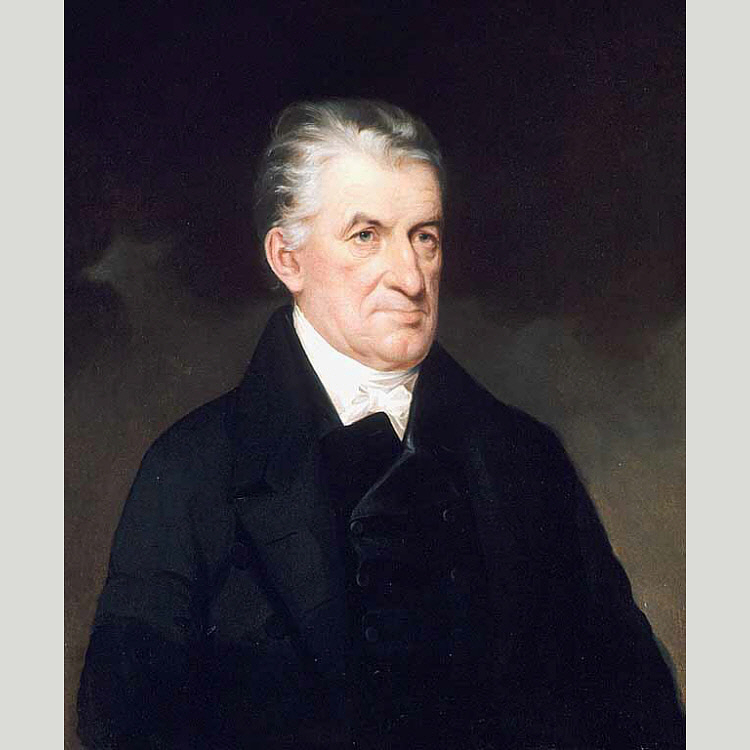

Ely S. Parker

1885

In these letters to a friend, Harriet Converse, who had worked on behalf of the Seneca and was adopted by the tribe as a result (Parker used Converse’s Indian name), Parker reflects on his life, the difficulties of being both a Seneca and an American, and comments on the attempts of religious reformers to aid the Indians.

Dear Gayaneshaoh,

The outpouring of your terrific wrath against certain Christian practices, beliefs and propositions for the amelioration and improvement of certain unchristian people who live on reservations where the English language is not spoken, and where “vice and barbarism” are rampant, was duly received yesterday. The Bishop is right in his reference to the remnants of the Six Nations [Iroquois Confederacy, including the Seneca] being yet “deplorably subject to individual disability, disadvantages and wrong arising from their tribal condition,” in all except the last proposition. The disabilities, disadvantages and wrongs do not result, however, either primarily, consequently or ultimately from their tribal condition and native inheritances, but solely, wholly and absolutely from the unchristian treatment they have always received from Christian white people who speak the English language, who read the English Bible and who are Pharisaically divested of all the elements of vice and barbarism. The tenacity with which the remnants of this people have adhered to their tribal organizations and religious traditions is all that has saved them thus far from inevitable extinguishment. When they abandon their birthright for a mess of Christian pottage they will then cease to be a distinctive people. It is useless though to discuss this question, already prejudiced and predetermined by a granitic Christian hierarchy from whose judgments and decisions there seems to be no appeal. . . .

Dear Gayaneshaoh,

On reading your last note I was greatly amused, – and why? Because what I have written heretofore has been taken literatim et verbatim and a character given me to which I am no more entitled than the man in the moon! I am credited or charged with being “great,” “powerful” and finally crowned as “good”! Oh, my guardian genius, why should I be so burdened with what I am not now and never expect to be! Oh, indeed, would that I could feel a “kindling touch from that pure flame” which a fair and ministering angel would endow me with in the exuberance of prejudiced enthusiasm, and which compels me to sit in sackcloth and ashes. . . .

And why all this commotion of the spirit? Because I am an ideal or a myth and not my real self. I have lost my identity and I look about me in vain for my original being. I never was “great” and never expect to be. I never was “powerful” and would not know how to exercise power were it placed in my hands for use. And that I am “good” or ever dreamed of attaining that blissful condition of being is simply absurd. . . .

All my life I have occupied a false position. As a youth my people voted me a genius and loudly proclaimed that Hawenneyo had destined me to be their savior and gave public thanksgiving for the great blessing they believed had been given them, for unfortunately just at this period they were engaged in an almost endless and nearly hopeless litigated contest for their New York homes and consequently for their very existence.

For many years I was a constant visitor at the State and Federal capitals either seeking legislative relief or in attendance at State and Federal courts. Being only a mere lad, the pale-faced officials with whom I came in contact flattered me and declared that one so young must be extraordinarily endowed to be charged with the conduct of such weighty affairs. I pleased my people in eventually bringing their troubles to a successful and satisfactory termination. I prepared and had approved by the proper authorities a code of laws and rules for the conduct of affairs among themselves and settled them for all time or, for so long as Hawenneyo should let them live.

They saw all this and that it was good. They no longer wanted me nor gave me credit for what had been done. A generation had passed and another grown up since I began to work for them. The young men were confident of their own strength and abilities and needed not the brawny arm of experience to fight their battles for them, nor the wisdom brought about by years of training to guide them any longer. The War of the Rebellion had broken out among the pale-faces, a terrible contest between the slaveholding and non-slaveholding sections of the United States. I had, through the Hon. Wm. H. Seward, personally tendered my services for the non-slaveholding interest. Mr. Seward in short said to me that the struggle in which I wished to assist, was an affair between white men and one in which the Indian was not called on to act. “The fight must be made and settled by the white men alone,” he said. “Go home, cultivate your farm, and we will settle our own troubles without any Indian aid.”

I did go home and planted crops and myself on the farm, sometimes not leaving it for four and six weeks at a time. But the quarrel of the whites was not so easily or quickly settled. It was not a wrangle of boys, but a struggle of giants and the country was being racked to its very foundations.

Then came to me in my forest home a paper bearing the great red seal of the War Department at Washington. It was an officer’s commission in the Army of the United States. The young Indian community had settled in their untutored minds that because I had settled quietly, willingly and unconcernedly in the earning of my living by the sweat of my brow, I was not, therefore, a genius or a man of mind. That they were in truth correct, they did not know, jealousy and envy having prompted the idea and utterance. But now this paper coming from the great Government at Washington offering to confer honors for which I had not served an apprenticeship, nor even asked for, revived among the poor Indians the idea that I was after all a genius and great and powerful, though to them not perceptible. They pleaded with me not to leave them, but to remain as their counsellor, adviser and chief, and that they would be powerless and lost without my presence. They tacitly acknowledged my genius, greatness, and power, and which I did not. When I explained that I was going into the war with a splendid protest of sacrificing my life, as much for their food as for the maintenance of the principles of the Constitution and laws of the United States, and upholding the Union flag in its purity, honor and supremacy over this whole country, they silently and wisely bowed their heads and wept in assent as to the inevitable. I bade them farewell, commended them to the care and protection of Hawenneyo and left them, never expecting to return.

I went from the East to the West and from the West to the East again. They heard of me in great battles and they knew of my association with the great commander of all the Union armies and how I upheld the right arm of his strength, and they said, “How great and powerful is our chief!”

The quarrel between the white men ended and the great commander with his military family settled in Washington, where the great council fire of his nation was annually lighted and blazed in all its glory and fury. As an humble member of this military family I was the envy of many pale-faced subordinate embryo generals who said in whispers, “Parker must be a genius, he is so great and powerful.”

In a few years my military chieftain was made head and front of the whole American people, and in his partiality he placed me at the head of the management of the Indian Affairs of the United States. I was myself an Indian and presumably understood them, their wants and the manipulation of their affairs generally. Then, again went out among the whites and Indians the words, “Parker must be a genius, he is so great and powerful.” The Indians were universally pleased, and they all were willing to be quiet and remain at peace, and were even asking to be taught civilization and Christianity. I stopped and put an end to all wars either among themselves or with their white brothers, and I sent professed Christian teachers among them. But these things did not suit that class of whites who waxed rich and fat from the plundering of the poor Indians, nor were there teacherships enough to give places to all the hungry and impecunious Christians. Then was the cry raised by all who believed themselves injured or unprovided for: “Nay! this Parker is an Indian genius; he is grown too great and powerful; he doth injure our business and taketh the bread from the mouths of our families and the money from out of our pockets, now, therefore, let us write and put him out of power, so that we may feast as heretofore.”

They made their onslaught on my poor innocent head and made the air foul with their malicious and poisonous accusations. They were defeated, but it was no longer a pleasure to discharge patriotic duties in the face of foul slander and abuse. I gave up a thankless position to enjoy my declining days in peace and quiet. But my days are not all peace and quiet. I am pursued by a still small voice constantly echoing, “Thou art a genius, great and powerful,” and even my little cousin, the restless Snipe, has with her strong, piping voice echoed the refrain, “Thou art great, powerful and good.”. . .

Your cousin,

Donehogawa, The Wolf

Notes

Ely S. Parker Ely S. Parker (1828–1895) was a Seneca Indian who studied to be a lawyer, was not allowed to become one because Native Americans at that time were not citizens (in 1924 by act of Congress they became so), then became an engineer, met Ulysses S. Grant while working in Galena, IL, joined the Union Army during the Civil War, and became Grant’s secretary. He was present at Appomattox when Lee surrendered. When Lee saw him he is supposed to have “I am glad to see one real American here,” to which Parker is reported to have responded “We are all Americans.” After the war, Parker served as Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1869–1871). He was accused of misusing funds, resigned, but was later cleared.

Citation

Publications of the Buffalo Historical Society, Volume VIII, ed. Frank H. Severance (Buffalo, NY: Buffalo Historical Society, 1905), 524–527.