The Union Cause as Inspiration for America’s Fight During World War I

Two short stories that merit comparison with Porter’s “Pale Horse Pale Rider” were, like it, not written during World War I but at some distance from it. Willa Cather’s “The Namesake” was published in 1907; Langston Hughes’ “Poor Little Black Fellow” first appeared in 1933. Cather’s story, as the editors of an anthology of American short stories on World War I point out, suggests that pro-war American sentiment was linked to an idealized memory of the Union cause in the Civil War.[1]

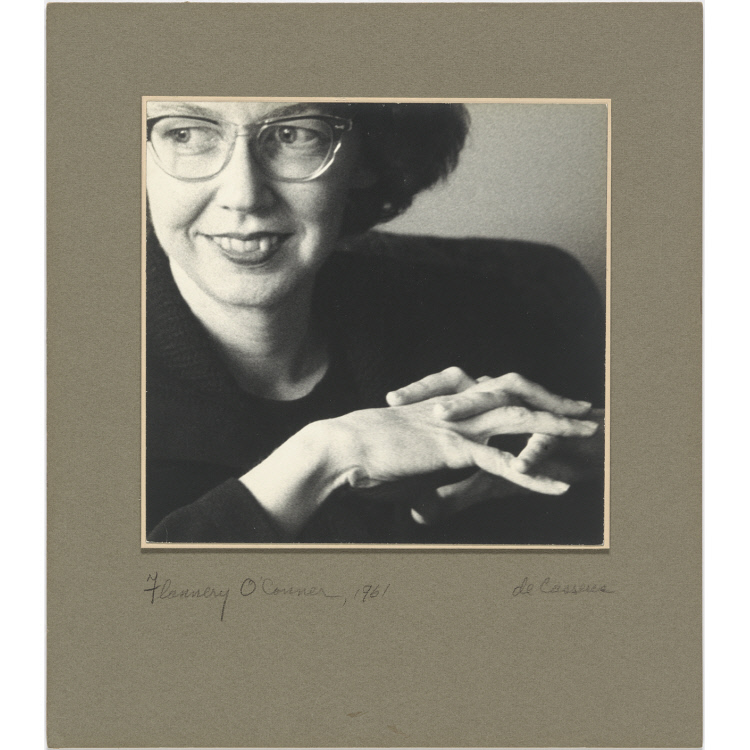

Willa Cather, photo by Carl Van Vechten, 1936. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery.

In the story, an American sculptor living in Paris explains to his fellow ex-patriot artists the inspiration for a work he calls “The Color Sergeant,” depicting “a young soldier running, clutching the folds of a flag, the staff of which had been shot away.” The statue grew from a family story about an ancestor of the artist who joined the Army in 1863, when he was only 14, and died while carrying the flag during battle. In reality, it was not the staff of the flag, but the soldier’s arms, which one by one were shot away. To the artist, these gruesome details only enhance the glory of the boy’s action.

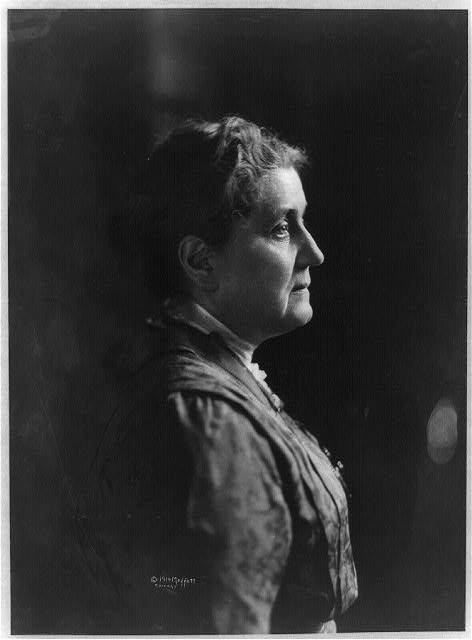

Portrait of Langston Hughes by Winold Reiss, ca. 1925. Gift of W. Tjark Reiss to the National Portrait Gallery.

Hughes tells the story of a young African American orphaned by the war, his father dying in the Argonne and his mother succumbing to pneumonia and grief a few weeks later. The boy’s parents were house servants to an old and wealthy New England family, who decide, in their peculiarly race-conscious fashion, to “adopt” the child as their own. “There was no other way to consider the little colored boy whom they were raising as their own, their very own, except as a Christian duty.” Young Arnold grows up to realize that his upbringing has made him uncomfortable in both the white and black American worlds; but his benefactors cannot understand how their conditional love has left Arnold anything but grateful.

In its use of the Negro spiritual as both title and symbol, Porter’s story points indirectly toward the Civil War as the historical moment in which Americans tried through battle to bring their civic and social life into alignment with their most cherished ideals. Cather and Hughes’ stories make this gesture explicitly. Each story asks whether America is yet ready to shoulder the moral and spiritual responsibilities that such alignment would require.

Detail, Library Of Congress. The stars and stripes, May 24, 1918. 1918. Newspaper. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/20001931/1918-05-24/ed-1/.

Invoking the Union Past for the Soldiers

In their literary works, Cather and Hughes were making popular and explicit the significant symbolic links between the Union cause and the “war to end all wars” that were used to motivate the men serving at the front. This front-page illustration from Stars and Stripes, published on Memorial Day 1918, also invokes “a martyr President, and the memory of the Civil War dead to sanctify the struggles and deaths of American soldiers and war workers,” writes Jonathan H. Ebel in his study, Faith in the Fight: Religion and the American Soldier in the Great War.[2]