The Story of Faith in the Southwest: Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop

Published 90 years ago, Willa Cather’s novel Death Comes for the Archbishop chronicles the cultural transition that took place in the Southwest when what was once Mexico became part of the US. As Cather tells the story, two French Jesuit priests shepherd the people of the Southwest through this changing time.

In 1850 Jean Baptiste Lamy was appointed Bishop Apostolic of the large territory of New Mexico,

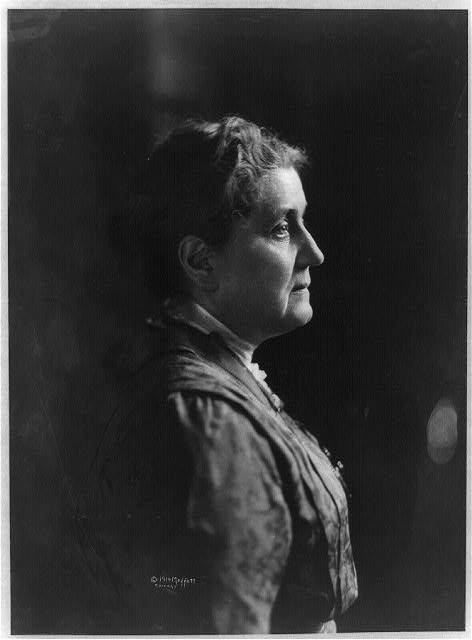

Bishop Joseph Projectus Machebeuf, first Bishop of Denver. He was a close friend of Lamy, accompanying him to Santa Fe but leaving in 1860 to pastor the rough mining communities in Colorado during the gold rush there. Cather portrayed him as Father Joseph Vaillant. Photographed by Charles Bohm between 1860 and 1889.

just annexed due to American victory in the Mexican-American War. Lamy brought with him his close friend Joseph P. Machebeuf, the two having grown up in the same village in the Auvergne, gone to school together, and jointly decided to enter the foreign mission field. Cather fictionalizes these historical figures as Jean Marie Latour, a kindly, cultivated intellectual, and Joseph Vaillant, his outgoing and tireless assistant.

Reclaiming a Catholic Ideal on a Rude Frontier

They have served for a decade as missionaries in Ohio when they are sent to the Southwest, to assert forgotten Papal authority over the inhabitants of a rugged frontier area without well-developed roads that for two centuries has remained largely neglected by Spanish and Mexican central authority. Mexican ranchers and priests have exerted an uneasily divided rule over poorer Mexicans and the Native American population, who themselves are divided among two major tribal groups with different customs, the Pueblo people with their fixed villages and the Navajo, who range with their horses and herds of sheep.

Lamy and Vaillant slowly displace the entrenched Mexican priesthood, many of whom have lived as petty nobles, accumulating private wealth and taking concubines. They bring pastoral care to small remote farms where the faith is still cherished, although marriages have been common-law and the children unbaptized. They encounter suffering and cruelty, sometimes, although not always, managing to rescue the abused.

Two Complementary Personalities

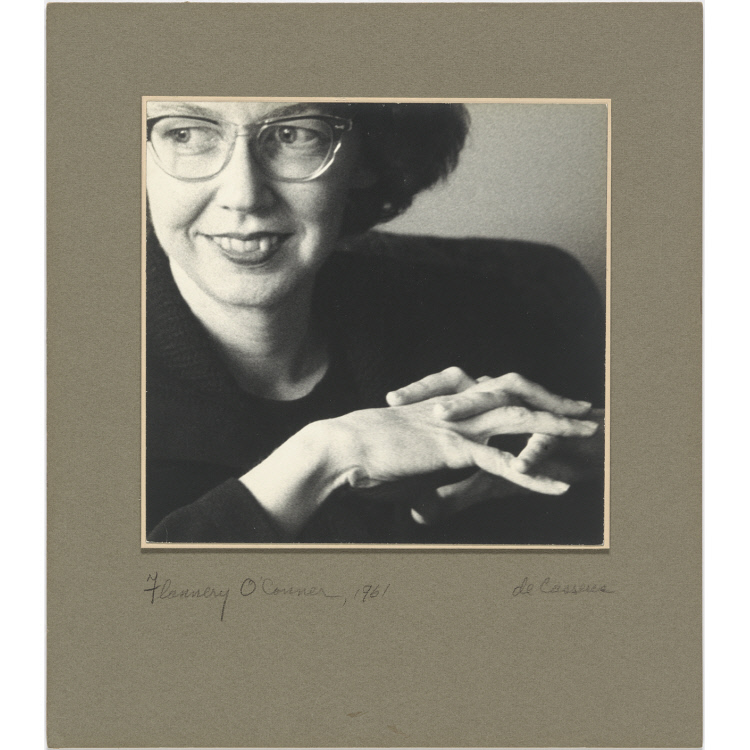

Archbishop Jean Baptiste Lamy, photographed about 1860.

Vaillant becomes the eager, insistent evangelist, traveling out to the roughest and most remote populations, while Lamy makes friends of regional leaders, gaining respect for his integrity and broad-minded understanding of local traditions. Vaillant’s faith is simple, warm and direct, disarming those he meets. Latour’s is strong, yet more philosophical: he seems to represent a fusion of enlightenment progressivism with visionary Christian charity.

Where Vaillant sees miracles in events that allow him to evangelize new areas, Lamy sees the very natural operation of human affection. He tells Vaillant, “Where there is great love there are always miracles. . . . One might almost say that an apparition is human vision corrected by divine love.” Indeed, Latour seems convinced that, in the end, love triumphs in human affairs. He does not hurry to confront a rebellious priest who tyrannizes over all the parishes of northern New Mexico, but he is not intimidated. He “judged that the day of lawless personal power was almost over, even on the frontier, and this figure was to him like something picturesque and impressive, but really impotent, left over from the past.”

Competing Spiritual Histories

The past itself—beside the vividly drawn characters of Latour and Vaillant—is the third dominating presence in the book. Cather organizes the novel around the legends that haunt the austerely beautiful Southwest landscape, a place where ancient stone houses lie semi-hidden in the cliffs and early mission churches with sturdy adobe walls persist despite intermittent neglect. In unhurried, simple prose, she recounts the oral traditions of the multi-faceted Southwestern culture Lamy strives to understand. Cather explained her narrative method in a 1927 letter to the editor of the magazine Commonweal:

Statue of St. Francis of Assisi, in front of the Cathedral Basilica in Santa Fe. Photo by Ken Kopal, Wikimedia Commons, from Flickr, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saint_francis_santa_fe_cathedral.jpg

I had all my life wanted to do something in the style of legend, which is absolutely the reverse of dramatic treatment. . . . In the Golden Legend the martyrdoms of the Saints are no more dwelt upon than are the trivial incidents of their lives; it is as though all human experiences, measured against one supreme spiritual experience, were of about the same importance.[1]

Latour does not perfectly reconcile all he experiences in the Southwest with his providential view of history. He realizes that the Pueblo tribes retain a stubborn pantheistic tradition beneath their seeming compliance with Catholic practice; and he respects the independent culture of the Navajo, deploring their exile to an inhospitable reservation and glad when they are allowed to return to their ancestral land. Still, in the latter, he recognizes divine justice, saying in old age: “I have lived to see two great wrongs righted; I have seen the end of black slavery, and I have seen the Navajos restored to their own country.”

Latour makes his own contribution to the stories of the Southwest by constructing a cathedral. The Saint Francis Cathedral in Santa Fe, a Romanesque structure built of local yellow sandstone, was in fact Archbishop Lamy’s great project. In building it, Cather’s Archbishop sees himself merely continuing a work begun by far more heroic predecessors, the first Franciscan missionaries:

The Spanish Fathers who came up to Zuni, then went north to the Navajos, west to the Hopis, east

The Reredos in the sanctuary of St. Francis, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Photo by Chris Light, Wikimedia Commons.

to all the pueblos scattered between Albuquerque and Taos, they came into a hostile country, carrying little provisionment but their breviary and crucifix. When their mules were stolen by Indians, as often happened, they proceeded on foot, without a change of raiment, without food or water. The old countries were worn to the shape of human life, made into an investiture, a sort of second body, for man. There the wild herbs and the wild fruits of the forest fungi were edible. The streams were sweet water, the trees afforded shade and shelter. But in the alkali deserts the water holes were poisonous, and the vegetation offered nothing to a starving man. . . . Those early missionaries threw themselves naked upon the hard heart of a country that was calculated to try the endurance of giants. . . .

Lamy honors these giants of the past, yet sees all the stories pointing forward. “We build for the future,” he tells Vaillant, who is puzzled that Latour would devote so much thought and energy to a mere edifice.

Cather withholds until the end of the novel the most personal story of the past, an account of how the friends set out together on their life’s mission. Rather than closing the novel with a summation of lives well lived, she highlights the never-finished purpose of the Christian life.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Hermione Lee, Willa Cather: Double Lives (Random House, 2017), p. 265. The Golden Legend was a 13th century collection of hagiographies by the Dominican friar Jacobus de Varagine. His Latin original circulated widely in manuscript and, after the invention of printing, was translated into every major European language. Interest in the book revived in the early 20th century after it was translated into modern French by Teodor de Wyzewa.

Citation

Hermione Lee, Willa Cather: Double Lives (Random House, 2017)