The Methodist Church in America Asserts its Independence: The Christmas Conference of 1784

Ellen Tucker

December 24, 1784 - January 2, 1785

The Methodist Church in America dates its independence to a “Christmas Conference” held 235 years ago in Baltimore, Maryland. This conference was organized and led by Francis Asbury and Thomas Coke.

Methodism, a Pietistic movement within the Anglican Church led by John and Charles Wesley, began to develop an independent identity when it was carried across the Atlantic to the North American colonies. One might suggest several reasons for the growth of the movement among settlers along the western frontier of North America.

A Church that Grew in the Revolutionary Atmosphere of North America

Methodist theology accorded with the growing spirit of self-determination that was drawing the colonists toward claiming political independence. Methodism rejected the Calvinist doctrine of predestination, replacing that understanding of human beings’ ultimate destinies with the Arminian idea of God’s “universal prevenient grace.” Those who chose to accept this grace, repenting and trusting in God’s offer of salvation, could practice a spiritually disciplined way of life, striving for the holiness through which they would attain eternal life.

Methodists used itinerant preachers to spread their message, often self-educated men willing to travel on horseback to settlements not yet served by other Protestant pastors. They organized and retained converts by establishing “bands” who met regularly to examine and encourage each other in their spiritual striving. Many bands drew adherents through family connections and through the unofficial evangelical work of women.

Finally, Methodists criticized the elitist habits and outlook of the gentry class, elevating the ideal of a simple life already lived (by necessity) among those struggling to establish farms along the frontier.

Francis Asbury’s Formative Leadership

The Revd. Francis Asbury, Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States. Painted by J. Paradise; engraved by B. Tanner. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-39570.

Francis Asbury, one of the most energetic of the British-born Methodist itinerant preachers who came to North America just prior to the Revolution, rose to leadership of the evangelical movement through his constant and indefatigable journeys throughout the new colonies. During his 45 years of ministry, he traveled an estimated 130,000 miles on horseback in both North and South, becoming a recognizable face in small communities throughout the nation. He was welcomed because of his obvious sincerity and because he understood and respected the independent spirit of mid-to-late-eighteenth Americans.

At the outset of the Revolution, the Church of England recalled its Anglican pastors from America to England. John Wesley, who disapproved of the American quest for independence, also asked Methodist itinerant preachers to return. Asbury chose to stay. But when Methodists were accused of Loyalist allegiances, Asbury had to go into hiding. After the Revolution, he began traveling again, working to organize conferences among the itinerant preachers of the movement while quietly resisting attempts by John Wesley to continue to control who spoke for Methodism in North America and what routes they traveled.

Wesley wanted to keep Methodism a movement within the Church of England. But Asbury and others realized the movement could not grow unless it gained some autonomy.

Wesley Inadvertently Triggers the Independence of American Methodists

Throughout the Revolution, Methodists in America had been denied the sacraments of baptism and holy communion due to the absence of Anglican pastors. After the Revolution, English bishops were unwilling to ordain any of the self-educated preachers departing to work in America for the nonconforming movement. This left American Methodists still without clergy to deliver the sacraments. So Wesley, ignoring Anglican hierarchy in his own way, decided to send an emissary, Thomas Coke, to America to ordain the lay preachers who were working as Methodist missionaries there. Coke, like Wesley, was Oxford-trained and had gone through normal Anglican ordination.

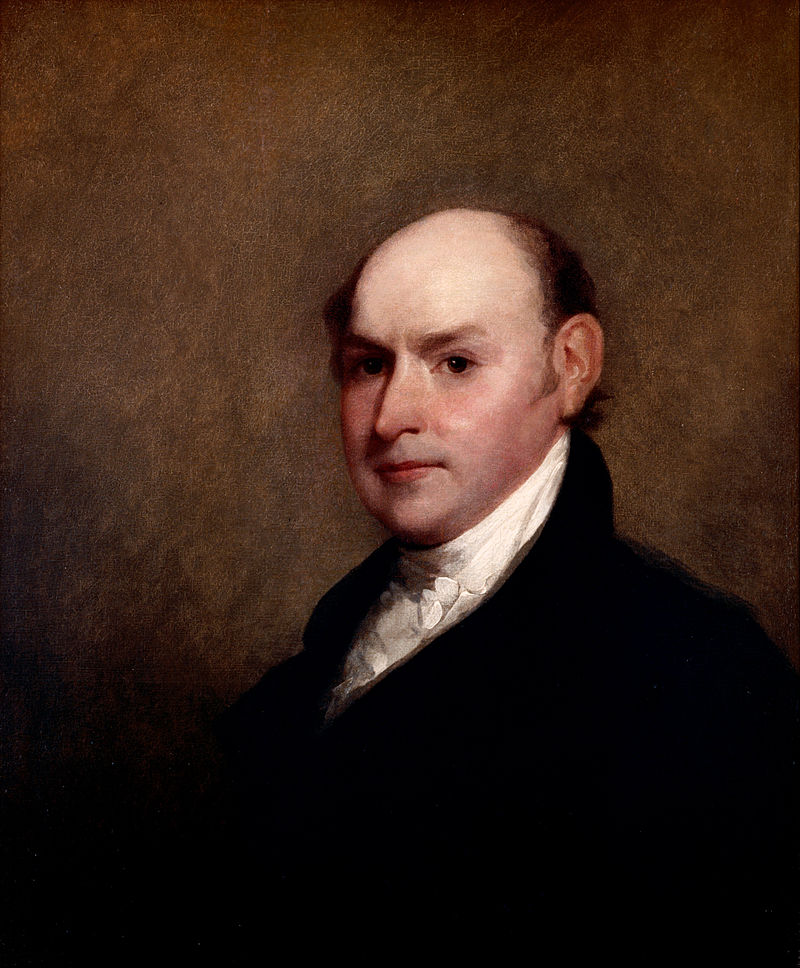

Bishop Thomas Coke (1747-1814)

Coke arrived in North America in 1784, encountering Asbury at a quarterly conference in Delaware and informing him that he had been deputized to ordain preachers in the Methodist movement and to make Asbury and Coke himself co-equal “superintendents” of the entire effort. Asbury cooperated with Coke in a way that established new boundaries for American Methodism. He presented Coke’s announcement to the quarterly conference as if it were a proposal, asking them to endorse it. Having gotten the approval of the Delaware group, Asbury then helped Coke call a meeting of all the itinerant Methodist pastors in America.

The Christmas Conference

This meeting, at Lovely Lane Chapel in Baltimore, would be remembered as the “Christmas Conference,” because it was convened on December 24, 1784 and ran through January 2 of 1785. Asbury persuaded Coke that delegates to the conference should vote to accept Coke and himself as their leaders. Coke complied, first ordaining Asbury on three successive days as deacon, elder (that is, a clergyman), and (after some sort of vote that was not recorded in any minutes) as general superintendent, with Coke, of the American Methodists. The group of 81 delegates also voted to constitute themselves as the Methodist Episcopal Church, a new denomination, tacitly independent of the Church of England.

Asbury thus helped to engineer the independence of American Methodists from the Anglican Church, without announcing any sharp break with Wesley’s overall leadership. The Christmas Conference accepted Wesley’s design for the liturgy, hymnbook, and government of the church, even though it established a precedent of making decisions after debate by majority vote—rather than quiescently accepting Wesley’s direction in all matters of church governance.

Richard Allen, from the frontispiece of History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (1891)

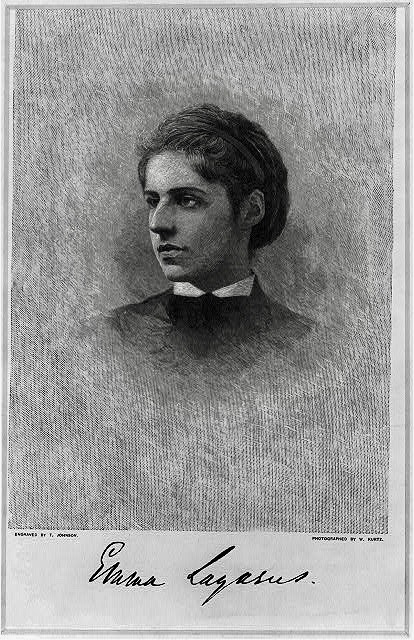

Delegates also voted on rules of behavior for clergymen and lay ministers as well as laity. Ministers were prohibited from consumption of alcohol. All the faithful were enjoined to emancipate any slaves they held (a reform that would prove difficult to enforce in the Southern colonies). Coke also ordained about twelve other lay preachers as elders, notably including an African American delegate, Richard Allen (who would complain of the paternalistic supervision his white colleagues imposed on him and later found the African Methodist Episcopal Church).

Citation

Joe Iovino, “The Christmas Conference: 10 Days That Started a Church” https://www.umc.org/en/content/the-christmas-conference-10-days-that-started-a-church

Russell E. Richey, Kenneth E. Rowe, and Jean Miller Schmidt, American Methodism: A Compact History (Nashille: Abington Press, 2012).

John Wigger, American Saint: Francis Asbury and the Methodists(New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.