The First Parliament of the World’s Religions

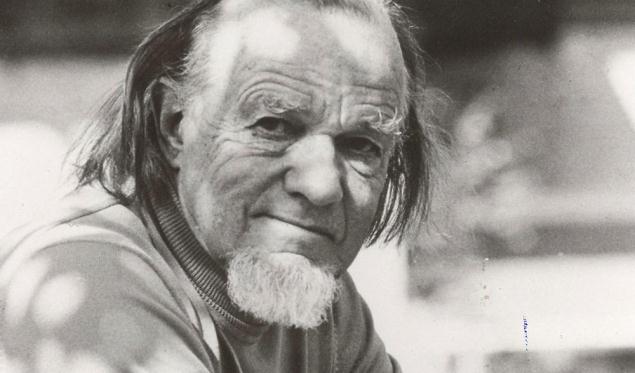

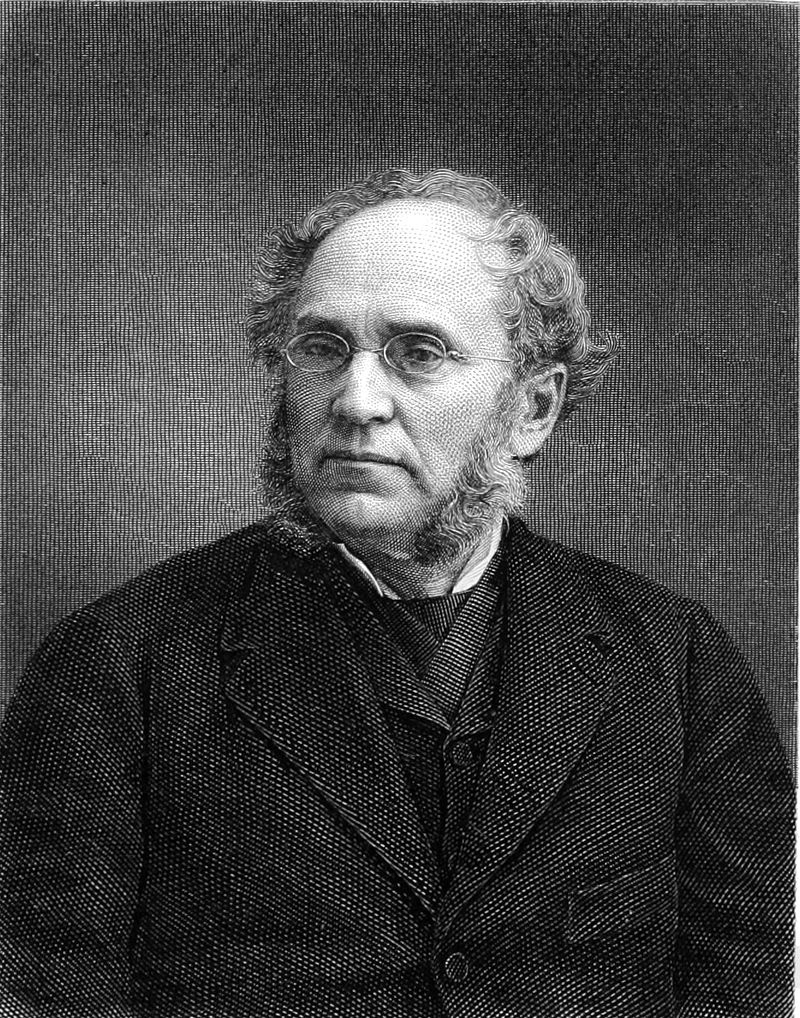

Charles Carroll Bonney. Wikimedia Commons.

The Parliament of the World’s Religions met for the first time from September 11 – 28, 1893 in Chicago, as a project growing out of the World’s Columbian Exposition also held that year. As the Exposition planners arranged demonstrations of the technological advances resulting from four centuries of Euro-American civilization, others argued for demonstrations of the moral and spiritual dimensions of human progress. Led by Charles Carroll Bonney, a layman in the Swedenborgian Church, a committee of Chicago businessmen, clergy, and educators organized a series of international congresses addressing a range of progressive goals, from improvements in medicine and engineering to the promotion of fine arts, the advancement of women, and other social reform projects. Of all these congresses, the World’s Parliament of Religions drew the most public interest.

Hope for a Universal Religious Vision

The Parliament occurred in a moment of what may now seem naïve idealism, when its organizers could profess a hopeful universalism that would draw the adherents of many faiths into a single ethical vision. In a paper written to promote the upcoming Parliament, they said it would aim “to unite all Religion against irreligion; to make the golden rule the basis of this union; and to present to the world the substantial unity of many religions in the good deeds of the religious life.” (Charles Bonney, “Words of Welcome,” 21)

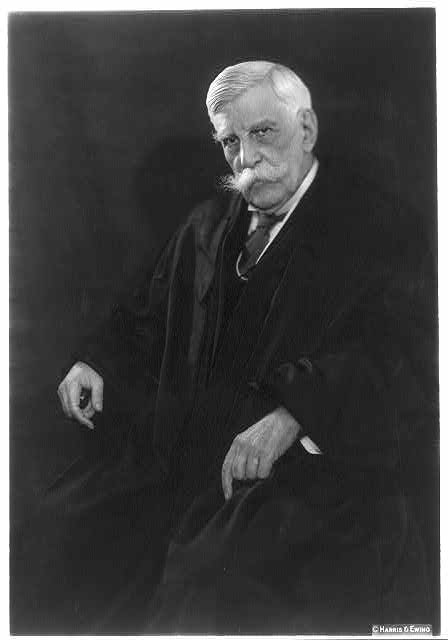

John Henry Barrows (1847-1902), pastor of Chicago’s First Presbyterian Church and Chairman of the Parliament. Wikimedia Commons.

In one sense, the Parliament might be seen as a North American response to scientific developments of the preceding two centuries that challenged Biblical truth as it had been understood: archaeological and philological discoveries shedding light on the composition of the Bible, and geological discoveries and theories of human evolution challenging the Biblical narrative. What needed countering were not challenges to specific doctrines but a tendency to abandon them all while pursuing worldly objects with manmade tools. A universalism that united scientific and religious truth and directed them toward peaceful ends seemed thinkable to many in this period prior to world war and preceding the popularization, by Protestant, Catholic, Jewish and Muslim conservatives, of orthodox doctrines framed to specifically counter modernism.

Charles Bonney, welcoming the delegates to the Parliament, suggested that the scheduled discussions would apply a scientific approach, clearing away misunderstandings that had divided mankind into distinct faiths. These misunderstandings had arisen because human beings failed to note the difference “between appearances and facts” and “between signs and symbols and the things signified and represented.” (General Intro, 18) John Henry Barrows, pastor of Chicago’s First Presbyterian church and the chair of the Parliament, proclaimed that “whoever would advance the cause of his own faith must first discover and gratefully acknowledge the truths contained in other faiths.” (“Words of Welcome,” 26)

Christian Perspectives on Universalism

Boston evangelist Joseph Cook, who, according to a Chicago Tribune report from September 21, 1893, was seen as “the representative of orthodox Protestant Christianity of the stricter type at the parliament.”

Cover design of Volume I of the the Rev. John Henry Barrows’ account of the World’s Parliament of Religions, published in 1893.

However, Christians who addressed the delegates (78% of those who spoke were Christian and the majority of these were American Protestants) often appeared less inclined to a disinterested exploration of other faith traditions than to assimilating those traditions into their own. Some, like Henry Harris Jessup, a Presbyterian missionary to Syria, spoke of Anglo-American Protestantism as carrying the God-given task of enlightening the world to a higher morality demanding that “the strong . . . help the weak” and “the free . . . deliver the enslaved.” (“The Religious Mission of the English-Speaking Nations,” 41). Boston evangelist Joseph Cook went further, arguing that Jesus Christ was the one and only “perfect exemplar of what every man should be” and all human progress depended imitation of him. (Strategic Certainties of Comparative Religion,” 49)

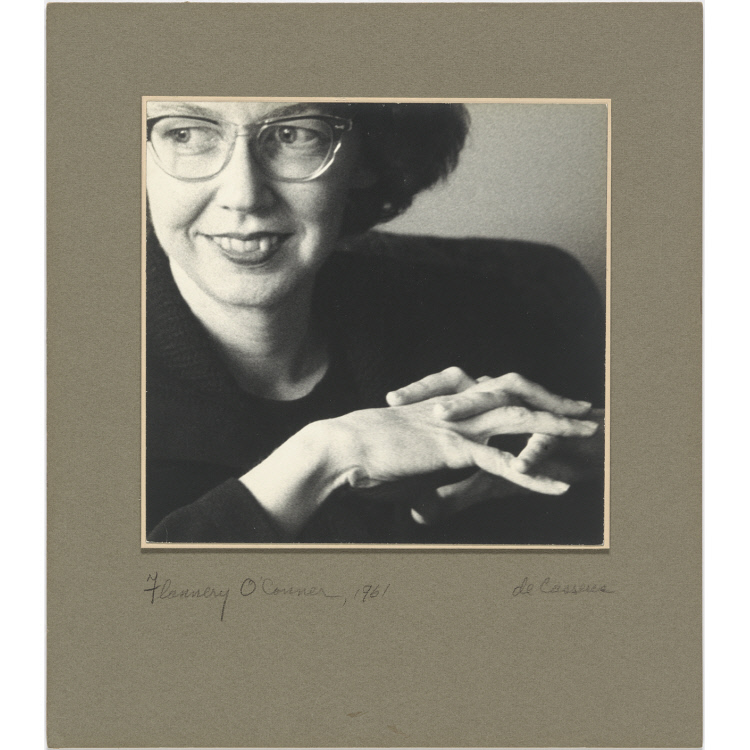

Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb, as pictured on the cover of a biography by Umar F. Abd-Allah.

The American Perspective

Just as most of the Protestant delegates were American, so were most of those in the Catholic, Jewish, and even the Islamic delegations. The Vatican had expressed disapproval of the parliament, but allowed James Cardinal Gibbons and others to speak. Most of those who spoke for Judaism represented the reformist elements of the faith; Kaufman Kohler and Emil Hirsch made notable speeches. Muslims were very underrepresented, perhaps largely because Abdul Hamid II, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, declined to send representatives. The most effective speaker for Islam was Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb, who had become interested in Islam while serving as US Ambassador to the Philippines and eventually converted to the faith. (“The Spirit of Islam,” 270 – 280)

Pung Kwang Yu (Photo from John Henry Barrows, Meeting of the World’s Parliament of Religions Vol. 1, (Chicago: The Parliament Publishing Company, 1893). Courtesy of Newberry Library, Call no. B8.075.

Still, as Eck points out, foreign representation at the Parliament exposed American attendees to points of view they had not heard, including the views of Hindus, Buddhists, and those practicing the Shinto tradition. This was the more significant given that the immigration laws of the time excluded most Asians, (Eck, “Foreword,” xvi) as some of the Asian delegates pointedly noted, while also calling attention to coercive US commercial policies in Asia, such as the “Treaty of Amity and Commerce” negotiated by US Consul Townsend Harris with Japan at a moment when British and French squadrons were threatening to seize commercial rights through force. A subtler diplomatic message was delivered by Pung Kwang Yu, who was First Secretary of the Chinese Legation in Washington, DC and also a Confucian scholar. After drawing comparisons between Christian and Confucian teachings, he thanked the American delegates for their courteous attention and then asked “that they will treat, hereafter, all my countrymen just as they have treated me.”

From Universalism to Pluralism

Richard Seager writes that while a universalist impulse gave rise to the Parliament, the event itself highlighted the multiplicity of human religious thought and experience, leading instead toward a realization of American pluralism. (“General Introduction,” 8) In America, the most important consequences, according to Diana Eck, were growth in the comparative and historical study of religion as an academic discipline and the birth of the both the modern interfaith movement and the modern Christian ecumenical movement. (“Foreword,” xiv – xv)

Exposition grounds, World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, photographed by o Frances Benjamin Johnston. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-104795.

Citation

The Dawn of Religious Pluralism: Voices from the World’s Parliament of Religions, 1893. Edited, with Introductions, by Richard Hughes Seager, with the assistance of Ronald R. Kidd, and with a Foreword by Diana L. Eck. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court Publishing, 1993.