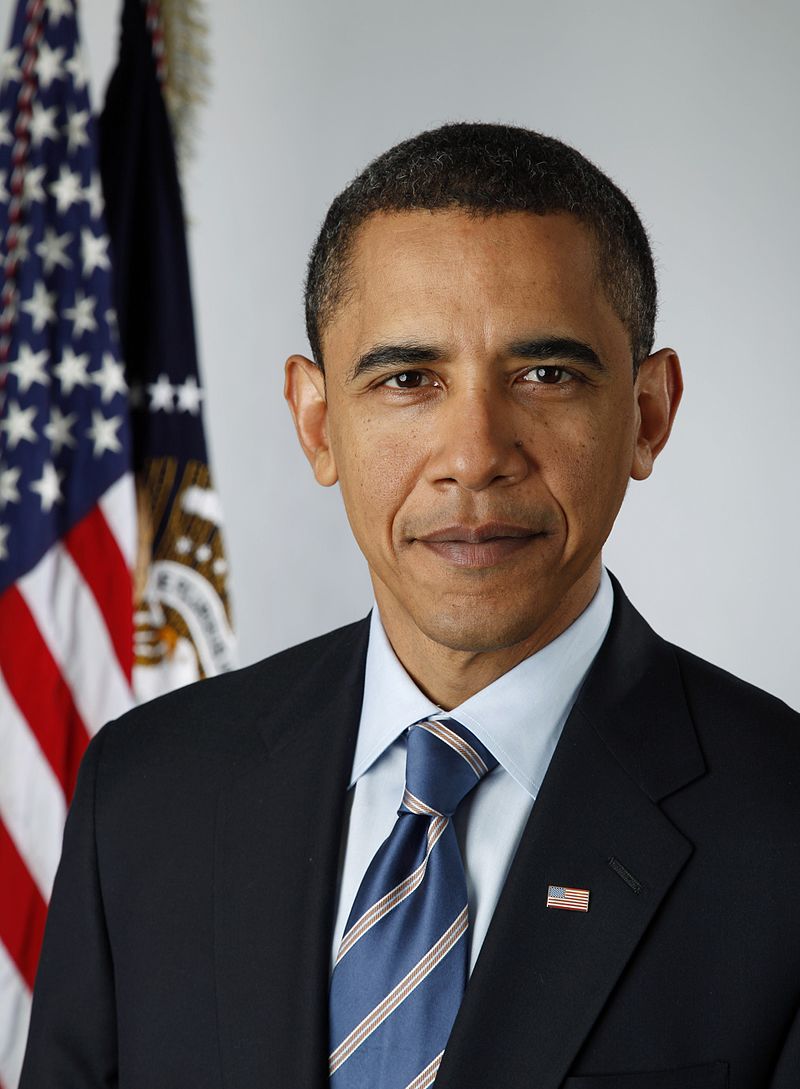

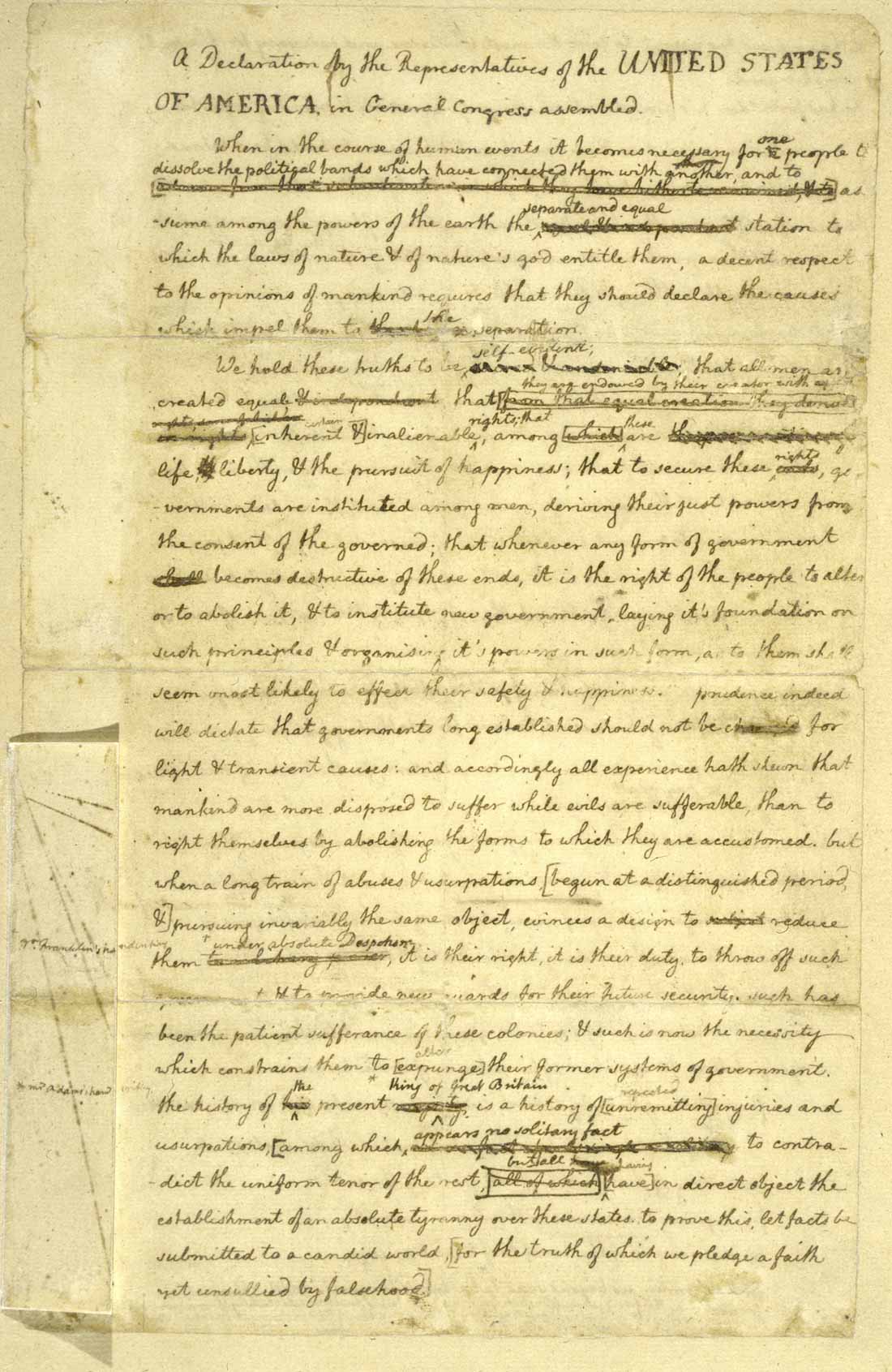

Portrait of Yarrow Mamout: An Early American Muslim

Charles Willson Peale

1819

Yarrow (or Yaro or Yeru) Mamout came to this continent as a slave in 1752. His portrait–and his story–were preserved by artist Charles Willson Peale on the latter’s visit to Georgetown in 1819.

Yarrow (or Yaro or Yeru) Mamout (or Muhammad, Marmoud, or Mamadou) came to this continent as a slave in 1752. He was a Fulani, the nomadic tribe of Muslim Africans that ranged over all of West Africa, predominately in what is now Senegal and Guinea. Yarrow was sixteen years old when he was enslaved, being taken from the Guinea coast to Maryland. We do not and cannot know much about his African life, as Yarrow left no record. However, in 1819, Charles Wilson Peale painted this portrait of him and wrote an obituary for him when he died, telling all he knew about Yarrow and his American life. Subsequently, he is referenced in most books about the Muslim experience in the United States, an anomaly as a slave with portraits.[1]

Allan Austin, in African Muslims in Antebellum America notes that most evidence of Muslims in early America are minor items like their names in slave lists, or birth and death notices that might include a note about the unusual religion (Austin 1997, 5). Knowledge of a sacred text is central to Islam; so Muslim slaves were literate because of the Quran, though perhaps not always literate in English. In some early cases, before use had hardened minds and attitudes towards chattel slavery, a highly literate and clearly Muslim slave might be bought and liberated. Some colonial Americans could not bear to see the devout enslaved, so it was one thing to enslave pagans, but another to enslave a monotheistic believer (Diouf 2013, 72, 138, 191). For slave owners, slave communications, especially in indecipherable Arabic, were extremely suspect for fear of organized revolts. Some individual owners on the East coast might value a literate servant, but most slaves and their owners there kept quiet about such accomplishments (Austin 1997, 33). The exception was New Orleans, where among the French inhabitants literacy could be a prized feature in a slave, along with Muslims’ belief in one god, sobriety, and modest dress and behavior.

Though we know that Yarrow Mamout was at least somewhat literate (certainly in Arabic, but likely also in English, given what we know of his personal accomplishments over a lifetime) he never wrote about himself. We do know he came here on the slave ship Elijah at age 16 in 1752 (Johnston 2012, 7-8). We also know that Samuel Beall bought him and used Yarrow as his body servant until Beall’s death in 1777. This was in Georgetown where Beall was a planter, then an engineer, later the sheriff of Frederick County, and ultimately involved in Revolutionary activities (Johnston 2012, 32). Because of Beall’s prominence, the many people who knew him knew his slave, Yarrow (Johnston 2012, 52). Following Samuel Beall’s death, Yarrow belonged to Brooke Beall, a son who was in the import/export business. In those years, Yarrow worked for pay for other men and despite the presumption of most of his biographers that some of that money went to his owner, he built savings of his own. From the Beall family ledgers, we know he made some small trades in the family business (Johnston 2012, 72). In 1793, he had accumulated enough money to become a shareholder in the Columbia Bank.

Yarrow was nearly sixty years old when Brooke Beall promised the reward of freedom for a life of hard service. He was freed by the family a year after Brooke’s death, in 1796. By law, a slave had to have enough money to live on his own to be freed. Yarrow could prove $100 in cash saved by the time his manumission papers were signed. This was after he had spent £20 to buy his son, named Aquilla, whom he had fathered in 1788 while working for the Chambers family in Montgomery County, Maryland.

Once free, Yarrow made money making and hawking wares around Georgetown with a cart, making charcoal or bricks, weaving baskets, and following the other trades he had learned as a slave when opportunities arose. He worked for prominent gentlemen and was a peculiar local celebrity in his own small way. By 1800, Yarrow Mamout owned a lot in Georgetown at 3324 Dent Place NW. The 1803 Georgetown deed book has a signature in Arabic for a house on the lot valued at $30. (Johnston, 72-74)

In 1818, Charles Willson Peale visited Georgetown, staying with Joseph Brewer, one of Yarrow’s occasional employers. Among the local stories Brewer told him, one was about the old “Mehometan” who owned bank stock and a house on a lot in the town and was reputedly 140 years old. (Johnston 91) At age 77, Peale was interested in longevity and what qualities in life produced the gift of a healthy old age. The next year, in 1819, Peale painted this portrait of Yarrow. Afterwards, he wrote that he believed the old man to actually be 134 years old and said of him,

Yarrow owns a house and lots, and is known by most of the inhabitants of Georgetown, and particularly by the boys, who are often teasing him, which he takes in good humor. It appears to me that the good temper of the man has contributed considerably to longevity. Yarrow has been noted for sobriety and a cheerful conduct. He professes to be a Mahometan, and is often seen and heard in the streets singing praises to God—and, conversing with him, he said man is no good unless his religion comes from the heart.

The truth was that Yarrow was eighty-three years old. However, Peale spent two days in Yarrow Mamout’s house painting his portrait and his report of the conversation with his subject recorded in his diary is a major source of information about the man. In the portrait, the only attribute that tells us that Yarrow Mamout was a Muslim is the cap, styled like a Fulani cap that Yarrow would have worn in his youth.

When Yarrow died in 1823, Peale wrote the obituary and sent it to newspapers. An obituary as news was rare for African Americans, but several papers carried this tribute by Peale. The Gettysburg Compiler was one of those. “He was interred in the corner of his garden, the spot where he usually resorted to pray … Yarrow was never known to eat of swine, nor drink ardent spirits.” This was all the reference to the fact that Yarrow Mamout was a Muslim until he died.

Mamout had deeded the property and house that he had bought and built to his son, Aquilla Yarrow. Aquilla later married Polly Turner, a midwife, and they sold the property, moving to a more rural part of Maryland now called Yarrowsburg, not far from Harper’s Ferry. Like any American family, they alternately prospered and suffered hardship. There is no evidence that the descendants of Aquilla and Polly Yarrow were Muslim. As is true of most Muslims coming to America inevitably as slaves in the early years, they merged with the prevailing Christianity of the American slave experience.

Portrait of Yarrow Mamout (Muhammad Yaro) by Charles Willson Peale, 1819. Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/319114.html. Purchased with the gifts (by exchange) of R. Wistar Harvey, Mrs. T. Charlton Henry, Mr. and Mrs. J. Stogdell Stokes, Elise Robinson Paumgarten from the Sallie Crozer Hilprecht Collection, Lucie Washington Mitcheson in memory of Robert Stockton Johnson Mitcheson for the Robert Stockton Johnson Mitcheson Collection, R. Nelson Buckley, the estate of Rictavia Schiff, and the McNeil Acquisition Fund for American Art and Material Culture, 2011.

Notes

[1] In 2012, James H. Johnston wrote a book about Mamout, which is the fullest account available. It is perhaps necessarily full of surmises and legends, but Johnston also therein records the actual information about Yarrow, the lives of his descendants and the circumstances of life in America for a slave who later became a free black. Return