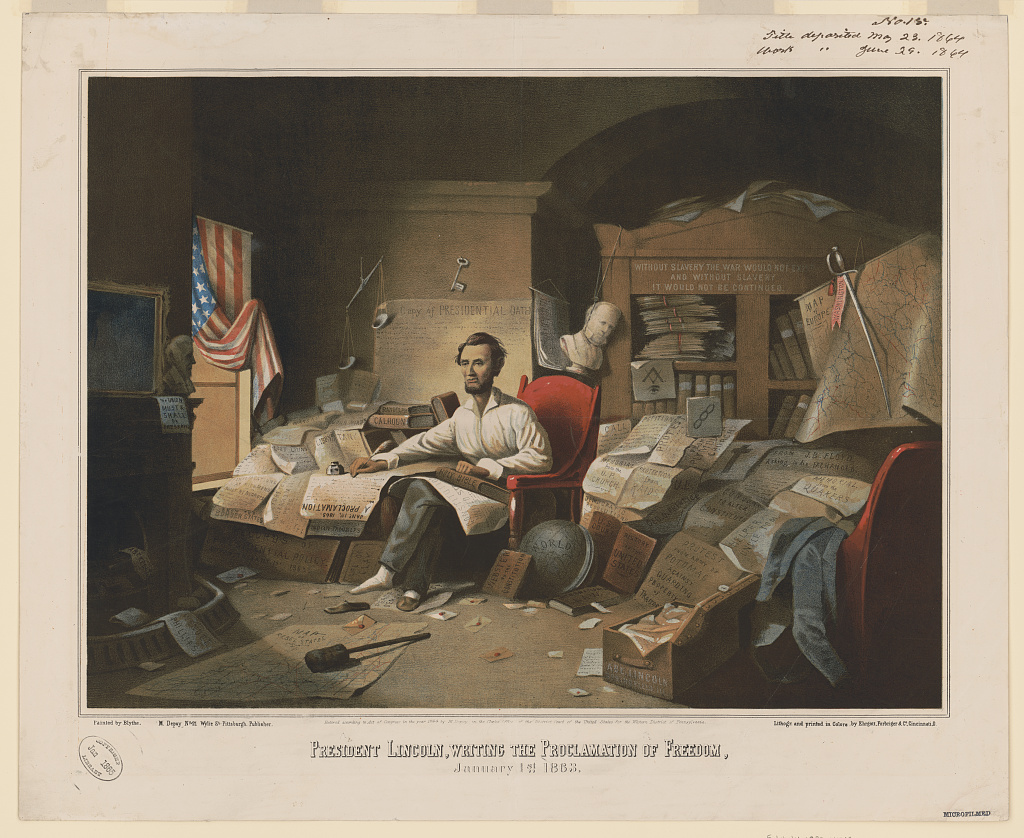

Christianity and the Emancipation Proclamation

David Gilmour Blythe

1863

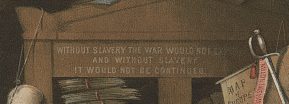

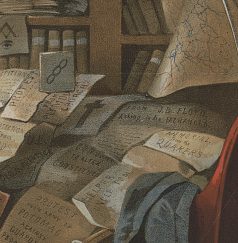

In the artist’s imaginative portrayal of Lincoln’s drafting the Emancipation Proclamation, the president appears in a moment of reflection. He sits in the dawning light of a new day, surrounded by a mess of documents and other decorative items, each of which is meant to symbolize a source of influence on the text.