Francis Pastorius, Germantown, and the First Petition to Abolish Slavery

1688

This year marks the 335th anniversary of the founding of Germantown, an effort led by Francis Daniel Pastorius. Soon after, Pastorius drafted the first North American petition to abolish slavery.

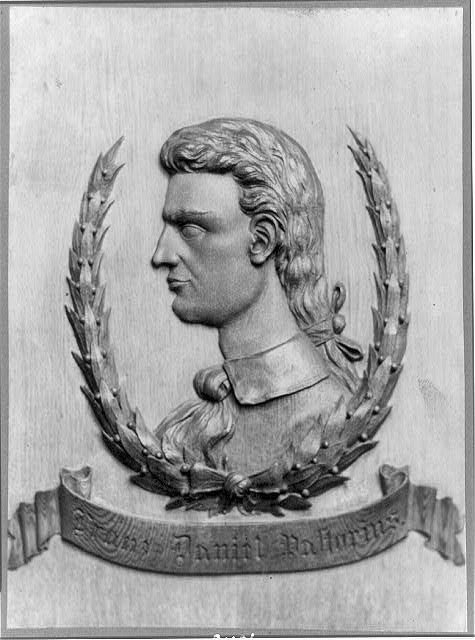

Bas-relief profile of Francis Daniel Pastorius, Founder of Germantown, PA. Photo by Blaul, Germantown Avenue, Philadelphia, ca. 1897.

In October 1683, about eighty German Protestants—Mennonites, Pietists, and Quakers—arrived in Pennsylvania to settle 15,000 acres purchased from William Penn. Francis Daniel Pastorius, a highly educated lawyer from the Duchy of Franconia, led the group. Pastorius had been raised in a prosperous Lutheran family but grew dissatisfied with the church’s cooperation in the oligarchic political arrangements in the German duchies. After joining a Pietist sect of Lutherans in Frankfort, he was recruited to lead the new Pennsylvania settlement. Pastorius traveled ahead of the group, negotiating the purchase of land near the new settlement of Philadelphia, and laying out thirteen family parcels that would be distributed by lot. The new settlement would be called Germantown, and Pastorius would serve for seventeen years as its effective mayor and chief administrator.

Pastorius’ Political and Intellectual Leadership of Germantown

Pastorius designed the town as a linear grouping of homes along a main street, each occupying a narrow but very deep lot. This arrangement meant that neighbors would dwell near each other yet possess enough land to raise food and livestock. Many of those who settled Germantown were skilled weavers, so Pastorius encouraged the development of the linen industry. He also codified the laws of the town, served as rent collector, clerk, court recorder and bailiff, and authored a pamphlet promoting settlement in Pennsylvania.

Sir William Penn, engraved by J. Posselwhite from the print by J. Hall after the picture by West; published by Charles Knight. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-12218.

He was a trusted friend of William Penn and befriended other learned men in the colony. Concerned to gather the knowledge needed by settlers in an untamed wilderness, he bought and borrowed books on a wide range of subjects. He copied and summarized useful information on law, medicine, history, philosophy, gardening, husbandry, and poetics in manuscript commonplace books, creating a 1000-page compilation that he called The Bee Hive.

After stepping down as town administrator in 1700, Pastorius became headmaster of a new Friends school established in Philadelphia, then returned to teach at a similar school established in Germantown. When the new managers of Germantown tried to defraud the original settlers of their property rights, Pastorius used his legal expertise to thwart their effort.[1]

Protest Against Slavery

Pastorius is best known today for leading the first effort by a religious group against slavery in the American colonies, only five years after he founded Germantown. Pastorius drafted a petition, signed by himself and three like-minded citizens of Germantown, urging the local Friends meeting to prohibit slave holding among members.

The opening of the 1688 Germantown Quaker petition against slavery. Photo taken by conservators of the original document (Haverford College Special Collections) and on behalf of the Germantown Monthly Meeting of the Society of Friends. http://www.meetinghouse.info/1688-petition-against-slavery.html.

This monument to Franz Daniel Pastorius was completed by sculptor Albert Jaegers in 1917 but was erected in Vernon Park, Germantown, only in 1920, due to anti-German sentiment during World War I. Beneath the seated figure of “Civilization,” bas relief panels depict notable incidents in Pastorius’s life. The front panel depicts Pastorius as leader of the community with his wife Anneke at his side. The right panel allegorizes the petition against slavery. Photo by Christopher William Purdom, Philadelphia Public Art @philart.net.

Pastorius wrote that slaveholding was “irreconcilable with the precepts of the Christian religion,” as it violated the Biblical teaching to love one’s neighbor as oneself. At the monthly governance meeting in Dublin, Pennsylvania, the petition raised concerns but failed to gain approval (a consensus of opinion, rather than a majority vote, was required for any action taken by Friends meetings). Already, about half of the British Quakers in the Philadelphia and Germantown area owned slaves. These Friends argued that slavery was a practice recognized in the Biblical narrative and critical to the settlers’ prosperity in the new world.

Unable to resolve the question, the local group referred the petition to the Philadelphia Quarterly Meeting. There, the matter was referred to the Yearly Meeting in Burlington, NJ. No action was taken at any level. Given the rule of submission to the will of the community in the Society of Friends, Pastorius and the other signers of the petition had to refrain from further protest while waiting for the “Inner Light” to speak to the whole body of the Friends about the evils of slavery.

Yet an internal discussion of the morality of slavery had begun and would continue.[2] In 1776, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting banned the owning of slaves. Soon after, Pennsylvania Quakers founded The Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and the Relief of Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. In 1785, Benjamin Franklin became head of this group. Shortly before his death in 1790, Franklin would author the petition the group sent to the first Congress, asking it to abolish slavery and act to end the transatlantic slave trade.

The protest Pastorius authored was forgotten, then rediscovered by a Philadelphia antiquarian during the rising abolitionist movement of the 1840s. After emancipation finally came, essayist and poet John Greenleaf Whittier memorialized Pastorius’s antislavery stance in his 1872 poem, “The Pennsylvania Pilgrim.” Whittier, who devoted much of his career to the abolition cause, sees the early Quaker hesitancy to condemn slavery as foreshadowing, in the Biblical authority appealed to by both sides, the debate among slaveholding and non-slaveholding American Christians that continued until passage of the Thirteenth Amendment:

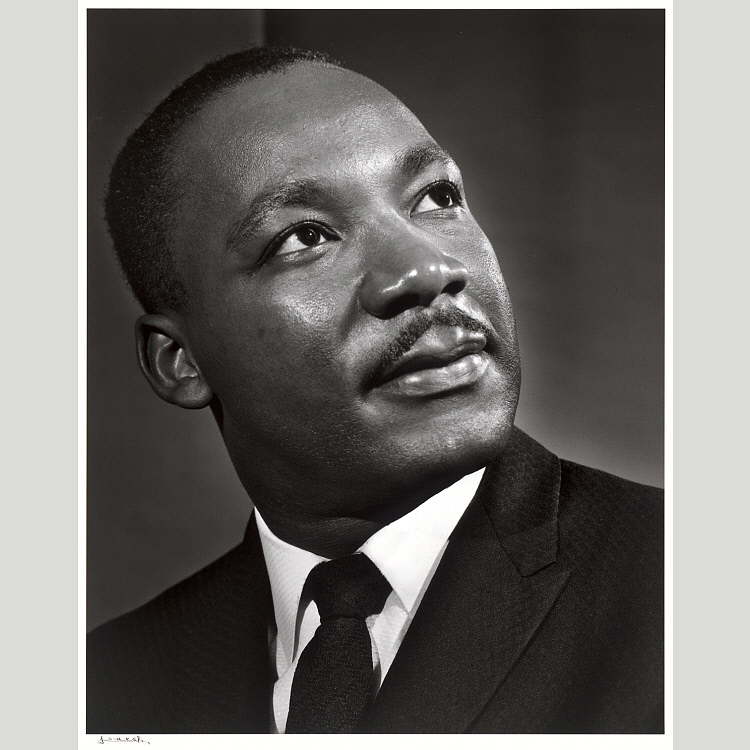

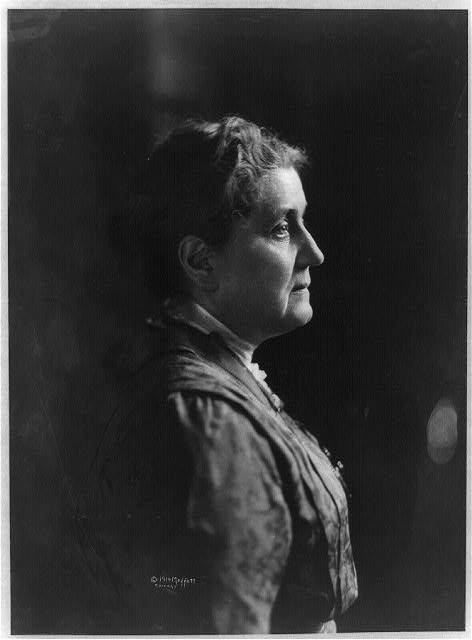

John Greenleaf Whittier, photographed November 25, 1885 (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ6-277).

For all too soon the New World’s scandal shamed

The righteous code by Penn and Sidney framed,[3]

And men withheld the human rights they claimed.

And slowly wealth and station sanction lent,

And hardened avarice, on its gains intent,

Stifled the inward whisper of dissent.

Yet all the while the burden rested sore

On tender hearts. At last Pastorius bore

Their warning message to the Church’s door

In God’s name; and the leaven of the word[4]

wrought ever after in the souls who heard,

And a dead conscience in its grave-clothes stirred

To troubled life, and urged the vain excuse

Of Hebrew custom, patriarchal use,

Good in itself if evil in abuse.

Gravely Pastorius listened, not the less

Discerning through the decent fig-leaf dress

Of the poor plea its shame of selfishness.[5]

Notes

[1] William Gold, “Francis Daniel Pastorius Homestead — Building a Haven for Religious Freedom in Germantown,” PhilaPlace: Sharing Stories from the City of Neighborhoods (Historical Society of Pennsylvania), http://www.philaplace.org/story/1191/Return

[2]Details of the meetings through which the petition passed are based on the story of the petition at the website of the Germantown Mennonite Historic Trust, http://www.meetinghouse.info/1688-petition-against-slavery.html. Susan Sachs Goldman gives a somewhat different account of these meetings in her study, Friends In Deed: The Story of Quaker Social Reform in America (Highmark Press, 2012), p. 87–90. Goldman’s book discusses the larger context of Quaker opposition to slavery during the colonial period, beginning with an open letter George Fox wrote in 1657 “To Friends Beyond the Seas That Have Blacks and Indian Slaves” (see pages 84–105).Return

[3]Algernon Sidney, a Protestant English nobleman and early supporter of republican causes whose principled stands caused him to be accused of treason under Oliver Cromwell and executed by Charles II. He helped William Penn design the colonial constitution of Pennsylvania and wrote a treatise, Discourses Concerning Government, elaborating a theory of natural rights that would influence the thinking of Thomas Jefferson and other American revolutionaries.Return

[4]An allusion to Luke 13:21: “It is like leaven, which a woman took and hid in three measures of meal, till the whole was leavened.”Return

[5]John Greenleaf Whittier, “The Pennsylvania Pilgrim,” Narrative and Legendary Poems, The Poetical Works, Vol. I (Boston, Houghton Mifflin), 1892; online by Bartleby.com, https://www.bartleby.com/372/69.html.Return