The 17th Century Religious Origins of American Independence

Title page from A Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission. Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/12019678.

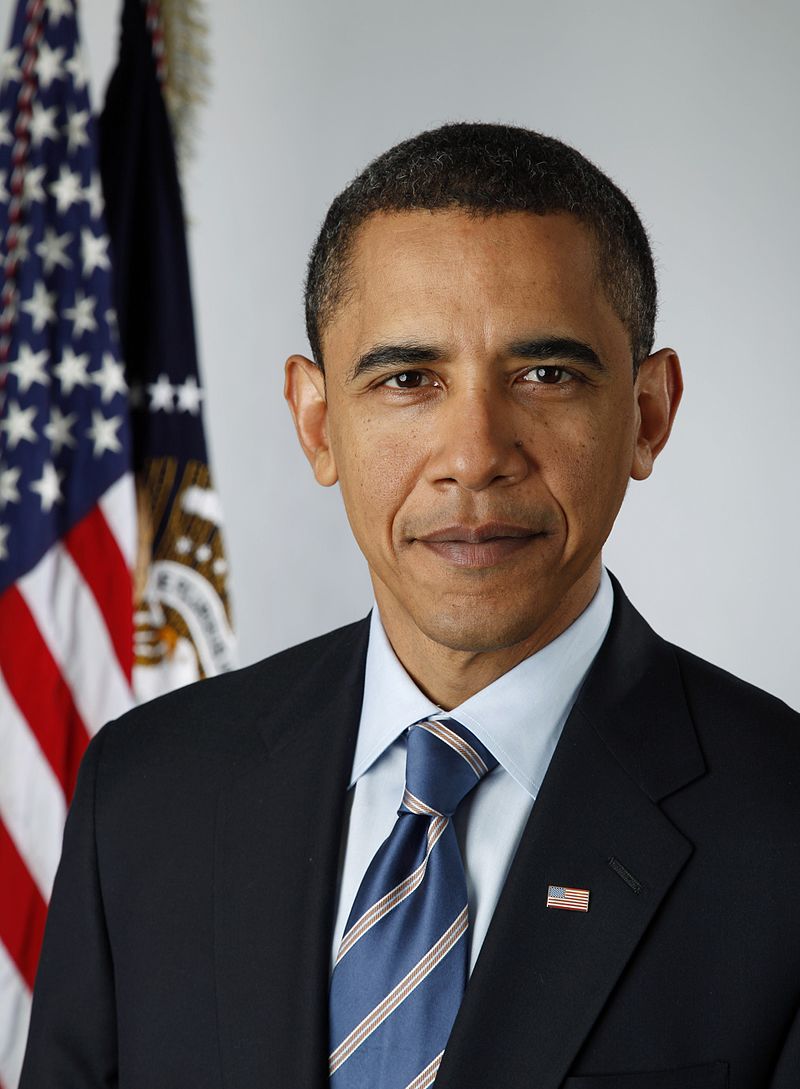

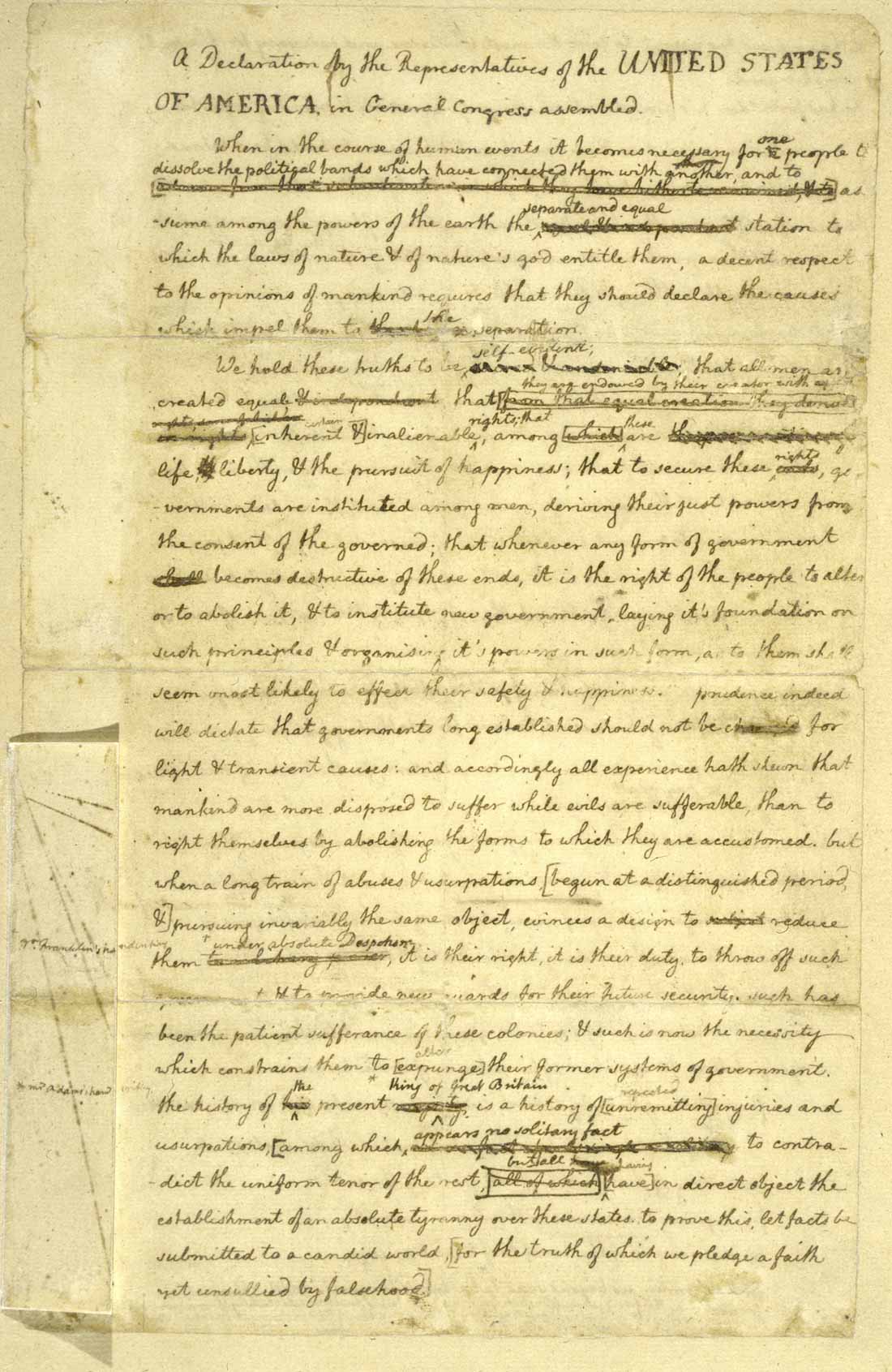

In 1750, Jonathan Mayhew preached a sermon commemorating the anniversary of the execution of Charles I during the English Civil War. Years later, John Adams credited Mayhew’s Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission with helping to “revive” the popular “animosities against tyranny, in church and state” that were central to the revolutionary cause. If we take Adams’ claim not only seriously, but literally, we must understand Mayhew not as offering a radical new interpretation of his text (Romans 13) but, rather, as bringing back to popular attention an old understanding of the same, rooted in the Reformed resistance tradition of the seventeenth century. By looking to Mayhew, we can understand that American Independence was not simply a footnote to Locke; it in fact had a deep basis in Protestant faith.

The Regicide

The English Civil War (1642-1651) joined members of Parliament with those who wanted a more thoroughly reformed Church of England against King Charles I and his supporters who, it was feared, wanted to return England to the Catholic faith. This was a dire threat indeed, for the imposition of religious conformity under a Catholic monarchy would necessitate false faith. Dissenters of all stripes argued that in order for faith to be effectual in the life of an individual (or, by extension, a political community), it could not be coerced. Thus, the threat of religious establishment had not only temporal but eternal consequences.

In light of this, it is perhaps unsurprising that we find otherwise orderly persons willing to advocate the overthrow of the king. In a brief passage in his 1644 book The Key of the Kingdom of Heaven, John Cotton noted that although private individuals ought not to resist duly constituted civil powers on their own, “if some of the same persons be also be trusted by the civil state, with the preservation and protection of the laws and liberties” of the people—that is, if they could reasonably be regarded as holding the position of a lesser magistrate—it was entirely legitimate for such individuals to gather together with others so appointed “in a public civil assembly (whether in council or camp)” to redress injustice. In the context of the English Civil Wars, Cotton’s inclusive parenthetical “in council or camp” is telling: granted that one of the major grievances against King Charles I was his refusal to regularly call Parliaments, it seems likely Cotton envisioned some sort of extra-Parliamentary body of nevertheless recognizable civil officers might be led to action on the people’s behalf. Arguably, this is indeed what happened a few years later, in 1648, when the New Model Army forced the Long Parliament to disperse.[1] Cromwell’s execution of Charles I in 1649 as a traitor to the people of England, then, makes a certain amount of sense, as does the choice of New Englanders to hide the regicides Edward Whalley and William Goffe from royal retribution after the Restoration of Charles’ son, Charles II in 1660.

The Restoration

As Mayhew would write in 1765,

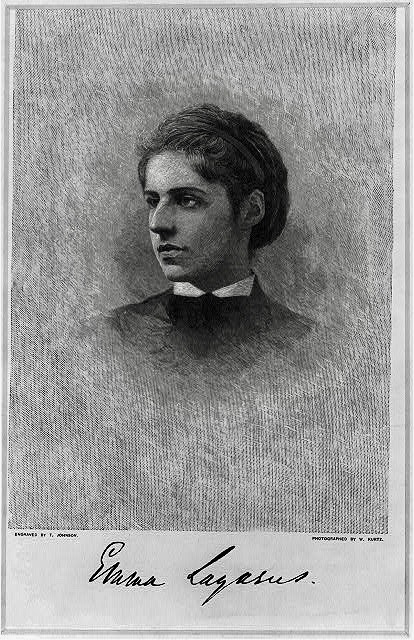

Town Meeting. Engraving by Elkanah Tisdale. Illustration from John Trumbull, M’Fingal : a modern epic poem, in four cantos (New-York : 1795). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-7714.

The colonies are universally and greatly alarmed at the Measures lately taken respecting them. . . . What may, in time, be the consequence of raising a general and great dissatisfaction in the people of this large Continent, no one can certainly foresee. But you and I, Sir, are at least clear in this point, that no people are under a religious obligation to be slaves, if they are able to set themselves at liberty. (Letter to Thomas Hollis, 8 August 1765)

If these were radical sentiments, they were not novel ones, for Mayhew was simply following in the footsteps of a long tradition of religiously inspired resistance to royal absolutism. Over the course of the next several years, churches around the colonies would serve as the natural gathering places for the people to discuss their reaction to the unjust and oppressive actions taken by the British government, as seen in this engraving. Indeed, the line between secular and religious resistance was quite permeable, especially after Parliament passed the Declaratory Act in 1766 which asserted their right to legislate over the colonists “in all cases whatsoever.” This was not only tyrannical, but heretical; not only an abridgment of their people’s natural and traditional right to representation, but also a usurpation of the absolute authority those in the Reformed tradition argued belonged only to God. Under such circumstances, for Mayhew and others, resistance even to the point of revolution was thus not only a prudential civic act but a sacred religious duty.

Notes

[1]John Cotton on the Churches of New England, Larzer Ziff, ed. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968), 156; Francis J. Bremer, “In Defense of Regicide: John Cotton on the Execution of Charles I,” The William and Mary Quarterly 37, no. 1 (1980): 106-107.Return