The Seixas Family and Civic Life in the New American Republic

The Seixas family welcomed the American Revolution, confident it would safeguard their freedom to worship in their Jewish faith and engage in business. Their active engagement in the new nation’s civic life came from this conviction.

A signed copy of the Alhambra Decree, or Edict of Expulsion, issued on March 31, 1492, by Isabella I of Castille and Ferdinand II of Aragon, ordering all practicing Jews to leave Spain by the end of the following July (Wikimedia Commons).

The experience of religious persecution was a recent memory in the family of Moses Seixas, lay leader of the Touro synagogue when George Washington visited it in 1791. A determination to counter religious discrimination seems to have motivated the Seixas family’s engagement in the civic life of the emerging American republic. Moses was the oldest son of Isaac Mendes Seixas, who himself was said to be the son of a Portuguese “converso”—that is, a professed convert to Christianity. Conversion was the only option for Jews who wished to remain on the Iberian Peninsula when, in 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella abruptly expelled the entire Jewish population of Spain, and when in 1496 the expulsion was reenacted in Portugal. Yet many conversos were suspected of secretly continuing to adhere to their traditional faith. The Seixas family was accused of this in 1725. They fled to London, there resuming synagogue worship. Isaac made his way to Barbados, but found life for Jews restricted there.

Isaac Seixas Settles in British North America

In the 1730s, Isaac Seixas immigrated to New York, where he became a successful merchant, married, and started a family. In 1765 he relocated the family to Newport, where a small group of Jewish immigrants from Barbados had settled a century prior. Here Isaac’s eldest son Moses set down roots, becoming lay leader of the Touro synagogue, representing it when Newport welcomed President George Washington’s 1790 visit, and writing the letter that prompted Washington’s famous response. Moses Seixas helped found the Newport Bank of Rhode Island in 1795, serving as its cashier the rest of his life.

The family maintained ties to New York, however, also establishing connections in Philadelphia; Isaac’s fourth son Benjamin was a merchant in all three cities and was a founder of the New York Stock Exchange. Another son, Abraham, served as an officer in the Revolutionary Army and would settle after the war in Pennsylvania.

The First American-born Synagogue leader

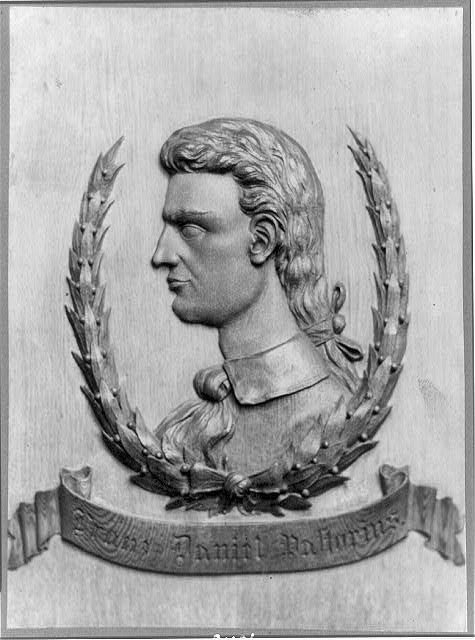

Gershom Mendes Seixas, by James Francis Brown, after an unidentified artist, ca. 1920 – 1930 (Columbia University, Art Properties, Access. no. COO.84 CU, library.columbia.edu/locations/avery/art-properties.html,

Of all Isaac’s sons, Gershom Mendes Seixas, considered the first American-born leader of a Jewish synagogue, played the most prominent role in civic life. In 1668, the young man of 23 was called to lead the synagogue community in New York City, Shearith Israel. He lacked formal rabbinical training; but no ordained rabbi would lead an American synagogue before the mid-nineteenth century. He probably learned Hebrew and studied Talmud (the accumulated commentaries on the Torah that form the basis of Jewish law) under his father Isaac or under a previous synagogue leader, an immigrant from Amsterdam. Like this predecessor, Gershom Seixas served as “hazzan” of Shearith Israel, assuming many roles beyond the traditional cantor’s duties of leading prayer and reading scripture during services. He performed marriages and funerals, became a highly skilled ritual circumciser, interpreted Jewish law for his congregation, and supervised their dietary practices.

Well-read although self-taught, Gershom Seixas formed friendships with leading Protestant citizens and clergy. As the movement for American independence began, he made his support known. When the British occupied the New York harbor in August of 1776, he convinced most of his congregation to relocate to Connecticut, where they would be less vulnerable to British reprisals against patriots. In 1780 he was called to lead the newly established synagogue of Mickve Israel in Philadelphia, again leading his congregation to resettle. At the conclusion of the war, he was called back to New York to once again lead Shearith Israel.

Gershom Mendes Seixas’ Support of the American Revolution and Founding

In his sermons, Seixas spoke of the justice of the Revolutionary cause; as a citizen, he advocated for religious liberty, petitioning the Pennsylvania legislature to reconsider a religious test for office they imposed in 1783.

The title page of the printed version of the thanksgiving sermon Seixas delivered on November 26th, 1789

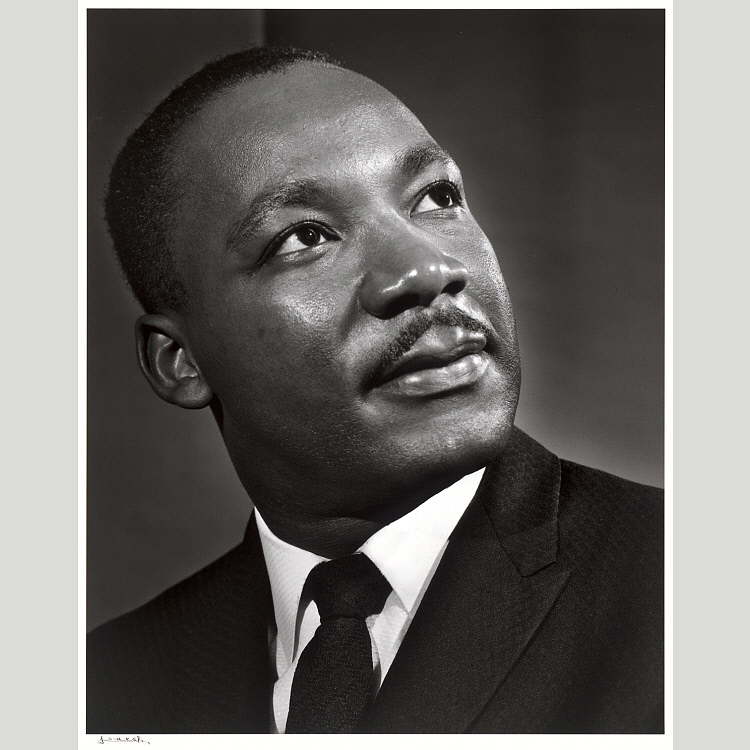

Following adoption of the US Constitution, Seixas was one of a select group of clergymen asked to participate in the inaugural ceremonies for the first president, George Washington. When Washington named November 26, 1789 as a day of public thanksgiving and prayer for the new nation, Seixas delivered a Thanksgiving address to his congregation, in which he exhorted his congregation to

. . . behave in such a manner as to give strength and stability to the laws entered into by our representatives; to consider the burden imposed on those who are appointed to act in the Executive Department; and to contribute, as much as lays within our power, to the support of that government which is founded upon the strict principles of equal liberty and justice. . . .

If, to seek the peace and prosperity of the city wherein we dwell, be a duty even under bad governments, what must it be when we are situated under the best of Constitutions? It behooves us to unite, with cheerfulness and uprightness, upon all occasions that may occur in the political as well as the moral world, to promote that which has a tendency to the public good. As Jews, we are even more than others, called upon to return thanks to God for placing us in such a country – where we are free to act according to the dictates of conscience, and where no exception is taken from following the principles of our religion.

Seixas’ sermon was recognized outside of his own congregation, being published in pamphlet form and commented upon in the New York Daily Gazette.

Forging a Public Role for Jewish Clergy

Howard Berman writes that Seixas modeled a public and “ambassadorial” role for Jewish clergy in a new kind of society, one that allowed for religious pluralism. In a departure from Jewish custom, he invited clergy of other faiths to hear his sermons. He also adopted a style that the dominant society would find familiar, dressing in the black clerical robe and white tab collar that Protestant clergy wore and allowing himself to be addressed as “Reverend.” In developing a close personal relationship with members of his congregation, Seixas may have been influenced by his Protestant colleagues.

One of the most important acquisitions for a newly settled Jewish community is a place of burial. Shearith Israel has built several cemetaries since its founding. The Third Cemetery of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue Shearith Israel in the City of New York served the congregation from 1829-1851. It is located on West 21st Street, west of the Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Avenue), in the Flatiron District, Manhattan, New York City (Photo by Beyond My Ken, 2010, Wikimedia Commons).

In return, he may have helped Protestant colleagues challenge cultural attitudes toward charity. Seixas founded Jewish charitable organizations that provided free burials and other tactfully discreet assistance to the poor. He taught that wealth was not a sign of God’s favor, but a gift God meant for the fortunate person to share with the less fortunate. Michael Feldman notes that in this Seixas contradicted “the reigning Protestant doctrine of his time” (Feldman presumably refers to Puritan ideas about outward manifestations of grace); but Yitzok Levine, pointing out the frequency of Seixas’ sermons on this topic, suggests that the small Jewish minority also needed to hear their view of wealth challenged.

In tribute to his role in the New York community, Seixas was asked in 1784 to serve as one of the original trustees of Columbia College (later Columbia University), a school originally affiliated with the Church of England. He remained a trustee until shortly before his death in 1816.

Citation

Howard A. Berman, “The First American Jew: A Tribute to Gershom Mendes Seixas, ‘Patriot Rabbi of the Revolution,’” Issues of The American Council for Judaism (Spring 2007), http://www.acjna.org/acjna/articles_detail.aspx?id=442.

Michael Feldberg, editor, “Gershom Mendes Seixas: The First American-born ‘Rabbi,’” Blessings of Liberty: Chapters in American Jewish History (The American Jewish Historical Society, 2002), p. 24–25.

Yitzchok Levine, “Gershom Mendes Seixas, American Patriot”: a three-part column, The Jewish Press, May 1, 2014; June 3, 2014; and July 1, 2014.