The Negro’s and Indian’s Advocate, Suing for Their Admission Into the Church

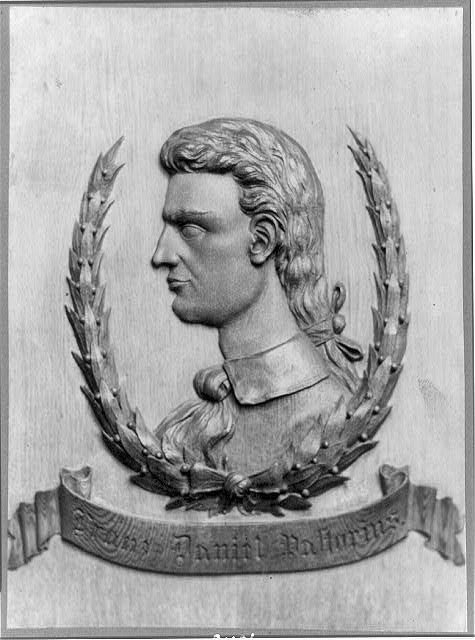

Morgan Godwyn

1680

In this appeal on behalf of those enslaved in the West Indies, Anglican minister Morgan Godwyn argues that slaves should be offered Christian instruction and baptism.

Editor’s Introduction

While living and working in Barbados, Morgan Godwyn, an Anglican minister, wrote a long petition on behalf of the people enslaved in the British West Indies. He addressed it to the Archbishop of Canterbury, yet he also arranged for its publication. He expected his work to be denounced by English planters in America. According to his own account, he had already argued with them about their unwillingness to offer spiritual education and baptism to their slaves.

In his introduction (excerpted below) Godwyn quotes a pamphlet written by a Quaker that accuses Anglican priests of abandoning their calling by neglecting the spiritual care of enslaved people. Godwyn is careful to preface the long quotation with scornful remarks about the Quaker’s intent to undermine his commitment the Anglican church. Yet he pointedly uses the Quaker’s accusations to introduce his own argument. He thereby gives evidence that objections to the treatment of enslaved people were already current among some members of the Society of Friends.

A chief objection to baptizing slaves was the opinion, expressed periodically in the English common law, that fellow Christians could not be enslaved. For example, a 1677 ruling (Butts v. Penny) concerning whether slaves fell under the requirements of the Navigation Act stated that Africans, because they were not only “usually bought and sold among merchants, as merchandise,” but also because they were “infidels,” could legally be considered property. Godwyn does not discuss the legal issues bearing on the baptism of slaves (and indeed, within a few decades common law rulings would stipulate that baptism had no bearing on the status of the enslaved). Instead, Godwyn addresses the theological and ethical issues.

The excerpt below from Chapter 1 of Godwyn’s treatise attacks the common view among slaveholders that Africans were subhuman and therefore incapable of receiving religious instruction. Godwyn argues the absurdity of this position, rejecting claims that Africans in any way fell short of the physical, mental, and moral capacities of those who held them in bondage. Godwyn reduces the slaveholders’ position to the claim that the simple status of being enslaved robbed a person of his soul. This, he shows, is both absurd and blasphemous, since it imputes to slaveholders a power of God alone.

SOURCE: Morgan Godwyn, The Negro’s & Indians Advocate, Suing for their Admission into the Church: or, A Persuasive to the Instructing and Baptising of the Negroes and Indians in our Plantations (London, 1680; Kessinger Legacy Reprints, 2010), p. 1 – 7, 12 – 14, and 28 – 30. This transcription has modernized spelling and capitalization, while retaining Godwyn’s frequent use of italics to add emphasis.

*****

The Introduction

Wherein the temper and inclination of our people here (viz. in Barbados) as to the promoting of Christianity among their slaves, or other heathen, is described; and the motives for writing this discourse are shown, with the necessity thereof.

1. It having been my lot since my arrival upon this island, to fall sometimes into discourses touching the necessity of instructing our negroes and other heathen in the Christian faith, and of baptizing them (both which I observed were generally neglected), I seldom or never missed of opposition from some one of these three sorts of people: The first, such, as by reason of the difficulty and trouble, affirmed it not only impracticable, but also impossible. The second, such as who looked upon all designs of that nature, as . . . not in the least expedient or necessary. The third, such (and these I found the most numerous) who absolutely condemned both the permission and practice thereof, as destructive to their interest, tending no less mischief than the overthrow of their estates, and the ruin of their lives, threatening even the utter subversion of the island. Who therefore have always been very watchful to secure that door, and wisely to prevent all such mischievous enterprises. Themselves in the meantime employing their utmost skill and activity to render the design ridiculous; thereby to affright the better disposed (if any) from ever consenting to an act, which . . . would so much call their discretion and wisdom into question.

2. This spirit of gentilism (for that is the mildest name it will deserve)[1] was principally occasioned through the want of care in the seating of these colonies, where religion ought to have been planted together with the first inhabitants, as amongst all Christians, besides ourselves, hath elsewhere been generally practiced: But the English, for being of the best religion, are to be excused. ’Tis true, the Negro’s ignorance of our language was for some time a real impediment thereto, . . . but none afterward, when they had arrived to an understanding, and discoursing in English, equal with most of our own people; which many thousands of them long since have . . . .

3. Now to represent this more plausible to the world, another no less disingenuous and unmanly position hath been formed . . . that the Negroes, though in their figure they carry some resemblances of manhood, yet are indeed no men. A conceit like unto which I have read, was some time since invented by the Spaniards, to justify their murdering the Americans. [This claim] , if atheism and irreligion were the true parents who gave it life, surely sloth and avarice have been no unhandy instruments and assistants to midwife it into the world, and to foster and nurse it up. Under whose protection getting abroad, it hath acquired sufficient strength and reputation to support itself; being now able not only to maintain its ground, but to bid defiance to all its opposers, who in truth are found to be but very few. . . . The issue whereof is, that as in the Negroes all pretense to religion is cut off, so their owners are hereby set at liberty, and freed from those importunate scruples, which conscience and better advice might at any time happen to inject into their unsteady minds. . . .

4. Now whilst in my thoughts I reflected upon these . . . absurd positions . . . . which I had often heard . . . no less impudently urged and asserted, than I saw universally practiced, a petty reformado pamphlet[2] was put into my hand by an officious FRIEND, or Quaker of this island, (I suppose, in order to my conversion); upon the perusal whereof . . . I met with this malicious (but crafty) invective, leveled against the ministers, to whom it was by the way of interrogatory, directed and applied in no other than these words:

Who made you ministers of the gospel to white people only, and not to the tawny and black also? . . . Why do you not teach your people in this part of their duty, or at least show them the way by your example, beginning at home with those of your own families, whom you cannot deny but you neglect as much as you do the rest? . . . Doth not this silence proceed from a fear of men, whom you are loath to displease . . . for what covetous ends your selves best know? And do you not thereby testify that you are men-pleasers and hirelings, but not the servants of God, nor as you falsely pretend, ministers of Jesus Christ, who, as in your catechism (if you ever read it) doth confess, came to redeem all mankind, without excepting NEGROES and INDIANS?. . . His ministers and apostles were by him commanded to preach the gospel to all the world, and to be witnesses to him to the uttermost parts of the Earth. Is this the way to set forward the salvation of all men, and to make the ways of God and of the gospel known unto all nations, and to all conditions of men therein, not omitting slaves, nor any other? Is this to prepare the way of Jesus Christ against his second coming to judge the world, by turning the hearts of the disobedient to the wisdom of the just, and to approve your selves faithful and true pastors, earnestly feeding the flock of Christ, and preaching his word unto them, as in your collects (as you call them) you pretend to pray? Is this to follow the saints in all godly and virtuous living, who as you read, Mark the 16th and the last verse, went forth preaching everywhere, and ventured their lives into all the world to preach the gospel to the heathen, when you neglect it in your parishes and families?. . . Is this to be diligent to frame and fashion your own lives and your families according to the doctrine of Christ, and to make both your selves and them . . . wholesome examples and patterns to the flock of Christ, laying aside all study of the world and the flesh? . . .

- Now upon this I began to question with myself, if the gospel be good tidings, why should it be concealed, or hid? And since designed so to all people, why should not these partake of it as well as others? If we are bound to pray for their conversion, why are we not also to endeavor it? And since that our blessed Lord commanded his apostles, St. Matt. 28, to go and make disciples of ALL the heathen, why may it not be alike lawful for me, with the great Apostle (Heb. 2:8), to both argue and conclude, in that he said all, he had excepted none? I then also fell to reflect upon the doom of the unprofitable servant; and that since Christ had been thus merciful to me, putting me into the ministry, so unworthy of it, I could have no pretense to be silent . . . lest thereby I should justly incur the like doom. And withal, observing that no abler advocate for them had appeared, I concluded myself under some obligation . . . . to admonish our people of this neglect, and if possible to convince them of the wickedness of those horrid positions and principles . . . as also of the necessity of their speedy applying themselves to that great duty hitherto so unchristianly omitted. Whereupon my thoughts after some time, resolved themselves into these three general assertions.

1. That the Negroes (both slaves and others) have naturally an equal right with other men to the exercise and privileges of religion, of which ’tis most unjust in any part to deprive them.

2. That the profession of Christianity absolutely obliging to the promoting of it, no difficulties nor inconveniences, how great soever, can excuse the neglect, much less the hindering or opposing of it, which is in effect no better than a renunciation of that profession.

3. That the inconveniences here pretended for this neglect, being examined, will be found nothing such, but rather the contrary.

Chapter 1.

. . . . .

II. 1. . . . It being granted for possible that such wild opinions [as that the Africans are not fully human], by the inducement and instigation of our planters’ chief deity, profit, may have lodged themselves in the brains of some of us, I shall not fear to betake myself to the refuting of this . . . . For the effecting of which, me thinks, the consideration of the shape and figure of our Negroes’ bodies, their limbs and members; their voice and countenance, in all things according with other men’s; together with their risibility[3] and discourse (man’s peculiar faculties) should be a sufficient conviction. How should they otherwise be capable of trades, and other no less manly employments: as also of reading and writing; or show so much discretion in management of business, eminent in diverse of them; but wherein (we know) that many of our own people are deficient, were they not truly men? These being the most clear emanations and results of reason, and therefore the most genuine and perfect characters of homoneity . . . . Or why should their owners, men of reason no doubt, conceive them fit to exercise the place of governors and overseers to their fellow slaves, which is frequently done, if they were but mere brutes? Since nothing beneath the capacity of a man might rationally be presumed proper for those duties and functions, wherein so much of understanding, and a more than ordinary apprehension is required. It would certainly be a pretty kind of comical frenzy, to employ cattle about business, and to constitute them lieutenants, overseers, and governors, like as Domitian [4] is said to have made his horse a Consul. . . .

21. . . . It being not to be imagined by sober men . . . that misfortunes and evil accidents should carry that force in them as to alter substances . . . [or] . . . take away the nature of things. For he that before was a rich man or potentate, is still a man . . . . Marius was as much a man when concealed in the marsh and dungeon, as when he arrived to be Consul the seventh time.[5] And Caesar when in the pirates’ hands, was the same man, as when he got to be perpetual dictator. David was but a man when he was King of Israel; and so he was too, when pursued by Saul. Nor did Job become a beast upon his great losses, any more than he could be supposed more than a man, upon his restoration. Now slavery is but a lower degree of poverty and misery; but not the lowest, for there are conditions more calamitous; as to be deprived of all the comforts of life by a perpetual confinement and necessity, with a continual dread and expectation of a miserable death. So also to be vexed with loathsome ulcers, and sharp tormenting diseases, all hopes of relief and respite being cut off; are conditions to which slavery, simply and alone, is to be preferred. Yet none of these do unman the party, though they may much humble and debase him. Such evils altering only the outward state of things, but making no impression upon the inner man, further than as ourselves shall give way thereto . . . . An adverse fortune may deprive us of our goods and liberty, but not of our souls and reason. Of which whilst we are possessed, and do quietly enjoy, ’tis neither the ambition nor covetousness, much less the frowns and menaces of any imperious or tyrannical lord, can bereave us of that right which we naturally have to be ranked within the degree and species of man.

22. And to manifest this, I will suppose, what I would be loath should happen, that some one of this island going for England, should chance to be snapped by an Algerian, or corsair of Barbary, and there to be set on shore and sold,

[6] doth he thereupon become a brute? If not, why should an African . . . suffer a greater alteration than one of us? . . .

23. If slavery had that force of power so as to unsoul men, it must needs follow, that every great conqueror might at his pleasure, make and unmake souls, and a servant running away, or buying his freedom, would make himself one. . . . And the having, or not having of a soul, would signify but the bare enjoyment or want of liberty, of which a horse is no less capable than a man.

24. But that conquest and subjection can make no impression upon the soul, is plain even from this, that it cannot effect a less thing: not subdue the will, which yet is under the command of the soul, but not within the adversary’s power: a victory being rarely heard of which makes the affections to yield, and reduceth the will of the conquered party . . . .

25. And here withal it might be considered, how monstrous and inhumanly cruel they are, who do both buy and retain in this soul-murdering and brutifying state of bondage, those whom they might so easily restore to the pristine homoneity, and of mere beasts, with one little blast of their mouths, even but a word or two, convert into men, and be at the same time the happy authors of life to souls, as well as freedom to bodies. A privilege too great and glorious for the rest of the world to enjoy, and yet not regarded here. . . .

Notes

[1]heathenismReturn

[2]a tract written by a member of a dissident sect aiming at reforming Christian practicesReturn

[3]sense of humorReturn

[4]Roman emperor between AD 81 and 96 known for his cruelty and ostentation. He ruled after the Roman republic ended and the elective office of consul became a nominal, powerless title.Return

[5]The Roman general Marius (c. 157 – 86 BCE) served an unprecedented seven times as consul (one of two chief magistrates in the ancient Roman republic), the last time after returning from an exile during which, according to Plutarch, he narrowly escaped being captured and murdered on numerous occasions.Return

[6]The Barbary Corsairs were pirates operating out of ports on the coast of North Africa during the 17th and 18th centuries. Raiding coastal towns in Europe and attacking shipping, they took European captives whom they either ransomed or sold to the Arab slave market.Return