Why am I a Heathen?

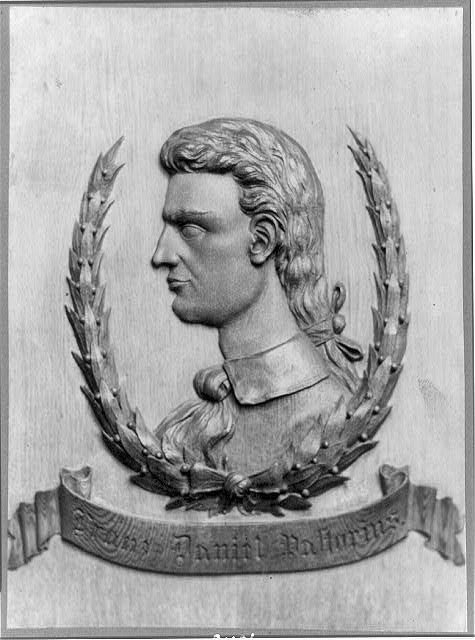

Wong Chin Foo

August 1887

Wong Chin Foo (1847-1898) became a naturalized American in 1874. Shortly thereafter, he proclaimed himself to be the first missionary of traditional Chinese religions (Confucianism and Buddhism) in America.

Why Am I a Heathen?

Men raised in a certain faith usually adhere to it, or drift into one of its cognates. Thus a heathen may wander from simple Confucianism into some form of Buddhism or Brahminism, just as a Christian may tire of following the Golden Rule, and adopt some special sect—one more latitudinarian or ceremonious, according to the temper of his religious conscientiousness; but the latter continues still a Christian, though a pervert; while the heathen in Christian parlance, is still a pagan.

The main element of all religion is the moral code controlling and regulating the relations and acts of individuals towards “God, neighbor, and self;” and this intelligent “heathenism” was taught thousands of years before Christianity existed or Jewry borrowed it. Heathenism has not lost or lessened it since.

Born and raised a heathen, I learned and practiced its moral and religious code; and acting thereunder I was useful to myself and many others. My conscience was clear, and my hopes as to future life were undimmed by distracting doubt. But, when about seventeen, I was transferred to the midst of our showy Christian civilization, and at this impressible period of life Christianity presented itself to me at first under its most alluring aspects; kind Christian friends became particularly solicitous for my material and religious welfare, and I was only too willing to know the truth.

I had to take a good deal for granted as to the inspiration of the Bible—as is necessary to do—to Christianize a non-Christian mind; and I even advanced so far under the spell of my would-be soul-savers that I seriously contemplated becoming the bearer of heavenly tidings to my “benighted” heathen people.

But before qualifying for this high mission, the Christian doctrine I would teach had to be learned, and here on the threshold I was bewildered by the multiplicity of Christian sects, each one claiming a monopoly of the only and narrow road to heaven.

I looked into Presbyterianism only to retreat shudderingly from a belief in a merciless God who had long foreordained most of the helpless human race to an eternal hell. To preach such a doctrine to intelligent heathen would only raise in their minds doubts of my sanity, if they did not believe I was lying.

Then I dipped into Baptist doctrines, but found so many sects therein, of different “shells,” warring over the merits of cold-water initiation and the method and time of using it, that I became disgusted with such trivialities; and the question of closed communion or not, only impressed me that some were very stingy and exclusive with their bit of bread and wine, and others a little less so.

Methodism struck me as a thunder-and-lightning religion—all profession and noise. You struck it, or it struck you, like a spasm,—and so you “experienced” religion.

The Congregationalists deterred me with their starchiness and self-conscious true goodness, and their desire only for high-toned affiliates.

Unitarianism seemed all doubt, doubting even itself.

A number of other Protestant sects based on some novelty or eccentricity—life Quakerism—I found not worth a serious study by the non-Christian. But on one point this mass of Protestant dissension cordially agreed, and that was in a united hatred of Catholicism, the older form of Christianity. And Catholicism returned with interest this animosity. It haughtily declared itself the only true Church, outside of which there was no salvation—for Protestants especially; that its chief prelate was the personal representative of God on earth, and that he was infallible. Here was religious unity, power, and authority with a vengeance. But, in chorus, my solicitous Protestant friends beseeched me not to touch Catholicism, declaring it was worse than my heathenism—in which I agreed; but the same line of argument also convinced me that Protestantism stood in the same category.

In fact, the more I studied Christianity in its various phases, and listened to the animadversions of one sect upon another, the more it all seemed to me “sounding brass and tinkling cymbals.”

Disgusted with sectarianism, I turned to a simple study of the “inspired Bible” for enlightenment.

The creation fable did not disturb me, nor the Eden incident; but some vague doubts did arise with the deluge and Noah’s Ark; it seemed a reflection on a just and merciful Divinity. And I was not at all satisfied of the honesty and goodness of Jacob, or his family, or their descendants, or that there was any particular merit or reason for their being the “chosen” of God, to the detriment of the rest of mankind; for they so appreciated God’s special patronage that on every occasion they ran after other gods, and had a special idolatry for the “Golden Calf,” to which some Christians allege they are still devoted. That God, failing to make something out of this stiff-necked race, concluded to send his Son to redeem a few of them, and a few of the long-neglected Gentiles, is not strikingly impressive to the heathen.

It may be flattering to the Christian to know it required the crucifixion of God to save him, and that nothing less would do; but it opens up a series of inferences that makes the idea more and more incomprehensible, and more and more inconsistent with a Will, Purpose, Wisdom, and Justice thoroughly Divine.

But when I got to the New Dispensation, with its sin-forgiving business, I figuratively “went to pieces” on Christianity. The idea that, however wicked the sinner, he had the same chance of salvation, “through the Blood of the Lamb,” as the most God-fearing—in fact, that the eleventh-hour man was entitled to the same heavenly compensation as the one who had labored in the Lord’s vineyard from the first hour—all this was absolutely preposterous. It was not just, and God is Justice.

Applying this dogma, I began to think of my own prospects on the other side of Jordan. Suppose Dennis Kearney, the California sand-lotter, should slip in and meet me there, would he not be likely to forget his heavenly songs, and howl once more: “The Chinese must go!” and organize a heavenly crusade to have me and others immediately cast out into the other place?

And then the murderers, cut-throats, and thieves whose very souls had become thoroughly impregnated with their life-long crimes—these were they to become “pure as new-born babes”—all within a few short hours of a death-preparation—while I, the good heathen (supposing the case), who had done naught but good to my fellow-heathen, who had spent most of my hard earnings regularly in feeding the hungry, and clothing the naked, and succoring the distressed, and had died of yellow fever, contracted from a deserted fellow being stricken with the disease, whom no Christian would nurse, I was unmercifully consigned to hell’s everlasting fire, simply because I had not heard of the glorious saving power of the Lord Jesus, or because the construction of my mind would not permit me to believe in the peculiar redeeming powers of Christ!

But, then it gently insinuated: “Oh, no! You heathen who had not heard of Christ will not be punished quite so severely when you die as those “who heard the gospel and believed it not.”

The more I read the Bible the more afraid I was to become a Christian. The idea of coming into daily or hourly contact with cold-blooded murderers, cut-throats, and other human scourges, who had had but a few moments of repentance before roaming around heaven, was abhorrent. And suppose, to this horde of shrewd, “civilized” criminals should be added the fanatic thugs of India, the pirates of China, the slavers, the cannibals, et al. Well, this was enough to shock and dismay any mild, decent soul not schooled in eccentric Christianity.

It is not only because I want to be honest, and to be sure of a heavenly home, that I choose to sign myself “Your Heathen,” but because I want to be as happy as I can, in order to live longer; and I believe I can live longer here by being sincere and practical in my faith.

In the first place, my faith does not teach me predestination, nor that my life is what the gods hath long foreordained, but is what I make it myself; and naturally much of this depends on the way I live.

Unlike Christianity, “our” Church is not eager for converts; but, like Free Masonry, we think our religious doctrine strong enough to attract the seekers after light and truth to offer themselves without urging, or proselytizing efforts. It pre-eminently teaches me to mind my own business, to be contented with what I have, to possess a mind that is tranquil, and a body at ease at all times,—in a word it says: “Whatsoever ye would not that others should do unto you do ye not even so unto them.” We believe that if we are not able to do anybody any good, we should do nothing at all to harm them. This is better than the restless Christian doctrine of ceaseless action. Idleness is no wrong when actions fail to bring forth fruits of merit. It is these fruitless trials of one thing and another that produce so much trouble and misery in Christian society.

If my shoe factory employs 500 men, and gives me an annual profit of $10,000, why should I substitute therein machinery by the use of which I need only 100 men, thus not only throwing 400 contented, industrious men into misery, but making myself more miserable by heavier responsibilities, with possibly less profit?

We heathen believe in the happiness of a common humanity, while the Christian’s only practical belief appears to be money-making (golden-calf worshiping); and there is more money to be made by being “in the swim” as a Christian than by being a heathen. Even a Christian preacher makes more money in one year than a heather banker in two. I do not blame them for their money-making, but for their way of making it.

How many eminent Christian preachers sincerely believe in all the Christian mysteries they preach? And yet it is policy to be apparently in earnest; in fact, some are in real earnest rather from the force of habit than otherwise;—like a Bowery auctioneer who, to make trade, provides customers too—to keep up the appearance of rushing business. The more converts made, the more profit to the church, and the more wealth in the pocket of the dominie.

How would the hundred of thousands of these Christian ministers in the United States make their living if they did not bulldoze it out of the pockets of the credulous by making the “pews” believe what the “pulpit” does not?

Nor do we heathen believe in a machine way of doing good. If we find a man starving in the streets we do not wait until we find the Overseer of the Poor, nor for the unwinding of other civilized red tape before relieving the man’s hunger. If a heathen sees a man fall from a tree-top, and seriously injure himself, he does not first run to a hospital for an ambulance, nor does the ambulance-man first want to know what precinct the injured man belongs to; but forthwith he is cared for and taken to the nearest shelter for other needed treatment, and when the danger is over then red tape may come in—the Christian machinery.

If we do anything charitable we do not advertise it like the Christian, nor do we suppress knowledge of the meritorious acts of others, to humor our vanity or gratify our spleen. An instance of this was conspicuous during the Memphis yellow-fever epidemic a few years ago, and when the Chinese were virulently persecuted all over the United States. Chinese merchants in China donated $40,000 at that time to the relief of plague-stricken Memphis, but the Christians quietly swallowed the sweet morsel without even a “thank you.” But they did advertise it, heavily and strongly, all over the world, when they paid $137,000 to the Chinese Government as petty compensation for the massacre of 23 Chinamen by civilized American Christians, and for robbing these and other poor heathen of their earthly possessions.

In matters of charity Christians invariably let their right hand know what the left is doing, and cry it out from the housetops. The heathen is too dignified for such childish vainness.

Of course, we decline to admit all the advantages of your boasted civilization; or that the white race is the only civilized one. Its civilization is borrowed, adapted, and shaped from our older form.

China has a national history of at least 4,000 years, and had a printed history 3,500 years before a European discovered the art of type-printing. In the course of our national existence our race has passed, like others, through mythology, superstition, witchcraft, established religion, to philosophical religion. We have been “blest” with at least half a dozen religions more than any other nation. None of them were rational enough to become the abiding faith of an intelligent people; but when we began to reason we succeeded in making society better and its government more protective, and our great Reasoner, Confucius, reduced our various social and religious ideas into book form, and so perpetuated them.

China, with its teeming population of 400,000,000, is demonstration enough of the satisfactory results of this religious evolution. Where else can it be paralleled?

Call us heathen, if you will, the Chinese are still superior in social administration and social order. Among 400,000,000 of Chinese there are fewer murders and robberies in a year than there are in New York State.

True, China supports a luxurious monarch—whose every whim must be gratified; yet, withal, its people are the most lightly taxed in the world, having nothing to pay but from tilled soil, rice, and salt; and yet she has not a single dollar of national debt.

Such implicit confidence have we Chinese in our heathen politicians that we leave the matter of jurisprudence entirely in their hands; and they are able to devise the best possible laws for the preservation of life, property, and happiness, without Christian demagogism, or by the cruel persecution of one class to promote the selfish interests of another; and we are so far heathenish as to no longer persecute men simply on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, but treat them all according to their individual worth.

Though we may differ from the Christian in appearance, manners, and general ideas of civilization, we do not organize into cowardly mobs under the guise of social or political reform, to plunder and murder with impunity; and we are so far advanced in our heathenism as to no longer tolerate popular feeling or religious prejudice to defeat justice or cause injustice.

We are simple enough, too, not to allow the neglect or abuse of age by youth, however mild the form. “The silent tears of age will call down the fire of heaven upon those who make them flow.”

“He who witnesseth a crime without preventing its commission or reporting the same to the nearest magistrate is equally responsible with the principal.”

“If a stronger man assaults another who is weaker, it is the duty of the passer-by to take the weak man’s part.” But to Christians this would be a spectacle merely,—one to be encouraged rather than prevented.

A heathen is not allowed to marry unless he is a good citizen, moral, and capable to instruct the children he may be honored with.

“Parents are responsible for the crimes of their children.” This is an axiom of the common law in Chinese heathendom.

We do not embrace our wives before our neighbor’s eyes, and abuse them in the privacy of home. If we wish to fool our neighbors at all about our domestic affairs we would rather reverse the exhibition—let them think we dislike our wife, while love at home would be the warmer.

I would rather marry in the heathen fashion than in the Christian mode, because in the former instance I would take a wife for life, while in the second instance it is entirely a game of chance.

We bring up our children to be our second selves in every sense of the word. The Christian’s children, like himself, are all on the lookout for No. 1, and it is a common result that the old people are badly “left” in their old age.

While traveling among the Christians one has to keep his eyes wide open; even then he has to pay dear for his comforts. In traveling in China among the pure heathen, especially in the interior, a stranger is not everybody’s cow,—only good to be milked and then turned loose,—but he is the public’s guest: his money is a secondary consideration.

As the heathen does not encourage labor-saving machinery, I do not have to be idle if I don’t want to, and, as a result, work is more equally distributed.

If a hungry heathen steals a bowl of rice and milk, and eats it on the premises,

the magistrate discharges him—as a case of necessity—like self-defense. But he who knows the law and violates it, is punished more severely than he who is ignorant of it.

Christians are continually fussing about religion; they build great churches and make long prayers; and yet there is more wickedness in the neighborhood of a single church district of one thousand people in New York than among one million heathen, churchless and unsermonized.

Christian talk is long and loud about how to be good and to act charitably. It is all charity, and no fraternity— “there, dog, take your crust and be thankful!” And is it, therefore, any wonder there is more heart-breaking and suicides in the single State of New York in a year than in all China?

The difference between the heathen and the Christian is that the heathen does good for the sake of doing good. With the Christian, what little good he does he does is for immediate honor and for future reward; he lends to the Lord and wants compound interest. In fact, the Christian is the worthy heir of his religious ancestors.

The heathen does much and says little about it; the Christian does little good, but when he does he wants it in the papers and on his tombstone.

Love men for the good they do you is a practical Christian idea, not for the good you should do them as a matter of human duty. So Christians love the heathen; yes, the heathen’s possessions; and in proportion to these the Christian’s love grows in intensity. When the English wanted the Chinamen’s gold and trade, they said they wanted “to open China for their missionaries.” And opium was the chief, in fact, only, missionary they looked after, when they forced the ports open. And this infamous Christian introduction among Chinamen has done more injury, social and moral, in China than all the humanitarian agencies of Christianity could remedy in 200 years. And on you, Christians, and on your greed of gold, we lay the burden of the crime resulting; of tens of millions of honest, useful men and women sent thereby to premature death after a short miserable life, besides the physical and moral prostration it entails even where it does not prematurely kill! And this great national curse was thrust on us at the points of Christian bayonets. And you wonder why we are heathen?

The only positive point Christians have impressed on heathenism is that they would sacrifice religion, honor, principle, as they do life, for—gold. And then they sanctimoniously tell the poor heathen: “You must save your soul by believing as we do!”

Members of my faith do not so worship gold, although they know it is a very handy thing to have in the house: but honor and principle are dearer than pelf to the average heathen. But I dare say when the heathen have become sufficiently demoralized by contact with the Christian civilization and its Vanity Fair of pretence, pride, and dress, they will probably be worse even than the Christian in beating their way through this wide, wicked world. Pupils are often too apt.

In public affairs, it is either niggardliness that puts a premium on dishonesty, or loose extravagance for show, that encourages political debauchery and jobbery. In general, business men are lauded as great financiers who actually conspire to buy laws, place judges, control senates, corner and regulate at will the price of natural products; and, in fact, act as if the whole political and social machinery should be a lever to them to operate against the interests of the nation and people. In a heathen country such conspirators against social order and the general welfare would have short shrift.

Here in New York, the richest and the poorest city in the world, misery pines while wealth arrogantly stalks. The poor have the votes, and yet elect those who betray them for lucre to corporate and capitalistic interests; and the administration of justice—in fact, the whole system of jurisprudence—is to stimulate a crime rather than prevent it. As to preventing poverty, or rendering it less intolerable, that is the most remote thought of religious and political local administration.

It is no wonder, under such circumstances and conditions, that New York is a most heavily taxed city, and the worst governed for the interests of New York. “Public office a public trust?” Rather, it is a farm to be worked, Christian-like, for all it is worth. Public spiritedness and moral worth have no value or utility in “practical” Christian politics. Such civic virtues “don’t pay.”

Do as we do. Give public office to the competent. Pay them well. If they are inefficient or indifferent, remove them at once. If dishonest, morally or financially, kill them as traitors.

“It is better that a child knows only what is right and what is wrong than to have a rote knowledge of all the books of the sages, and yet not know what is right and what is wrong.” Collegiate education does not necessarily make a youth fit for the duties of life. And men like Lincoln, Greeley, and other such Americans prove it.

“The most successful youth in life is not the most learned, but the most unblemished in conduct.” So say the heathen. But here, it is called smart when a boy is merely impudent to the old, and it is “smartness,” and is excused by the phrase that “boys will be boys” when a boy throws a stone with malice to break some one’s window, or do some injury. And parents of such a boy, while they chide, will secretly chuckle, “he’s got the makings of a man in him.”

It is our motto, “If we cannot bring up our children to think and do for us when we are old as we did for them when they were young, it is better not to rear them at all.” But the Christian style is for children to expect their parents to do all for them, and then for the children to abandon the parents as soon as possible.

On the whole, the Christian way strikes us as decidedly an unnatural one; it is every one for himself—parents and children even. Imagine my feelings, if my own son, whom I loved better than my own life, for whom I had sacrificed all my comforts and luxury, should, through some selfish motive, go to law with me to get his share prematurely of my property, and even have me declared a lunatic, or have me arrested and imprisoned, to subserve his interest or intrigue! Is this a rare Christian case? Can it be charged against heathenism?

We heathen are a God-fearing race. Aye, we believe the whole Universe-creation—whatever exists and has existed—is of God and in God; that, figuratively, the thunder is His voice and the lighting His mighty hands; that everything we do and contemplate doing is seen and known by Him; that He has created this and other worlds to effectuate beneficent, not merciless, designs, and that all that He has done is for the steady, progressive benefit of the creatures whom He endowed with life and sensibility, and to whom as a consequence He owes and gives paternal care, and will give paternal compensation and justice; yet His voice will threaten and His mighty hand chastise those who deliberately disobey His sacred laws and their duty to their fellow man.

“Do unto others as you wish they would do unto you,” or “Love your neighbor as yourself,” is the great Divine law which Christians and heathen alike hold, but which the Christians ignore.

This is what keeps me the heathen I am! And I earnestly invite the Christians of America to come to Confucius.

WONG CHIN FOO.

Citation

The North American Review, Vol. 145, No. 369 (Aug., 1887), pp. 169-179