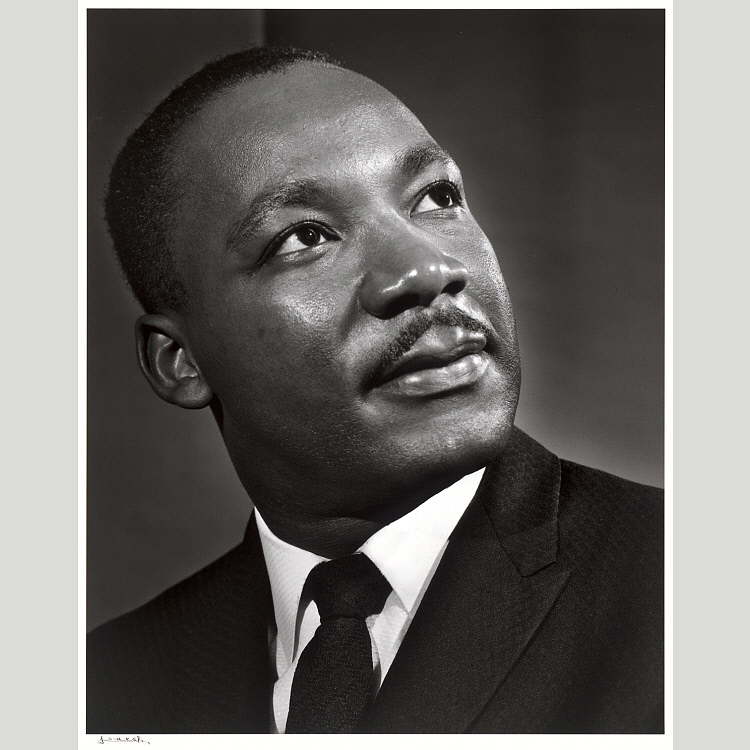

Frederick Douglass, in one of his last speeches, drew attention to a little-known book published in 1680, The Negroes’ and Indians’ Advocate, Suing for Their Admission Into the Church. Written by Rev. Morgan Godwyn, an Anglican missionary to Virginia and Barbados, the book appealed to the Archbishop of Canterbury to authorize and encourage Anglican priests to baptize enslaved persons in the English colonies of America. Douglass calls Godwyn’s book “the first publication in assertion and vindication of any right of the Negro, of which I have any knowledge.”

Douglass spoke of the book before a largely African American audience, gathered on April 16, 1883 to celebrate the twenty-first anniversary of emancipation within the District of Columbia. Douglass pulled his copy of Godwyn’s small book from a coat pocket and held it up to his audience, describing it as “the starting point, the foundation of all the grand concession yet made to the claims, the character, the manhood and the dignity of the Negro.”

Godwyn’ s Limited Petition

As Douglass points out, Godwyn did not argue for abolition – only for admission of slaves to the Christian church. Yet Douglass contends that the arguments Godwyn made for baptizing slaves pointed toward the inevitable end of slavery and toward extension of civil rights to black Americans.

During the first decades of slavery in America, most slave owners were reluctant to share the Christian faith with those they considered their property, for reasons Douglass calls “logical.” Slave owners contended that baptism

During the first decades of slavery in America, most slave owners were reluctant to share the Christian faith with those they considered their property, for reasons Douglass calls “logical.” Slave owners contended that baptism

. . . could only be properly administered to free and responsible agents, men, who, in all matters of moral conduct, could exercise the sacred right of choice; and this proposition was very easily defended. For, plainly enough, the Negro did not answer that description. The law of the land did not even know him as a person. He was simply a piece of property, an article of merchandise, marked and branded as such, and no more fitted to be admitted to the fellowship of the saints than horse, sheep or swine. . . .

Admitting slaves to the Christian faith meant admitting them as fellow children of God, made in God’s image. It implied the equality of slave and master. Indeed, by “the common law at that time, baptism was made a sufficient basis for a legal claim for emancipation,” Douglass says.

Colonial legislatures would enact laws that erased that common law understanding. Yet these legal measures to ensure the perpetual and heritable bondage of American slaves had to overcome the instinctive recognition that there was something deeply immoral about it.[1]

A Persistent Contradiction

Indeed, the recognition that slavery contradicted Christian values would soon lead to objections to slave-holding within some Christian sects. The first protest arose among pietist Lutherans and Quakers in Germantown, Pennsylvania, only eight years after Godwyn’s book was published. In the Society of Friends, what began as a protest by a small minority of the Germantown settlers would grow into a prevailing condemnation of slavery. Elsewhere, Christians opposed to slavery contended against accommodationist sentiment in the northern colonies and direct investment in the slave system in the southern ones.

As slavery took deeper hold in the south, slaveowners relented in favor of extending Christian teaching to slaves, becoming persuaded that this might induce their obedience. They relied on the ministers they supported to teach selections of scripture that could be read as supporting their authority. At the same time, many African Americans were strongly attracted to Christianity, recognizing its inherently liberating tendency. These contrasting understandings of the faith would at times “disturb the relation of master and slave,” just as, Douglass noted, slaveholders had feared they would. For example, in the Moravian community in Salem, North Carolina, slaves admitted to the Moravian fellowship claimed small freedoms to test the sincerity of those who admitted them. The Moravians responded with punishments, yet the meticulous records they kept reveal some degree of soul-searching.

Aaron Douglas, Into Bondage, 1936, American Paintings, 1900–1945, NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/artobject/166444.

Douglass calls Godwyn’s book “an ethical wonder” within its 17th century context. Indeed, Godwyn anticipates all the arguments abolitionists would later make, insisting on the slaves’ physical, moral, and intellectual equality with the European Americans who held them in bondage. Even as civil rights for black Americans were being eroded in the aftermath of Reconstruction, Douglass uses Godwyn’s example to argue that those rights must inevitably be recognized and guaranteed. “When viewed relatively, low as was the ground assumed by this good man two hundred years ago, [Godwyn] was as far in advance of his times then as Charles Sumner was when he first took his seat in the United States Senate. What baptism and church membership were for the Negro in the days of Godwin, the ballot and civil rights were for the Negro in the days of Sumner.”

[1] For a thorough discussion of colonial attitudes toward the baptizing and instruction of slaves in the Christian religion, see Albert J. Raboteau, “Cathechesis and Conversion,” Ch. 3, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South, Updated Edition (Oxford University Press, 2004), especially p. 98 – 128.