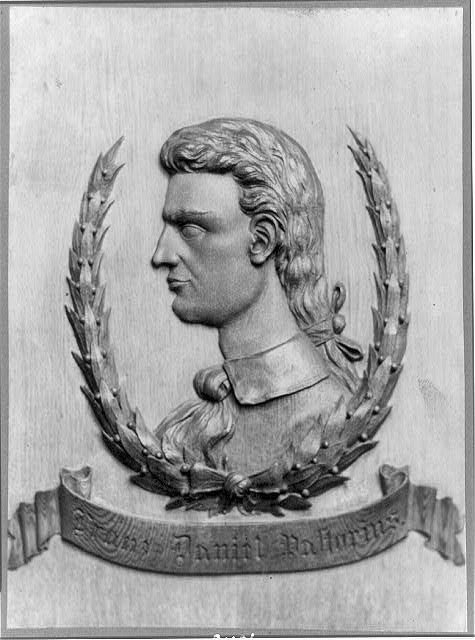

Portrait of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. Wikimedia Commons.

The Narrative of Cabeza de Vaca (first published in 1542) gives a vivid and frank account of an early and disastrous attempt to conquer and settle New World territory. The author, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, was second-in-command on a venture to settle what the Spaniards called “Florida”—the vast and as yet unexplored area north of New Spain (present-day Mexico), stretching from the Florida peninsula to the Pacific coast. Of the 600 men who sailed from Seville in June 1527 under the impetuous leadership of Pánfilo de Narváez, four alone would reach the Gulf Coast of Florida and survive a mostly overland trek to Mexico. Their voyage of conquest turned into a battle for survival among the impoverished and sometimes hostile coastal tribes. Eventually it became a cross-cultural spiritual encounter, as the three Spaniards and one North African slave learned and practiced a form of faith healing that gained them Native allies and speeded their progress across the continent.

An Explorer with a More Prudent, Less Desperate Ambition

Pánfilo de Narváez, leader of the ill-fated 1527 expedition to Florida. The Florida Memory Blog, State Library and Archives of Florida.

Cabeza de Vaca brought to the Florida expedition a less desperate ambition than his commanding officer, along with a greater ability to empathize with his subordinates and with the indigenous people he would encounter. More cautious and practical than Narváez, he early voiced his objections to his superior’s plans, but was each time overruled. After a third of the crew deserted at Santa Domingo, and another group drowned in hurricane weather off Cuba, Narváez proceeded to the vicinity of present-day Tampa Bay and ordered Cabeza de Vaca to lead a large reconnoitering force ashore—while he, Narváez, continued to sail up the coast toward some unspecified meeting point.

“Upset in the Surf,” an illustration of the event that ended the Narvaez expedition and began Cabeza de Vaca’s long journey across the Gulf Coast of North America: the wreck of the rafts near Galveston Island. From A Popular HIstory of the United States by William Cullen Bryant and Sydney Howard (Scribner, Armstrong, and Company, 1876). Wikimedia Commons.

As Cabeza de Vaca feared, the land-going party would never rejoin Narváez, who perished with his men during a storm in the Gulf. The log-choked bayous and arrow-wielding natives of Florida’s west coast prevented any conquest of territory there. Abandoning that plan, Cabeza de Vaca and his men built rafts, hoping to sail them across the Gulf to Spanish-settled Mexico. They drastically underestimated the distance they had to cross, and were shipwrecked near present-day Galveston when their feeble craft encountered the powerful current created by the Mississippi.

A Long Overland Walk Through Native American Communities

Cabeza de Vaca’s slow overland odyssey began then, in late 1528. The small group of shipwreck survivors would be rescued from exposure and starvation by sympathetic natives, then forced to work for them, harvesting the roots that supplied their meager diet. After most died, and a few escaped to live among other nearby tribes, Cabeza de Vaca spent four years as the sole Spaniard among indigenous people of varying customs and languages, repeatedly negotiating the terms of his survival. As he escaped one coastal tribe to join another, he shared their poverty, learned some of their languages, and observed family patterns and belief systems he would later record in his narrative.

“Expedition des Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca 1528 bis 1536,” a map reconstructing Cabeza de Vaca’s journey by sea and overland through the Gulf and southwestern regions of North America, created by the German cartographer “Lencer” in January 2008. Wikimedia Commons.

In the spring of 1533, he encountered three other survivors—two Spaniards and Estevanico, the slave who had been brought as a servant on the Florida expedition (and who would later play a brief and colorful role in Spanish efforts to extend their settlement into the area of present-day New Mexico)—and with them devised a plan to travel westward overland, in hopes of reaching Spanish settlers in New Spain.

Accepting the Role of Faith Healer

Their movement among tribes was aided by the natives’ discovery that the four men possessed the power to heal their sick. Perhaps the novelty of their appearance, or perhaps their survival through disasters and periods of starvation (a seasonal hardship for natives who did not practice agriculture), suggested that they possessed unusual powers. At the natives’ insistence, Cabeza de Vaca and his traveling companions began using a native folk cure involving breathing over the sick. Combining the practice with Christian prayer, they restored hundreds of the sick to health.

An illustration from the Florentine Codex, an ethno-history of the Aztec people written by 16th-century Spanish Franciscan missionary Bernardino de Sahagún, showing Aztecs infected by smallpox. Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence.

It seems likely their success as healers was enabled by faith on both sides, that of the healer and the healed. Cabeza de Vaca repeatedly attributes to divine grace his own survival of repeated privations and ordeals, and it is believable that he felt sustained by continual prayer. As for the healed, the narrative recounts that as the four travelers entered the Southwest, where food was more plentiful because of the agricultural practices of many indigenous tribes, they were treated less as servants and more as honored guests, priests with an increasing celebrity status. [Certainly the latter part of the author’s remarkable journey at times recalls the lives of the early Christians as recounted in the Book of Acts, since Cabeza de Vaca and his companions maintain a kind of communal fraternity with those they heal, refusing most of the gifts they are offered.

They began moving from village to village with large native escorts who, after introducing them as powerful healers, seized the village’s goods as recompense for having brought them assurance of health. The dispossessed villagers then took the place of the escort party who had brought them the healers, making the same requirement of the next village.

A Troubled Reunion with Fellow Spaniards

Eventually Cabeza de Vaca and his companions reached areas showing signs of sudden abandonment by the inhabitants. They would learn the cause when they at last encountered a party of Spanish slave-catchers, whose immediate impulse was to enslave their lost countrymen’s new native friends.

Protesting this, Cabeza de Vaca won the slavers’ apparent agreement to allow the natives to return to their homes, but soon found they meant to go back on their promise after separating him from his native friends. Cabeza de Vaca recounts that this plan was overruled by Melchior Díaz (the chief civil authority in this northernmost province of New Spain) and that the natives of the area afterwards agreed to convert to Christianity and cooperate with Spanish rule. This positive conclusion of the eight-year adventure probably simplified the reality, but it helped the author make the point he wished to convey to the Spanish King and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, the audience to whom he addresses his story. Spanish settlement of the new world will more likely prosper if the natives are treated with respect and kindness, he insists.